"A man or a mother": the women and invasions of Florida's most profound lawsuit

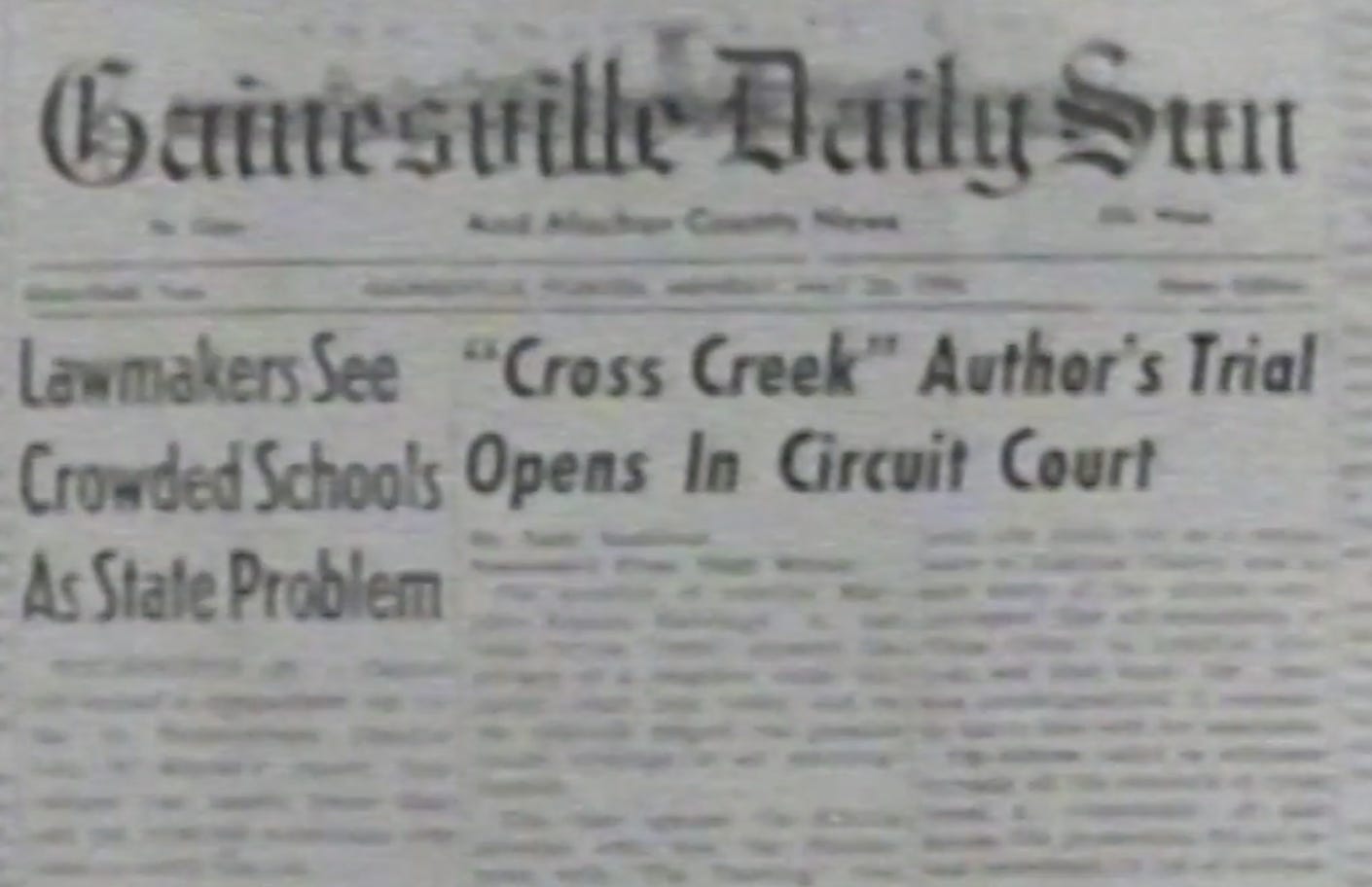

A fun, dramatized excerpt from my book-in-progress about the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings invasion of privacy lawsuit and World War II Florida.

In 1942, a woman named Zelma Cason sued iconic Florida writer Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings over how Marjorie portrayed her, using her real first name, in the book Cross Creek. Zelma alleged libel and invasion of privacy. My great aunt Kate Walton and great grandfather Judge Vertrees (J.V.) Walton represented Zelma.

Every quoted word in what you’re about to read comes directly, verbatim, from the official transcript of Cross Creek invasion of privacy trial held in Gainesville in 1946. According to the court reporter, each character spoke those exact phrases.

The written representation of unspoken thoughts and feelings, by contrast, are my creations. They come from my research, extrapolation, and imagination. I am responsible for their accuracies and their errors, which you probably can’t prove or disprove anyway.

But you should know that a much older Kate Walton played a profound role in my life that had nothing to do with lawyering. To a 6-year-old boy, she was the Aunt Katie who spent every Saturday morning showering me with the type of girding love that every child deserves. I snatched my first fish from the St. Johns River with her help from her dock with her cane pole. We roamed her then-wild riverfront property in a golf cart that she taught me to drive. My first experience with grief was her death when I was 14. And I wrote my first serious essay about it when I was 17.

I carry all of that into the courtroom with a Kate Walton I did not know but have repeatedly recognized within myself as I’ve studied her. If you think I can possibly be disloyal to her, you are mistaken. But loyalty and honesty need not be at war.

May 24, 1946, Gainesville, Florida

“I ask you to turn to Chapter 5, to the characterization that you say was written in 1941, and interpret it as it was written in your mind and heart.”

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Baskin started to answer her lawyer: “I had to stop and think — how do you describe Zelma…”

Kate Walton interrupted. “Object to the question,” said the 33-year-old co-counsel for the plaintiff. She remained seated; but her voice commanded the room to her.

“A written instrument is its own best evidence as to what she meant or intended. If she uses words she is presumed to intend a reasonable meaning of those words, and to vary the terms of that description by her own testimony would not be proper.”

Kate Walton had written millions of words in preparation and litigation; and millions more were still to come. But those were the only 50 she would ever say in Marjorie Rawlings’ direction during the Cross Creek invasion of privacy trial.

Circuit Judge John Murphree waved them away with casual economy. “Objection overruled.”

Marjorie continued: “As I said, I had to sit down and think, now how do you describe Zelma? What is she?”

***

Marjorie still couldn’t believe she was here, in a Gainesville courtroom, explaining and defending her work as a Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicler of rural North Florida. Under oath and pain of perjury. Cross-examined by that short, pot-bellied, fake cracker aristocrat J.V. Walton, who wore a goddamn pith helmet to court.

Her love for Zelma Cason interrogated — in front of all their friends and acquaintances.

No other major American writer of 20th century ever endured such a thing.

“So help me God,” she had sworn, little hand raised, half-choking on incredulity with a composed smile.

(Still image of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings on the stand from film footage of the trial)

All this fuss and disruption and suffering because of four stupid sentences – and one stray word. It was an unnecessary chapter, depicting a 16-year-old scene: a Census ride in the cracker backwoods around Gainesville in 1930. A little nest of “pickaninnies”, a smattering of mud-stained crackers. Lots of trees. And horses. That was it, really. Dear God. If only Max Perkins hadn’t liked it; she might have cut it.

Zelma is an ageless spinster resembling an angry and efficient canary. She manages her orange grove and as much of the village and country as needs management or will submit to it. I cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother. She combines the more violent characteristics of both and those who ask for or accept her manifold ministrations think nothing of being cursed loudly at the very instant of being tenderly fed, clothed, nursed or guided though their troubles.

Was that really so awful? Life-changing? Damaging?

Of course not: it’s loving, affectionate. Sisterly. Yes, she also called Zelma “profane” in the chapter. Because Zelma was profane. Is profane. She would cuss a minister in prayer, as everyone sitting here knew. Including Zelma. Writers are in the business of truth. And Marjorie was a writer, before anything else. Before she was a citrus grower, a hostess, or even a wife.

All Gainesville had gathered to watch lawyers examine and cross examine the existence of Zelma Cason’s cursing. They might as well cross examine gravity. Marjorie laughed at the absurdity. It helped to fight the endless churn in her gut. Petulant Zelma. She knows how sick she has made me. It pleases her. Petulant Zelma. Profane Zelma.

Marjorie took great pleasure in how Judge Murphree flicked away the snarling little Walton daughter’s outburst. Kate would, indeed, cross examine gravity, if given the chance. And Marjorie thought she sensed an allied annoyance from the affable judge. You can only be badgered and appealed so many times as a judge before your humanity takes over.

It had occurred to Marjorie over the course of litigation and trial that Kate Walton looked on her like Marjorie looked on her own wretched mother. As if I deserve that —from you, dear girl, who wants to be me. I’ve done what you can only imagine. And you would punish me for it. And when you’ve ruined me, who else will you look to, with that sharp childish mind of yours? Who else will show you the possibilities of a life beyond Daddy? You own mother?

Marjorie’s father did not plant Marjorie’s oranges — or purchase and publish her words. And now, this entitled girl wanted to confiscate that accomplishment. Indeed, she sought to call it illegal, fraudulently earned — an invasion of privacy. Whatever the hell that meant.

Imagine Hemingway, under oath, answering for his Scott Fitzgerald cruelties. No man would sue another man for this. No man would ever have to answer for the truth told about another. And the truth Marjorie wrote about Zelma was a love letter, not a cruelty.

***

Kate knew the trial was lost long before Marjorie ever took the stand. It had become a contest of likability – of whom the assembled most enjoyed. A giggling ratification of power and celebrity. Seething at the plaintiff’s table, she had been crafting the appeal in her head since Judge Murphree let Marjorie’s lawyer bore into Zelma’s personality.

Craft the appeal was all Kate could do. Even in a case brought, prepared, and bled for on both sides mostly by women, concerning what it meant to be a woman, a lady lawyer operating in front of an all-male Florida jury dared question only ladies deemed incidental to the case.

Indeed, the newspaper writers that swarmed Gainesville for the trial hardly noticed Kate Walton at all. As the Miami Herald put it:

“Some of the principal characters in the legal battle are as colorful as are those of whom they argue. Both J.V. Walton of Palatka, who is the leading ball carrier for Miss Cason and Phillip May of Jacksonville, head of the defense staff, are small fellows physically but not mentally.

“Walton’s mannerisms are as back country as a dish of collard greens, grits, and side meat. But so have been the mannerisms of some very smart attorneys – the great Clarence Darrow among them…

“Walton’s associates are his daughter Kate, a law graduate from Florida, and A.E. Clayton, of Gainesville.”

Kate’s objection shocked the gallery like someone dropping a heavy book. And it had earned the rare sharp glance from her father. She was willing to bear it. Impotent silence hurt that much.

As Kate was tallying Murphree’s errors of law, J.V. Walton’s cross-examination of Marjorie devolved into Socratic vaudeville, much to the delight of most everyone not at the plaintiff’s table.

It reached crescendo as J.V. interrogated how Rawlings told the story in Cross Creek of her brother’s armed assault on the living quarters of her black maid and her handyman lover.

Kate Walton knew what it was like, as did her father, to have armed men wrapped in power invade the sovereignty of home in the middle of the night. She did not know what it felt like to simply endure it, without recourse, as Marjorie’s negro employees did. It’s why the Black Shadows chapter of Cross Creek drove the moral energy of J.V.’s questioning.

Didn’t Marjorie think it was “improper” for her brother to storm into the tenant house in the middle of the night to roust the sleeping workers for their partying?

Yes, but…,Marjorie answered, and then she asked a question of her own.

“May I inquire what is the law when you own the tenant house on your own property and the negroes are working for you and you pay them their weekly wages and they pay no rent on the house?” Marjorie asked.

J.V. Walton answered first: “And you provide them the house to live in?”

“Yes. I mean what is the law?”

“I would say the law is –.”

Marjorie’s lawyer, Phil May, interrupted him: “Your honor please, I think this has gone too far and it is obviously argument and I object.”

Kate knew what her father was going to say before he said it. And she registered her own silent objection. Don’t do it, Daddy. They’re laughing at you, not her. They’re laughing at us. At our client. At her powerlessness.

“It is the witness’ question he is objecting to,” Walton retorted, with a twinkling exasperation. The laughter of the crowd grew.

Murphree picked up the routine in perfect time. “I think we have this backward.”

The laughter broke like a wave in the distance, indelible in Kate’s hippocampus for the rest of her life.

That the father Kate revered more than any other person had worked Murphree into the bit and played along … well, some things you don’t ever reckon with. But J.V. Walton, as a father, had earned the right to unwittingly trivialize his daughter’s ideas and case at trial without open consequence between them. History and record and love matters. Kate focused on the judge instead.

Twenty years earlier, in 1926, Kate and J.V. had endured and confronted mortal danger together, as father and daughter, in protection of their home. Now they endured humiliation together, as father and daughter. That a judge would participate in it, especially this judge with this name, enraged her.

Go ahead and laugh, you damn son of a coward. Make a mockery of law like your father did. I will tear your errors limb from limb. Just like I did before, when you thought we weren’t entitled to a trial. Wait until it’s just you and me – and the law. And ask Max Perkins how it feels to have me question you without a laughing mob to back you up.

***

Judge Murphree reveled in his timing.

“I think we have this backwards” was a pretty obvious line, if one followed the mangled structure of the cross-examination; but the judge delivered it in sublime rhythm.

Everybody laughed. The crowd laughed. Marjorie laughed. Even the elder Walton laughed.

Good humor was John Murphree’s reputation. And this trial was nothing if not funny. In the earliest moments of his career as a judge, fortune had delivered Murphree a countrified Thurber story to oversee. He doubted he would ever top it; and he couldn’t resist writing himself into it.

Yes, the judge had punch-lined a cross-examination going badly for the plaintiffs; and maybe the judicial canon or the Supreme Court would frown on that from the distance of a transcript. That notion did flash through the mirth. It tempered his expression into a slight, wry grin.

But honestly, the stakes of this case were so low; and the entertainment value so high. A moment of judicial indulgence seemed not just forgivable, but somehow appropriate. Indulgence defined this entire exercise.

It was all so high-mindedly academic in abstraction; and so hilariously petty in person. Nobody had died. Nobody would die. The war was over. The power of American good humor and law had redeemed the millions of pounds of flesh that melted into the sacred earth of Europe and the East and the depths of Pearl Harbor.

The entire Cross Creek case embodied the spoils of victory for Murphree. It was everything that was right about the American way of life he had been taught to revere. Here was the post-war world. The best women that America and Florida can offer bickering and gawking and fighting, consuming energy and resources and time because triumphant American freedom allowed it.

Indeed, everywhere he looked from the throne of the bench, Murphree saw women. He had never seen so many in one place at one time — except maybe one of his law speeches to the Women’s Club. But that didn’t really count.

Grand dames of university society commanded the front row. Their mother-of-the-bride dresses shone like bunting on a baseball grandstand. Most of them had known and revered Judge Murphree’s late lamented father, Arthur Murphree, the president who built the University of Florida into a true university.

Most had read Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ books, in which she served as a personal tour guide into the comedy and poignancy of the backwoods that sprawled around the learned oasis of their majestic university homes. When they visited her Cross Creek house, black servants cooked and fussed over them while Marjorie talked national politics and literature — not country living.

Pretty college girls — or young wives — sat clustered behind the countesses, or on the window sills radiating curiosity and possibility. Some jabbed at notebooks dutifully.

(Image from video footage of the trial)

But they did not matter to the outcome as much as the country neighbors who filled out the humanity of the gallery. And they were laughing and spitting their way through the show. They were rooting for their pal Marjorie.

As the laughter from Murphree’s successful joke subsided, Marjorie started again, in her best humble hostess voice.

“May I inquire of your Honor, I ask in all sincerity what is the law in a case like this?”

Murphree answered by beckoning to J.V. Walton: “Maybe you would like to finish one subject.”

“I don’t mind stopping if your Honor wants to answer that question.”

“Suppose you answer it,” Murphree responded.

“My conception of the law is that when people are furnished a house to live in that house becomes their castle,” J.V. said, and then returned to questioning Marjorie. “Did you consider the negroes at all?”

“I did, as I wrote,” Marjorie answered, “but my brother simply became unduly alarmed for me and was protecting what he thought was the very life of his sister.”

Murphree agreed that Marjorie needed no protection, except maybe from Kate Walton. And he found that a small shame. He genuinely enjoyed the inscrutable machinations of all these brilliant and vindictive women. So much alike. They should like each other, work in clubs and churches together. Imagine what they could do, together, to advance the lives of the people in Marjorie’s books in this world so full of American promise. He wondered, with a flush of sentimentality, what his father would think of all this.

Kate Walton erased all that with her eyes.

They bore into Murphree from atop hands folded as if in prayer, pressed with strain into her lips and the bottom of her nose. He looked away quickly. No woman had ever stared at him with open loathing before, as if she planned to do something about it, promptly, perhaps violently.

This was new. And unsettling. Maybe this was also the post war world.