Godspeed, Gary: a free, accepted American turkey

A brief history of Lake Morton's Gary, and the bird(s) who loved her, as imagined by Billy

As a 20-year resident of greater Lake Morton, I tend to walk/jog the lake regularly. Among her many blessings to our neighborhood, “Gary,” the-transplanted-female-wild turkey, gave me an excuse to stop running and take pictures of her. She truly was a majestic, beautiful bird.

I took this at 3:12 p.m. on Thursday — Christmas Eve. That’s Gary — in perhaps the final image that captured her alive — and what I think is a Muscovy duck.

The day before, I took the picture below, the world’s worst selfie. That’s Gary and what seems to be the same Muscovy duck.

I came home from the Christmas Eve picture with an emerging theory: Gary had found herself a boyfriend; or a girlfriend; or a best friend.

I speculated to my lovely wife, Julie, a long-time poobah of the Lake Morton Neighborhood Association: “I think Gary’s here because she’s in a relationship. And the duck looks a little bit like her, with the color scheme. They both have the splotch of red or pink. Similar size and shape when foraging. I wonder if Gary confused it for a turkey; and the duck just went with it. And all the rest of the duck/swan/pelican/gull/turn/ibis/whatever waterfowl friends said, “Sure, yeah, we’re a lake of multitudes and love wins in the end.” How sweet. You know, birds not of a feather…the bird couple that forages together…etc.”

This morning, I awoke to Julie standing stolidly in our bedroom doorway:

“What’s wrong?”

“Gary’s dead.”

The Ledger has the story here.

Lakeland Parks and Recreation Director Bob Donahay said the cause of death is uncertain, but it doesn't look like any foul play was involved.

"It just looked like it died," Donahay said. "(The employee that retrieved the bird) said it was floating in the water. There's not much I can tell you. It didn't look like an animal got it.

"I know the neighborhood got really attached to it. I didn't want them to walk along the shore and see him floating there."

I appreciate Bob’s lack of official information.

That’s his story; and he should stick to it. The last thing 2020 needs is hardcore Gary journalism as it finally lurches to its wretched end. But…

Beloved turkeys deserve epic backstories

In the absence of official information, it may or my not surprise you that I’ve channeled my Gary grief into some research — and an inspiring backstory.

I found this from the “National Wild Turkey Federation”:

In general, the average life expectancy for hens is three years and four years for toms. Everyone likes to blame predators as the chief factor when discussing a wild turkey’s life expectancy, but, while predation is no doubt a factor, there is a larger process to consider.

The NWTF’s director of conservation services, Mark Hatfield, points out a wild turkey’s life expectancy correlates to where it lives; that is, the farther a turkey must range to gather resources, its life expectancy decreases.

Wild turkeys that have to leave the safety of their roosting area and travel long distances to areas with more abundant food and water are expending more energy to reach those resources.

When I look at Gary, I see a senior turkey. The blanket of gray around the neck and rear feathers suggest advanced age to me — as does her size. It must have taken a while to get that big.

Also, I never saw Gary move very quickly, or with any real fear, for which I’m probably lucky.

The first time I ever saw Gary, in the middle of the lake-facing sidewalk in front for the library, I was lost in a podcast or my customary deep thoughts. I was less than 10 feet away from her when I realized: “there’s a wild turkey immediately in front of me. Oh, that must be Gary.”

At the same moment, Gary seemed to realize a burly, absent-minded man was lumbering toward her. She took several half-hearted steps toward the street, where a Lakeland police command vehicle happened to be approaching.

For a brief, horrifying instant, I thought to myself: “I’m about to watch Gary the beloved female turkey get killed by a Lakeland Police vehicle because I was listening to my Star Trek podcast and not paying attention. How will I explain this to anyone?”

Thankfully, Gary proved too pooped to gobble — or gallop — and all ended well. She was nice enough, or tired enough, to pose for this picture after I realized who she was.

Turkey experts say you can get a more precise reading on turkey age by measuring spikes on their legs. But I hope nobody asks for an autopsy. I prefer to anthropomorphize the animals of my affection into epic backstories worthy of their impact on the community.

So here it goes.

From Gator Creek to Lake Morton, a heroine’s final journey

The only other place I’ve ever seen a wild turkey in Polk County is in Gator Creek Reserve, just north of Lakeland off U.S. 98. And when I ask myself, where could a wild turkey grow to adulthood — and even elderliness — the only options seems to be Gator Creek or Circle B. Both have water-based ecosystems at their core.

But Circle B is overdeveloped with hordes of alligators. As a general rule, I’d wager that turkey life expectancy is inversely proportional to alligator density per square mile.

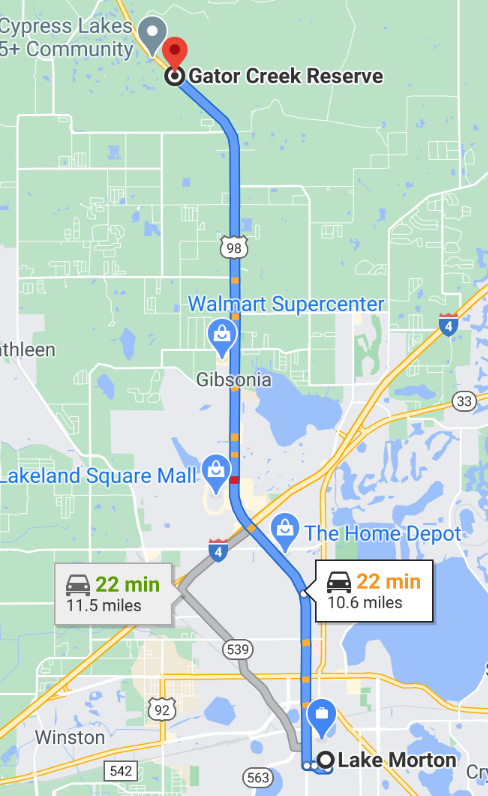

Plus, the path from Gator Creek to Lake Morton seems more logical. See below:

If you leave Gator Creek and follow the hurly-burly of cars and nourishing detritus of commerce south along U.S. 98, Lake Morton is first lake you can probably see from the road — or notice fellow birds loitering around doing bird things at scale.

So I think we’re looking at a Gator Creek-to-Lake Morton Odyssey here. Yet, that’s no easy 10-mile hike for a human, much less for an elderly turkey that had presumably never played seen or played “Frogger.”

An omnivore looks for love — and an illustrator

So you have to start with a question? Why? Why would Gary leave Gator Creek for parts unknown? That depends. Are you making a Pixar movie or an Alec Baldwin/Meryl Streep romantic comedy?

I see this as akin to an “Up” situation — with Gary perhaps mourning the passing of the Gator Creek Tom who had made her a happy hen in life. Their little turkeys are busy, out doing turkey things, looking for hens and toms of their own, trying to start turkey careers and families. Or maybe there are no little turkeys because the wild can be a harsh place.

In any event, I envision Gary as lonely and in search of one last adventure — and a final chance for fowl-to-fowl connection.

Julie sees the “why” question a little differently, with a more darkly modern sensibility: “She got dumped for a younger turkey.”

That’s possible; but I’m doing a heart-warming family story here; so we’re sticking with my modified “Up” premise. (And I’m the sentimental one, dear, you know that.)

I found this information about how wild turkeys eat. Like me, they are “opportunistically omnivorous”:

Wild turkeys are opportunistically omnivorous, which means they will readily sample a wide range of foods, both animal and vegetable. They forage frequently and will eat many different things, including:

Acorns, hickory nuts, beechnuts, or walnuts, either cracked open or swallowed whole

Seeds and grain, including spilled birdseed or corn and wheat in agricultural fields

Berries, wild grapes, crabapples, and other small fruits

Small reptiles including lizards and snakes

Fleshy plant parts such as buds, roots, bulbs, succulents, and cacti

Plant foliage, grass, and tender young leaves or shoots

Large insects including grasshoppers, spiders, and caterpillars

Snails, slugs, and worms

Sand and small gravel for grit to aid proper digestion

The journey south along U.S. 98 just calls out for a talented children’s author to illustrate. (Fred Koehler, do you know anyone like that?)

When you match Wal-Mart and Home Depot and Bryant Stadium and the Polk Theater to how turkeys eat, the possibilities for a cutely profound local take on American capitalism seem endless.

Or maybe you could just illustrate a bunch of funny sight gags and sell it as a fundraiser for the Lake Morton Neighborhood Association and some sort of year-round Gary marker to go with this holiday addition to our night sky.

When Gary met Marge

Just when Gary’s spiked little turkey legs seemed like they could carry her no farther through downtown Lakeland, she looked to her left along East Palmetto and saw a little crew of Muscovies hanging out by the Wilsonian apartments.

“Do any of you urban fowl speak gobble?”

One Muscovy duck, with a kind bill, answered. “Yes, ma’am. I’ve known some turkeys. But none quite like you.”

“Oh thank goodness, I am a weary north Lakeland country hen who misses my tom and is sick of eating road side cigarette butts.”

“Well, you’ve come to the right lake, then.”

And so Gary met “Marge” the male Muscovy. (Note to oversensitive readers: I find “Gary the female Turkey” and “Marge the male Muscovy” a funny couple of bird names to imagine dating — because of the alliteration and the symmetrical gender-norm name inversion. That is all. Please read no other commentary into the joke I have now ruined. Carry on.)

Marge was immediately smitten by Gary’s inherent goodness. He saw immediately that the trip, so far from her lifetime foraging ground, had taken a toll. He took Gary under his wing, so to speak, and set about nursing her back to full health and heart.

Marge laid out the anthropology of the Lake Morton scene as he led Gary to food.

“The swans seem to think they’re better than you at first; but they’re just proud and serious and British — kinda like the Queen,” he said. “That’s where they’re from, you know. And they act like they’re royals. But they’re always loyal to the lake in the end; and we all kind of look to them in crisis moments. It’s the geese you really gotta watch out for — they're kinda assholes. And they’ll gang up on you.”

Gary nodded and gobbled with gratitude to her new friend’s care, her neck waddle cheerfully flapping like a fleshy smile.

Marge went on: “The humans are OK, especially when they’re not in their cars. I hate cars. When they get out, they give us this stuff called bread. It is not good for us — and we cannot stop eating it — but it is yummy. And they seem to like the attention. Humans, above all, seem to like attention. And they stick signs in their yards with people’s names on them and get very heated about it. They’re strange.”

Gary gobbled again.

But she added, with the regal earnestness earned of a long three-year life among predators — and an arduous journey to a new world: “All creatures need affectionate attention, these humans more than most from what I could see from how they behave when they drive. I think they’ve had a tough year, too. Maybe I can spread a little happiness.”

As it turned out, Gary was right: she found the good in the swans and the geese and the humans alike with her tales of wilderness life and her weary kindness. They all welcomed her in turn; but she and Marge were inseparable until the end.

And, you know, four months or so in a three-year wild turkey lifespan is basically a decade for a human. That’s a pretty good final act.

A final gesture of belonging

When Gary finally passed, softly and gently at the water’s edge, she was surrounded by her waterfowl community.

And like the Vikings of old, they set her afloat. They couldn’t fire flaming arrows at her because it’s too hard to string and shoot a bow with flipper hands. But the thought was there. She was one of them, a turkey that became an urban water bird and died loved and welcomed.

My research tells me that domestic turkeys bred for food only live a few months until they are the appropriate size to make a human’s dinner.

Gary, free turkey of Lake Morton, showed us all there are better paths to the human heart than the stomach.

She will be missed and remembered.