"Bully": How we bury childhood suffering beneath an impossible act of administration

This is the latest installment of my "Education and the English Language" series. Previous essays are:

Introducing "Education and the English Language," a periodic series. I explain how George Orwell's famous "Politics and the English Language" essay anticipates beautifully modern political education's vapid use and outright abuse of language. I focus on "Failure Factories" as an example.

"Union": the only positive force in Florida education's human capital management model. This examines the the toxic human capital culture of DoE as an employer. "Twenty years of abusing the word “union” and anyone attached to it has produced nothing but a massive teacher shortage and the complete failure shown again by this map."

Today, we're looking at "bully."

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When I was in 8th grade, all of my best school friends simultaneously -- and pretty brutally -- turned on me. I do not remember a trigger. I do remember the mechanism. They named me "Cow" and Mooed at me somewhat relentlessly for weeks in encircling mobs within public school common spaces. For the most part, to my regret, I just took it. Adults either didn't notice or ignored it. And I made no effort to tell any adults about it. I do not remember a single moment of mercy or support from anyone -- boy or girl -- in my extended friend group once this was set in motion. That is the power of a childhood mob.

I was a little doughy, like I have always been. More or less like I am today. But I was also a good athlete. I had just started at quarterback in the All-Star game for a citywide flag football league that all my friends also played in. I was a good basketball player. I stuttered, of course, but no one seemed to seize on that. I was smart and generally popular. Girls liked me to some extent. My school years were generally happy other than this period. So I can't explain rationally why this happened. And yet it did. Something about me in that moment communicated vulnerability. And other vulnerable people -- because all middle schoolers are vulnerable -- heard it and acted on it.

Indeed, it pains me to say, in at least one case, I had physically humiliated one of the friends who turned on me. I was bigger and stronger than him at the time (that didn't last); and I embarrassed him in the guise of "playing around" after lunch one day. I remember it with clarity and shame. So from his point-of-view, even though he wasn't a leader of what happened to me, I have no doubt he thought I had it coming. All actions have consequences, especially acts of humiliation.

I have always tended toward outward stoicism about my internal pains, particularly as a child. I do not like to communicate or admit weakness or unhappiness to anyone, especially to people who care about me, like parents, who might be pained by it in turn. I can only speak with certainty for myself; but I think a lot of kids are like this. [I have a video clip about this below.]

So I didn't tell anybody anything about what has happening for quite a while. My mother, I think, had figured something was up by my moping at home. And eventually, after a city league basketball game, I blew up in front of her and a bunch of other people when one of my former best friends started chatting with my parents as if nothing had been going on.

Very shortly after that, a kindly guidance counselor called me into her office and made me tell her what was happening. I think my mom put her up to it to avoid forcing me to confess it to my parents. But I don't know for certain. I do know that I was grateful. It was an enormous relief to have someone take an interest. This kind of childhood mass cruelty is compounded by loneliness. When you're not suffering, you're alone with fresh memories of it. You're radioactive, because no one wants it done to them. That's why so many bullied kids turn around and bully somebody else. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote once: A boot on the neck is never an enobling experience. Most kids, myself included, would do anything to get it off.

I don't know what the guidance counselor did after our meeting. But my life got better. I had actually begun to find new friends already. I'm reasonably practical that way; and I did not like loneliness and suffering. I was fighting my way out of it on my own. But the adult connection helped. And eventually, the organized cruelty just sort of passed, like a plague burning itself out.

Before the end of the year, most of the people who took part were my close friends again. They remained my close friends throughout our high school years. Indeed, many remain my close friends today. They are "good people," in the same way that I was when I humiliated one of them. Only one of them, I would say, has a truly nasty, cruel streak embedded in his fundamental character. I haven't seen or talked to him in years. I think that streak has eaten his life.

Several of them hold very important positions of authority. If you look at them by social profile, they would be the same people -- just like I was for a long time -- opting out of traditional public schools because of what they fear will happen if they mix with the wrong kids.

We have never talked about this episode. Ever. None of us. Nor would I want to. I suspect, without knowing, that they remember this with some shame, just like I remember with some shame what the 8th grade asshole in me did to one of them. Shame can be very constructive and very quieting. I recommend it to a point.

Like any extreme life experience, this one stayed with me. But remembering a thing is not the same as dwelling on it or indulging it. It doesn't pain me. It's useful to me because I have not suffered much in my life. This period of suffering gave me a life-long window for empathy. Indeed, I'm telling this story precisely because it has a happy ending: my life. And I hope it can be helpful to other kids and parents.

But consider this: just a few weeks ago, a troubled troll from my hometown, who I barely know and who wasn't even part of this episode, made some reference to it on Facebook. In fact, I think he even said "Moo." I blocked him in like 3 seconds. I'll let you guess his politics and presidential vote. Indeed, I think that was the point -- the reason that an addled adult would try to use childhood cruelty as a weapon of abuse 30-plus years after it happened. I suspect if I took the the time to know what's addling him, I would find it driven by some deep cruelty visited upon him as a child. Mark Zuckerberg exploits all that for money. And he has much to answer for as a human being. The day I no longer need his platform to communicate with you as public official, I am gone from it.

Speaking of people exploiting childhood cruelty for money...

The experiences we file under the bland heading of "bully" are much on my mind these days -- as are the experiences we file under "violence" and "harassment" and "school climate" and "discipline" and "behavior." They all run together.

One reason, of course, relates to our enemies in Tallahassee running with their bully vouchers.

Bully vouchers are an intellectually and morally bankrupt idea pushed by an intellectually and morally bankrupt group of people. So of course, Rep. Colleen Burton, R-Lakeland voted for it last week as part of the awful House Bill 7055. (Sam Killebrew, R-Winter Haven, did not, interestingly enough. Thanks, Sam, I noticed.)

This is what you do when you've run out of creative ways to hurt people and public schools. You turn to stupid ways. It's what you do when you have nothing to offer anyone as a legislator except your own personal enrichment or gratification.

So I don't fear those vouchers much. I think they will have very little impact here beyond another annoying, unfunded administrative task heaped on understaffed schools. Polk County is already "vouchered" to the edge of existence by conversion charter and magnet schools. We just don't call them vouchers.

And bullied kids don't generally want to change schools. They want the suffering to stop. It never occurred to me when I was suffering to leave my school. I wanted my friends to stop hurting me. I wanted my friends back. The institutional "solution" to bullying is adults with the time and mandate to intervene productively on behalf of a suffering child -- where that child is.

The bully voucher brigade knows this. They don't care. If they cared, they would be working with us to fund school culture and intervention teams. They would be paying for counselors who can actually help a child the way a counselor helped me. Between starving your schools of money and turning your guidance counselors into test co-ordinators, your legislators have done everything they can to expose your child to cruelty and loneliness. That our understaffed teachers, administrators, and paras -- and the kids they serve -- manage to keep bullying to something of a minimum says a lot about them.

Our awful legislators do care about voucher money; and they care about associating bullying/suffering with traditional public schools in public statements. It helps them market the charter and private schools that pay them.

And consider this: a prominent private school in Polk County, within the last couple years, produced an extended bullying incident that culminated in a terrifying and public act of self-harm. No media ever reported it; and I'm not aware of any child prosecuted over what happened. But I did hear an account from a parent whose very young child -- who had nothing to do with it -- happened to be present for the act of self-harm. And as a School Board member, I see the expulsion-level discipline reports of all publicly-funded schools, charters included. Yes, they have them. Some are quite awful.

There is no place to hide from humans. There never has been.

When generations bully

Observation and interaction tells me that, taken as a whole, this generation of young people are much better humans overall than the adults that have indifferently broken their world and future. Endless social measures show they are more responsible as a group than their parents. They are more understanding of each other's differences than any prior generation that I can see. And they work very hard just to get by in a world economically hostile to them.

And yet, American culture of all political persuasions has much invested in lying about our kids as a group. American culture also has much invested in lying about -- or willfully ignoring -- the childhood behavior of the people who are now adults. It may be the only way we can live with ourselves. We adults don't do self-criticism or self-knowledge.

Our sexual-harassing, morally dead legislators are living proof of that. If our kids suck, it's easy to justify hurting or ignoring them for their own good. That's been Kelli Stargel's approach to public policy for her entire career. It's Richard Corcoran's approach today.

Of course, we adults have always complained about kids-these-days. And we've always lied to ourselves about our superior youthful virtue. It's a human tradition. As is bullying and human cruelty.

But there is something new happening today, I think. Society is creating administrative expectations and consequences for cruelty that have never existed before. Too often, these expectations are rigid and shallow. They are created with little meaningful thought to the human cost and difficulty of acting on them.

In the past, I think most boy victims of abuse or cruelty were expected to to endure quietly -- or drill somebody in the face. Most girl victims were expected just to endure quietly. Adults existed to comfort and support as the child endured the cruelty. I don't know if that's good or bad; but I do think it's been the social template of my lifetime. I suspect it was that way primarily because it was easier for adults; and adult needs always drive institutional behavior absent a greater power pushing from the outside.

Today, just such an outside power is changing this template rapidly. Social media, the fetishization of the word "bully," and the cultural earthquake of #metoo are ending the comfortable silence around the childhood suffering -- and sexualized adult suffering -- that has always existed. The profundity of the shift renders any moral judgement of it ridiculously irrelevant. Is it good or bad? Yes.

I do see two indisputable conclusions:

It has become risky for adults in institutions, especially schools, to behave with humanity toward suffering kids. It will keep getting administratively harder to behave humanely. Big Education, in the way that only Big Education can, has drained the visceral human experience of powerlessness and suffering from "bully" and left behind a cold husk of policy checklists and measurements. Today, when a child reports "bullying," a school leader has every incentive -- positive and negative -- to see an act of administration rather than a human being in pain. It's the only way to protect themselves. That's a sad, predictable irony of the focus on the word "bully."

Once again, we see that today's generation of kids may be the unluckiest in American history. They get to live through this shift, in which guilty adults are declaring in so many ways: if you dare do any of the same shit we did, act on any of the same human compulsions that all previous generations have, we will wreck you. We have zero tolerance for any emulation of us. Because we care so much about you and want to save you from suffering. I hope to spend the rest of my life fighting the fundamental, brutal cruelty of that inter-generational bullying. I don't expect to win very often.

Right in front of our popular culture noses

Children (or adults) who bully cause pain to other children or adults for a simple reason: they can.

The psychological motivations and triggers for it are endless; but the power reason is singular and timeless. Bullying delineates power in a relationship -- who suffers in an interaction and who does not. In this moment, I am stronger than you. I want you, and everyone else, to know it. I will demonstrate this by making you suffer. That's the heart of all bullying, I think. It rests on the human reality that power, in all its forms, feels better than weakness, in all its forms. Power protects you from predators. Power can ease the pain of your own weakness.

In most cases, I think, bullying isn't even personal -- although it is experienced more personally than almost anything. The power of power is deeply, deeply wired in the human condition. We can thank God or nature for it.

It is so wired that our art -- high and low -- has addressed it forever. Let's take a walk together, fellow GenXers, through the pop culture representations of our own bullying -- and that of our parents.

Start with The Brady Bunch, an episode called "A fistful of reasons."

This episode debuted in 1970, the year before I was born. The children here are roughly 5th grade age. Today, they are in their late 50s. They're thinking about retirement and perhaps lamenting the kids these days on Facebook and all the bullying that didn't exist back when they did it. Such were the good ole days. And yet, who exactly populates that suburban white swarm of bloodlusty trash-talking kids? Give them a phone and Snapchat and take away the sanitized TV lens of the creator of Gilligan's Island; and it's all the same. So much evidence of bad parenting by the Greatest Generation.

Unfortunately, violence can work against bullying. It would be a lie to say it can't. But it can also go terribly, terribly wrong. I've never seen or participated in a fight that looked like that at any age. The real violence I've participated in, seen firsthand, or found myself amid is terrifying, dangerous, and non-edifying for everyone touched by it, even if it's necessary. The click you hear when a fist cleanly strikes a facial bone is one of the worst sounds any of us is likely to hear outside of war and pestilence. It's not like the movies.

That's the dangerous aspect of this scene. I've never seen violence so contained, conclusive, and orderly as the Brady fight. Violent self-defense is always a real risk on multiple levels -- even when it's a necessary risk. And sometimes it is a necessary risk, unless you are a person of superhuman capacity to suffer for principle. Believe me when I say, today, that I wish I would have summoned the courage and rage to break one of my friends' noses all those years ago. Unless, of course, it went awry and somehow ruined my later life possibilities.

Finally, this scene happens on school grounds. Where are the rushing administrators? Where are the adults? The wholesome popular culture of the late 60s contextualized school bullying and violence as essentially private matters between kids. It did this at essentially the same time that national leader after national leader was being publicly murdered, and thousands of young men, including my father, were killing and dying in Vietnam.

A few years later, in 1974, Judy Blume wrote Blubber, which I read circa 1982 as a fifth grade boy. It's much more visceral and real than The Brady Bunch. It was like a sneak preview for my experience. Some excerpts:

We made Linda say, I am Blubber, the smelly whale of class 206. We made her say it before she could use the toilet in the Girls' Room, before she could get a drink at the fountain, before she ate her lunch and before she got on the bus to go home. It was easy to get her to do it. I think she would have done anything we said. There are some people who just make you want to see how far you can go.

-----

After I read the note I said, "Ha ha..." remembering that my mother told me a person should always be able to laugh at herself. I tried to laugh as hard as the rest of the kids to show what a good sport I could be.

"Goo goo..." Robby Winters said. "See Baby Brenner laugh!"

-------

That afternoon, when I got on the bus, Wendy stuck out her foot and tripped me. I fell flat on my face and my books flew all over the place. I tried to laugh again but this time the laugh just wouldn't come.

Blubber is a horror story, an unflinching portrait of nightmarish childhood cruelty. Its characters were conjured from real-life waking nightmares. I recognize them. Today, the flesh and blood versions of those waking nightmares are in their mid-50s. They command the institutions of the country, from an age bracket point-of-view.

And then there's this from 1985, from The Breakfast Club, the best scene John Hughes ever wrote and the only one that really holds up years on. (Good lord, Sixteen Candles is unwatchable today in every way. Loved it when I was 12.) Note the generational expectations of cruelty -- and the regret. "The fucking humiliation." The Estevez character is 51 or so now. His dad is 80ish.

No previous generation has ever attempted what society is demanding now

In the last few weeks, I've heard several actual "bully" stories from Polk parents that cover a range of ground -- sexual, sectarian, and just simple child-to-child cruelty and conflict. All of them have been made public through social media; and I've followed up to speak with parents and anyone I can to improve matters. I pride myself on my ability to fix things with reasonable solutions. If we do this, this, and this, we'll get this. And we'll all be happier.

But I haven't been able to "fix" these problems, nor have the schools in question, really. Indeed, I see no comprehensive fix for the human suffering contained within the word "bullying." Today, the emerging societal expectation that one does exist poses perhaps the most vexing internal challenge for any educational organization. That's what has made "bullying" a measurable act of administration -- a nameable, countable thing.

And now #metoo is driving an unprecedented level of focus -- and potential consequences -- on the exploited imbalances of power that have always existed. The human beings of our modern educational institutions are doomed to fail at managing these intense and conflicting pressures -- which bear on all the other pressures society and government inflicts on them.

But previous generations didn't even try.

For better or worse, that option no longer exists for the adults of our schools today. With that in mind, here are some humble suggestions/observations for the adults in our schools charged with addressing all the flawed humanity that rolls up into the string of letters that spells "bully."

In some cases, they are probably contrary to policy. But policy is often stupid and blunt. I'm talking here about personal demeanor, language, approach. The checklist is going to be the checklist. You have to do it. But within that checklist, consider these ideas.

Replace "bully" with "suffering child" in your mental vocabulary. A child reporting "bullying" is actually reporting their own suffering. Assume they are telling the truth; and act on that first. Assure the child that the adults of the school care. Tell that child: you are not alone. Loneliness may be easier to ameliorate than a toxic relationship. Easing the loneliness mattered tremendously to me in my experience.

Decouple consequences for the bully from comfort for the bullied. This relates to the first. In my conversations with parents -- and through other observations -- I think adults in authority who receive a bully report tend to move immediately to a kind of administrative equation. If X suffering exists, Y consequences must follow. Which creates new suffering and potential life destruction for the bully. It's understandable to move instantly to that equation; but it undermines efforts to comfort the suffering child. Where possible, focus immediate attention on the suffering child; come around to consequences more deliberately. Never, ever give the reporting kid the responsibility for choosing what happens to the alleged bully.

Purge "why didn't you come forward sooner" from your repertoire of questions, unless you can do it with great, great care and context. I never came forward about my experience at all. An adult came to me. There are many many reasons why kids are slow to report. Most are legitimate human reasons. Any child who admits and reports suffering at the hands of someone else is taking a personal risk. Even a delayed report is an act of courage. Treat it that way immediately. Even if you think it's false. The investigation can be cold and deliberate. But the first exchange around the report should be loving and comforting.

Listen sympathetically and non-judgmentally to parents. You gonna have your mama fight your battles for you? is a resonant taunt. All parents risk that exposure for their kids by intervening in their lives. There are times when it is absolutely a necessary risk. But there is no rubric for saying when. It differs from child to child and parent to parent. Like my own parents, my wife and I are probably on the less-intrusive scale. But that's just us. And even so, we've intervened assertively before.

I think many administrators, who see childhood cruelty all the time, understandably get a bit hardened by it. I think they tend to believe that intervening parents often do their children a disservice. And they are not wrong about that in all cases. They also know how hard it is to satisfactorily address it. So self-interest comes into play.

This is especially fraught with the public dimension of social media, which most administrators I know fear and despise. The irony of social media is now that everything is public; nothing really is. Even well-read exposes of cruelty tend to drift away like smoke without much effect on the institution. But if we listen honestly, they can often reveal problems that we should address on their own merits -- not because a bunch of people like or comment on an angry post.

I would urge administrators to fight the instinct to judge the approach a parent is taking when listening to those parents describe their children's suffering. About the only success I think I had in talking to the parents about these incidents was in giving them a sympathetic human ear. I hope and think it mattered to them a little. You don't have to commit to a point-of-view to listen to it with sympathy and respect. It helps build rapport that can make a resolution more palatable.

Eliminate the concept of "zero tolerance". It's always a lie. There is no such thing as zero tolerance. In practice, zero tolerance means that organizations often redefine the behavior of kids/people with social capital or advocacy as something other than the thing for which we have zero tolerance. Kids/people without social capital or advocacy get eviscerated anonymously. Because zero tolerance. Focus first on easing suffering, not imposing fake zero tolerance consequences.

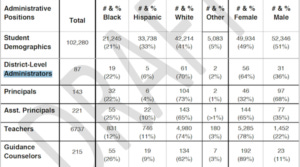

If girls are reporting sexualized bullying, have a woman available to them. Roughly 70 percent of our principals in Polk are men. Many are former coaches. Put aside whether that's a good or bad thing.

I think men of adult generations, especially men from locker room backgrounds, have a lot of imaginative work to do if they're going to help girls who report sexualized bullying by boys in the #metoo era. Fortunately, most of our assistant principals are women. That 70 percent number is going to change over time. If I were a principal, I'd be talking to my female assistant principals and guidance counselors about their own experiences and thinking real hard about how to make professional women available to comfort and guide girls.

Recognize that LGBTQ kids are much more visible than in the past -- and at much elevated risk for depression and suicide and cruelty. All the stats make it clear. We cannot ignore that humanity. The treatment LGBTQ kids in Polk will be a source of controversy for a long time because of beliefs about the nature of their identities. No one can snap a finger and fix that, although I think we are moving in a healthy direction. In the meantime, I hope we can all agree that all kids deserve to live with simple human kindness and respect.

Here is the gold standard of institutional leadership in the face of group harassment. This clip came from the US Air Force Academy not long ago. After racial slurs were found at the USAFA prep school, the leader of the academy did this:

Of course, USAFA is highly-selective, elite national institution. GET OUT can and should apply there in ways it cannot in a compulsory public education setting. But I do think our military-themed or connected schools can apply something close to this. And they matter because the military is synonymous with power and leadership.

Moreover, there is great virtue in setting expectations of behavior publicly, even if you can't fully enforce them. There's great virtue in the leader of an organization grabbing the bullhorn -- or the camera phone -- and stating his moral point of view clearly to his or her leadership subordinates.

Recognize most "bullying" and violence happens within "friend" groups. Finally, my experience dovetails with many, many conversations I've had with school officials. It sounds obvious, but fighting and bullying tend to happen with kids who have some level of intimacy with each other. You fight your "friends." And the intimate rage that drives fighting and bullying can be deadly in one moment and gone in the next. The emotions of children -- like the emotions of many adults -- surge and fall. An act of "bullying" or "violence" does not make one a "bully" or a "thug." Most likely, it makes one a child who is hurt, angry, or scared about something with intimate importance to them. The label of "bully" is probably harmful to everyone. But it exists. It's important to think critically about it.

Our obligation to try the impossible

I've been trying to do a math problem. I want to calculate how many potential human interactions exist during any single day of the Polk School system, with human interaction defined as a 10-second increment of time.

103,000 kids. 6000 or so teachers. Another 7,000 or so adult employees. 7-8 hours a day, plus many more extra-curriculars. I think you get way, way into the trillions, if you can even calculate a number at all. My command of exponents and probability isn't good enough to say with certainty. (Perhaps Paul Cottle can help me.)

But let's agree that it's a big, big number, a number so big it confounds my ability to represent it mathematically. Now imagine humanizing that number, trying to identify, represent, and address the pain, sadness, and anger it contains at the level of individual children.

That number contains much less of the pain, I think, than it does joy, friendship, and care. But individual pain motivates critical expression more than individual joy drives group celebration. That's why individual schools and teachers are generally popular and loved -- when education systems are not.

When people ask me about the challenges we face as a district or state or country in public education, I always say "scale" as the first. The sheer volume of human experiences contained in any school district can overwhelm human attempts to individualize and shape them.

I ask the public and parents to understand the general impossibility of what society is now demanding from the humans of our institutions in regards to bullying and childhood suffering. At the same time, we adults in schools have the solemn obligation to try -- and fail -- as honorably and intelligently and morally as we can.