Gratitude and longing: the promise and burden of Leo Schofield's remarkable manhood

After 35 years of work and waiting, life on parole, without capital, means more work and waiting for the Schofield family. Leo and Chrissie and Ashley can see freedom; but they can't touch it yet.

Leo Schofield is 58-years-old.

He works 11 hours a day, six days a week for minimum wage in a Tampa mechanic shop. When he returns to his room at the Noah Community Outreach halfway house in Tampa for the evening, he generally works a few additional hours for a remote job. Whatever time is left over, Leo usually spends on the phone with his daughter, Ashley, who has three children of her own now.

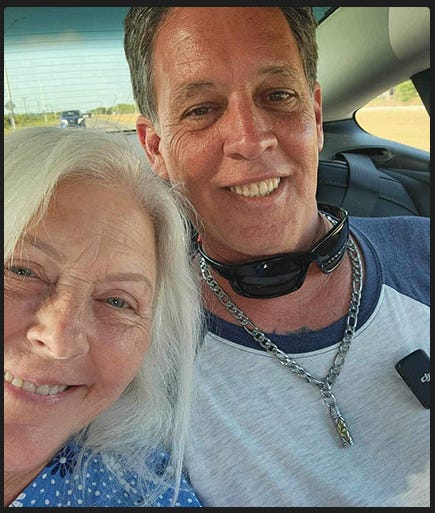

“He’s working his butt off,” says Leo’s wife, Crissie Carter Schofield. “He feels bad about not being there for his family all those years; and providing for his family is his number 1 priority.”

Manhood, as a subject, has featured prominently in recent articles I’ve written. I’ve been thinking about it quite a bit. And it’s hard for me to imagine a husband and father trying harder, under more challenging circumstances, to embody the values of a responsible man than Leo Schofield is today.

And it’s hard to imagine a wife and mother more loyal and virtuous in her own right than Crissie Carter Schofield.

Parole is not freedom

More than three months after Leo’s release on parole following 35 years wrongly spent in Florida prisons, Leo and Crissie are hopefully halfway to a relaxation of community control measures. But today, husband and wife are still only permitted to speak to each other through the invisible bars of the Noah property line. Crissie is not allowed inside.

Moreover, well wishers like me can’t just go check Leo out for the day to take him to lunch or dinner. He must plan ahead his weekly permitted trip to the grocery store. And while Leo has the benefit of company from the men who share his life within Noah’s, with whom has has started a Bible study group, that community ends at the property line; it does not extend to Crissie.

“We haven’t been alone yet,” she told me, describing each day as a tension “between gratitude and longing.”

That’s all because the state of Florida refuses to admit what anyone with a pulse, of any political persuasion, who has reviewed the case at all, knows to be true: Leo Schofield was wrongly convicted of killing his young wife Michelle Schofield in 1987.

The actual killer, convicted murderer Jeremy Scott, left fingerprint evidence in Michelle’s car the night she was killed. And Scott has confessed to the crime in escalating detail, consistent with the details of the crime scene. No physical or eyewitness evidence ever tied Leo to the killing; and the inferential eyewitness testimony was discredited as mistaken or just wrong during the trial.

Nevertheless, a jury convicted Leo Schofield, largely based on testimony about his temper as a young man and accusations of abusing Michelle. And Florida refuses to retry Leo with the Jeremy Scott evidence, which was not available in the 1989 trial.

When the attention fades

A major wrongful conviction case like this tends to end in a large compensation payout for the wrongfully-convicted. One Tampa man wrongfully convicted of rape in 1983 recently won a $14 million settlement, for example.

But again, Florida won’t admit it got Leo Schofield’s case wrong — even though everyone behaved like it at his parole hearing.

So despite all his support and strange fame today, Leo Schofield still must find a way to feed himself and pay his bills and support the family he managed to build in prison. Until the state of Florida owns up to its mistake and makes some reasonable restitution to Leo, he and his family are their own.

Crissie is a social worker in southwest Florida’s Lee County, who has shouldered the responsibility of supporting that family for years. Leo is trying to ease the burden.

Various forms of media documented the day of Leo Schofield’s release. Bone Valley followed Leo to the Noah Community Outreach center where he lives today. ABC News was there. Here’s an excerpt from its article:

"I saw him come around the building," Crissie Schofield told "20/20" about the day Leo Schofield was paroled. "After all these years and dreaming and hoping and waiting, it was just the most glorious, magical experience of my life."

Leo Schofield's legal team said he must reside in a halfway house for a year, enter a community outreach program and undergo mandatory mental health, substance abuse, anger and stress evaluations. He also has 18 months of curfew restrictions and is not allowed to contact Michelle Schofield's family.

Since then, attention paid to Leo Schofield’s family and case has understandably waned. So I decided to reach out to Crissie Carter Schofield a couple weeks ago.

Crissie and I have had an occasional Facebook correspondence; and I wondered about the experience of trying to build a normal family life from less than nothing — from the capital deficit of convicted-murderer status for one spouse. And I wondered about it from her point-of-view.

If you know the Schofield story, you know that Crissie is more responsible than anyone for the public recognition that Leo is innocent. She met, fell in love, and married Leo when he was in prison. Together, they adopted Ashley. And through sheer will and connections, Crissie made the Jeremy Scott fingerprints into evidence and drew prosecutor-turned-defense attorney-turned-judge Scott Cupp into the case 20 years ago.

As I spoke to her in August, it was clear that the euphoria of Leo’s parole is tempered by the painful restrictions of tight community control. She described the challenges for me, while over and over again emphasizing: “I don’t want to come across as ungrateful.”

I found her incredibly honest, sympathetic, articulate, and loyal.

Imagining her standing in the street outside Noah’s stealing marital moments where she and Leo can is heartbreaking.

Where is home?

Leo is obviously a model parolee. So there is a strong possibility that the strictest community control measures will end at the 6-month mark of his oversight. But that’s not guaranteed, as I understand it.

And even if Leo is allowed to go home to Crissie, it’s unclear where the home would be. Crissie lives and works a couple hours away in Lee County. Leo’s job is in Tampa. Crissie drives a beat up van back and forth on weekends.

Now that I’ve spoken to Crissie about this, I’m openly hoping some rich person will read this article and provide the Schofield family with some start-up capital — whether that be house, vehicle, college fund for the grandkids, anything.

I should be clear: this is me talking. Neither Crissie nor Leo are asking for anything. But that doesn’t mean they — and their children and grandchildren — aren’t deserving of atonement, support, and compensation.

If the state won’t own up to its responsibilities, hopefully the community or private individuals will step in.

In any event, the Schofield story, in all its human outrage, sadness, and inspiration, did not end when Leo left prison.

In fact, it seems to have just begun.

Sadly the system is flawed. Our entire justice and prison systems need overhaul along with cleaning out the rot and corruption in these systems. From the top at federal layer down to state and local has decay and rot. And if you have money you buy or bribe your way out!