Sheriff Judd seems to misunderstand his own law. So let's start over, as serious and collaborative people.

The "School Security" law your legislators and Polk Sheriff Grady Judd recently produced swallows itself in fundamental and lethal contradiction.

Ideally, all stakeholders would recognize this and simply start over again. Ideally, this time, lawmakers and Judd would seek good faith collaboration with subject matter experts in school operations.

But we don't live in an ideally governed state.

Thus, it's vitally important for you, the public, to understand this paradox: to implement Grady Judd's Guardian program consistent with Grady Judd's vision for it, which the state law wants to coerce your School Board to do, your School Board will have to break the same law Grady Judd helped create that is trying to coerce us. And by breaking Judd's law, we will create massive daily firearm accident risk and impulsive behavior risk -- the exact type of daily risk Judd seeks to avoid in his jails by preventing detention deputies from carrying weapons while performing normal duties.

[Kids are not prisoners. Schools are not jails. But schools are full of human immaturity. These children are developing. Depending on their ages, they can be grabby, impulsive, angry, depressed. Some have disabilities that impair judgement. Some feel suicidal. A gun is power. It will exert the same gravity and endless possibility of violent disruption in a classroom that it will in a jail. It is a deadly, shiny object. See a full examination of that here.]

I know that's quite a bit in one paragraph to wrap your head around. I took me a long time to figure out how to articulate it. But this glaring contradiction at the heart of the law stems from three key facts:

The Guardian program is an "arming teachers" program that excludes teachers from being armed.

Elementary schools, which have the fewest security incidents, pose the most vexing cost, logistics, and safety challenge because they don't have school resource officers. And there are a lot of elementary schools.

The law requires either a school resource officer or "guardians" at every school, including elementary schools. But the state does not fund SROs for elementary schools. Thus, it seeks to strong-arm boards into "defending" elementary schools with a Guardian program that doesn't actually arm teachers.

Let's look at each of these in a little greater depth.

The Guardian program is an "arming teachers" program that excludes teachers from being armed.

Arming teachers is an unsound operational and moral idea for the reasons I laid out in this post and this post and this post.

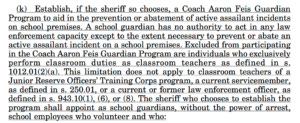

But, ironically, the law that Sheriff Judd and Richard Corcoran and Rick Scott created doesn't even allow for arming teachers. Here is the relevant passage:

Notice the sentence that reads: “Excluded from participating in the Coach Aaron Feis Guardian Program are individuals who exclusively perform classroom duties as classroom teachers as defined in s. 1012.01(2)(a).”

There is potentially some wiggle room in the word, "exclusively", I guess. And there are some exceptions for current military/ex-law enforcement personnel. Maybe you could staff it with loopholes and exceptions.

But listen to Sheriff Judd in this 90-second clip from our work session. This isn't someone talking about loopholes and exceptions. This is an entirely different model and mindset from what the law actually allows.

Some key excerpts:

"Now some people don't want teachers to have guns because of a trust issue...we trust these teachers every day to teach our children and keep them safe and they do..."

"School teachers and staff members are charging active shooters with nothing to protect themselves...why wouldn't you want to give them one last best opportunity to stop the active shooter from shooting your child or our grandchildren."

Does that sound like someone who understands that his law rejects arming the vast majority of teachers who "exclusively perform classroom duties as classroom teachers?" He's talking dramatically about a defense layer that his law does not even allow. By every understanding I have, at least one of two Polk teachers I have spoken to who advocate carrying a weapon is legally ineligible to do so. And neither of them work where the core of the resource problem lies: elementary schools.

Elementary schools, which have the fewest security incidents, pose the most vexing cost, logistics, and safety challenge.

The cost of providing school resource officers for elementary schools, which generally do not have them now, is formidable. It accounts for most of the $16 million start up, plus $11 million per year recurring cost, that Sheriff Judd cited in his appearance before us.

Your state legislators -- looking at you, Kelli Stargel -- will not pay for it. Moreover, law enforcement seems to want nothing to do with overseeing all those new resource officers. I don't blame them much. I think most law enforcement, quietly, finds the idea wasteful and unnecessary. I think they believe, rationally, that dozens of new officers could be better put to work in the community as a whole. But that's just my observation and inference. And the community as a whole seems to want resource officers at every school, elementary and otherwise.

I do think it's safe to say that serving as SRO of an elementary school, especially an SRO focused on repelling outside threats, is going to be the most boring job in the history of law enforcement -- right up until that terrible moment somewhere in America when it isn't.

Thus, the debate over SRO versus Guardian is really a debate over how -- and to what degree -- to secure elementary schools.

By not funding resource officers, the law tries to strong-arm boards into "defending" elementary schools with a Guardian program that doesn't actually arm teachers.

As Sheriff Judd put it in our work session: "You could get 32 guardians for the cost of one school resource officer."

The sheriff then made it clear at our meeting that if if the School Board does not accept his Guardians-instead-of-SROs deal, which he helped create without our input, he will publicly declare that we are "shortchanging [law enforcement's] ability to keep you and the children safe."

Here's the full clip. Watch it. It's important. Note the time urgency.

If you don't want to watch, let me summarize for you quickly. Judd was concluding his long presentation and said this:

"A successful program needs affordability, sustainability, and feasibility. We have a very short time to get there. It's only 153 days until the first day of school on August the 13th.

"Let me underscore one last time, we're your subject matter experts; we're your allies; we're your friends. You know and I know I love ya'll. [Polk Superintendent] Jackie Byrd is one of my heroes. We are here because we care about you and the staff. And we're going to do everything that you allow us to do to keep the children safe."

He then immediately pivoted to the consequences he plans to deliver to his friends with the School Board/District if we do not embrace all of his recommendations with haste.

If we reject anything he suggests, Judd said, "I am publicly going to say you are shortchanging our ability to keep you and the children safe. But that's your decision. You have to make that. And I certainly can tell you that you have our undying support for this."

I'm happy for the sheriff to say whatever he wants in public. It's one of the reasons I admire him; because I am also happy to publicly explain my judgement and critique his. I admire Sheriff Judd because he gives me something tangible to engage in public, which is where consequential debates should happen. This back and forth serves our shared community well.

For me, Judd's ultimatum shows that he did not take time to think through the contradiction he helped create during the Legislative session. He did not take time to think it through before he confronted us with what he planned to say about us if we disagree with him -- or just point out the sheer logistical infeasibility of his program.

By contrast, I don't have the luxury of not thinking. I represent the same people he does; but I'm not as powerful as he is.

Florida state government at its cynical worst

Too often, in the aftermath of a traumatic event, government legislates first and thinks second, if it ever thinks at all. That's exactly what happened in this case.

In Florida, this understandable human instinct is compounded because Tallahassee houses America's worst, most cynical, and most morally corrupt state government. Florida's state government is also the most hostile in America to teachers and the very idea of public education. Kelli Stargel's every action for a decade has signaled that she despises both.

So it's fascinating to hear Sheriff Judd say this: "We trust these teachers every day to teach our children and keep them safe and they do."

No, "we" don't: not if "we" is the state of Florida. Florida despises and utterly distrusts its teachers. The Florida Model runs on distrust.

No, "we" don't: if "we" includes Rick Scott and Richard Corcoran and Joe Negron. And yet, that's the "we" with whom Sheriff Judd collaborated to create this completely unworkable law.

Make no mistake. See this story. This is Judd's law, as much anybody else's.

The wide-ranging opposition had legislative leaders scrambling to rework the proposal to find enough votes to narrowly pass the measure through the House and Senate. By the end of Friday, one potential compromise had emerged: instead of arming teachers, train school staff, such as coaches, hall monitors and other personnel, to carry concealed weapons.

[Billy insert: "hall monitors"? Who are these hall monitors of which they speak?]

Senate President Joe Negron, R-Stuart, said the idea came from the governor who has ideas about "non-teaching personnel — coaches, security monitors, administrators and others — perhaps being on the front lines of protecting the schools."

The idea of training and arming teachers was proposed by Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd and has become a top priority of House Speaker Richard Corcoran, R-Land O'Lakes. Black lawmakers, however, said they will vote against the bill until the provision arming teachers is removed, arguing that it may disproportionately target black students.

But the head of the NRA's Florida chapter, Marion Hammer, said Friday that her organization could live without the program to arm teachers as so-called marshals, as long as whatever lawmakers pass includes more armed law enforcement in schools.

"We're not married to either plan," she told the Herald/Times. "We just want armed security in the school to protect the kids.

Marion Hammer's crucial "veto" role here is one of the reasons that I asked Sheriff Judd if he belongs to the NRA. He wouldn't answer. In fact, he said quite pointedly that it's "none of your business."

That's definitely a difference between us.

I would have answered, in his place. You can ask me about any affiliation. I will answer. I think I owe that to you. I think my loyalties and affiliations are very much "your business" in evaluating how I do my job on your behalf.

In any event, I think Sheriff Judd's local School Board would have been a much better "we" for Sheriff Judd to engage than Marion Hammer's Tallahassee marionettes.

A willful failure to understand elementary school staffing

Your awful, irresponsible state government does not understand or care how the public schools it oversees are organized; what their staffing plans look like; what their demographics look like; their funding shortfalls; the stressful duties that administrators, teachers, and staff are expected to perform; and the overall level of intensity and attention required each day from the understaffed and underpaid people who work there.

So predictably, it threw together hasty, unimplementable nonsense that "we" now have to deal with at the local level. It's the same as every other terrible education bill dropped on us for years.

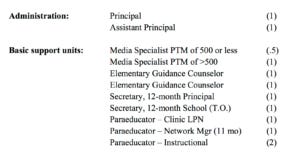

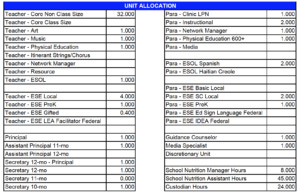

But let's look closer at this willful failure to understand by considering Judd's 32:1 Guardians vs. SROs equation in the light of the two images below. The first is the base staffing plan of every Polk County elementary school.

Depending on the size and characteristics of enrollment, principals have a menu of additional potential positions they can select. The image that follows is the full staffing plan of an actual elementary school in Polk County, known commonly as a "blue sheet."

I've asked Polk School District staff if anyone -- Sheriff Judd, our legislators, Rick Scott, anyone -- bothered to ask for a look at our school staffing plans as they "crafted" their plan.

Guess what the answer is.

The particular skills of Grady Judd's commandos

As we've established, the Guardian law excludes teachers. And if you exclude teachers, you need to exclude most paras, who perform many of the same intensive academic and behavioral support duties.

Who do you have left to act as Grady Judd's last line of defense against a shooter?

A principal, an assistant principal, guidance counselor, a media specialist, a couple secretaries, a PE coach and PE para, (who have more active and intensive child management duties than anybody else while teaching), an LPN, a network manager, a custodian, and four or five food service workers. (The hours mentioned for food service and custodial translate, essentially, into one full-time day custodian and a handful of part-time food service workers.)

With slight variations, this will be the same pool of eligible Judd commandos at each elementary school. Food service is the largest single pool of personnel; and it's not large.

Most, if not all, have demanding, attention-intensive jobs -- other than security -- that involve sustained interaction with children. And because the state refuses to fund education adequately, we do not pay most of these commandos a real living wage. Nor will we in the future as long as your current state leaders run things.

Moreover, the vast majority of these eligible Judd commandos will be women, including the coaches. Particularly at the elementary school level, where resource officers are most scarce, the Coach Aaron Feis Guardian program will actually be the Media Specialist Annabelle Jones Guardian program.

Let me be clear: women are just as likely as men to handle a weapon effectively. And they're just as likely as men to use a concealed pistol they pull from beneath their blouse or dress to successfully repel AR-15 fire from a suicidal attacker. And by just as likely, I mean highly unlikely.

However, women in schools are not likely, from all public opinion research I've seen, to want to carry a weapon while doing their jobs amongst their kids.

I also raise this issue of gender because it's important to point out the fantasy image this poorly conceived plan has tried to conjure: a bunch of Liam Neesons, with a "particular set of skills" provided by Grady Judd, doing heroic movie things. Policy by movie is always destructive. At the elementary level, I suspect it can't even be implemented with current staff, which is probably a blessing.

Judd is right about how many elementary school teachers and leaders are willing to die for their kids. But I think he misunderstands how unwilling they are to risk killing their kids every day, even if we break his law to allow them to do it. I talked to an elementary principal just last week -- one of our finest, I believe -- who laid out this exact same moral equation to me.

I think Sheriff Judd tragically misunderstands the enormous bravery and strength of humanity that displays.

Moreover, she does not want guns at all in her school. If we impose them, we'll be doing it against her will. Are we going to give principals veto at the school level? How many elementary principals, who we can't afford to lose, could we lose over this?

The Guardian program isn't Southeastern's Sentinel program; a private university is not a zoned public elementary school

I have great affection for Southeastern University; but it is a private Christian college for adults who choose to attend. There is not one faculty job at Southeastern that requires a quarter of the intensity of interaction with needy children required from EVERYONE at a neighborhood public school. Southeastern's campus is also much larger than a typical school, with fewer people on top of each other. There are no behavioral considerations to speak of.

Thus, Southeastern's Sentinel program is completely inapplicable to compulsory education public schools. It's also worth noting, especially in the light of the elementary school staffing structure, that roughly half of the original Sentinel applicants didn't make it through the extensive Sheriff's Office training, Judd told us. Nine did make it through. Think about those numbers and go back and look at the zoned elementary school staffing plan.

Any serious legislator or public leader trying to create and then back door mandate this program would have taken the time to consult "subject matter specialists" in compulsory public school operations. Any could have explained the fundamental difference between Southeastern University and compulsory education public schools. I tried to do it in great depth via web essay and Twitter and Facebook. No one in power listened.

Not understanding the difference will prove deadly if your School Board is coerced by funding into breaking the Guardian law and jamming 1500 guns into our Polk schools, which is what the state Guardian funding envisions.

Indeed, at virtually the same time Sheriff Judd and I were talking during our work session, a law enforcement trained teacher in California, with a particular set of skills, accidentally fired a gun in a public safety class and wounded multiple children.

Now multiply that by 1500 or more guns just in Polk County schools over the next 20 years. I'm sure Sheriff Judd's training is excellent. But we're still dealing with human beings. This program will kill some number of kids. I promise you.

And there is absolutely no guarantee that any armed staff member will do anything but add to the body count during a mass shooting, should one occur, which is certainly possible, but unlikely.

How can we move ahead together

Let's look again at one of Sheriff Judd's key quotes:

A successful program needs affordability, sustainability, and feasibility. We have a very short time to get there. It's only 153 days until the first day of school on August the 13th.

I'm sorry to say that every bit of lawmaking and policymaking I've seen thus far has been a waste of time. It has created hurdles and distractions that hamper our ability to provide common sense and "sustainable" security enhancements.

By contrast, our law enforcement partners here on the ground -- very much including Sheriff's Office personnel -- have been enormous helpful and collaborative in daily operations. I'd like to see us all move forward with law enforcement and community partners with that level of collaboration, common purpose, and clear thinking.

Here's what happening in the immediate term:

The most practical measure has been police presence. Across the county, our city and county law enforcement partners have been fantastic in finding ways to place their officers in visible school locations. That sends a message to the outside world and to our stakeholders inside.

We're also moving together on fencing and access issues, which are more complicated than you might think. Single-point-of-entry sounds good in theory; but execution matters more than theory. We need to be thoughtful and careful, which I'm confident we are being. I hate the word "hardening" in this context. It's unnecessarily military. And it's important to me, as a board member, that we preserve the sense that these are places of learning and human engagement, not grim fortresses.

Here's what I propose in the short-middle term:

Commit to putting SROs in every middle school as soon as we can.

Many middle schools already have them. I don't have the precise position-to-funding ratio; but I suspect we can get very close to fully staffing middle schools with the limited SRO funding the new state provided. That would provide every middle and high school with armed, uniformed human security. There is also a more useful daily role for SROs at middle schools than elementary schools. The sheer size and day-and-night activities of those older child campuses make "hardening" measures extremely challenging.

Prioritize fencing everywhere -- and physical campus upgrades for elementary schools

By contrast, elementary schools are smaller, with much less going on after hours. They should be easier to secure from a physical plant point-of-view. Other than fencing, let's prioritize our limited campus security upgrade dollars for elementary schools -- doors, access, fencing, etc.

Use local sales tax dollars if voters renew the sales tax in November

I'm not allowed to advocate, as I understand it, for renewal of the half-cent sales tax for capital spending. But it will be on the ballot in November.

And I can tell you it's the only source of money -- of any kind -- that we generate and keep locally. Everything else depends on the generosity of our enemies in Tallahassee.

Because of the bonding structure created back when the tax was first approved, we've been using sales tax money in recent years primarily to pay off earlier construction. So renewal will be like passing it all over again. We will have new money available to deploy. It will be crucial to any longer term campus security improvements.

Reject any wasteful consultant mandate from Tallahassee

Keep in mind that the Kelli Stargel School Kill List is still out there: Kelli Stargel and the same legislators who brought you this security law want to close, outsource to non-existent charter operators, or outsource to consultants a dozen or so Polk schools in the next two years.

The most likely option seems to be wasting hundreds of thousands of dollars on consultants.

We were supposed to vote on this choice on Feb. 27. I planned to vote against all three options and force our enemies in Tallahassee to do their own dirty work of hurting our kids, teachers, and communities. But the vote was postponed indefinitely. My position has not changed.

But in a time of laser focus on mental health, no one should support wasting taxpayer money we might spend on counselors and human support on educratic consultants because Tallahassee tells us to.

A welcome glimmer of collaboration

Ideally, state government would realize its confused failure and drop the lethal, unimplementable coercion inherent in the Guardian v. SRO issue.

But we're talking about Kelli Stargel and Rick Scott and Richard Corcoran. They don't care about lethal, unimplementable coercion. So, as a board and community trying to do the right thing, we just need to ignore them and do the right thing in spite of them.

And we, as a board, need to endure Sheriff Judd's public wrath if he feels the need to express it. I can live with a popular politician willing me out of office because I did my duty as a public official. It's happened many times to better people than me.

If, by contrast, the sheriff wants to work collaboratively, here's the core problem of elementary schools (really all schools) and human security in regard to mass shootings. We both see it. Watch this clip: it came at the very end of our session with the sheriff.

Key quote:

"Even Billy and I agreed on one thing. If you could magically get that gun at that moment in time when everything else has failed...and that's all we're talking about."

That's a direct quote, including the very, very telling ellipsis, which makes it clear that's not "all we're talking about."

There is no way to rhetorically wave off the fact that you can't "magically get that gun at that moment in time when everything else has failed." You must have that gun strapped to you always, every day, in close proximity to impulsive children, while you are distracted by doing your demanding, intense educational job.

Any moment of human carelessness and irresponsibility can blow a third-graders head off. And. it. will. Eventually. Believe that.

The key question of armed human security and elementary schools

However, I welcome Sheriff Judd's much more collaborative and productive sentiment in that full clip. It was better than anything that came before. So let's re-start there, where we should have started in the first place.

Let's consider this question together:

Can we provide the capability of rapid armed response to an extreme event at an elementary school without breaking the Guardian law, arming lunch ladies, and having guns in lethal proximity to grabby third graders seven hours/day, every day?

I don't know if we can. There may be no plan worth the risk trade-off. But I'm open to thinking seriously about it, without a proverbial gun to my head. Indeed, I am thinking seriously about it -- and have been for a while.

Here are some limited conceptualizations of how we might approach it:

In many cases, middle or high schools are very close to elementary schools. For instance, the SRO at Crystal Lake Middle can likely respond much quicker than anyone else to an incident at Crystal Lake Elementary. The campuses abut each other. I suspect there are many security efficiencies to gain simply through geography if we identify school clusters and design SRO presence and response around that. Where that proximity exists, we should loop older school SROs into elementary school communications.

Moreover, both Crystal Lakes virtually touch Southeastern. On its face, as an idea, I'm open to considering allowing the Sentinels to respond to either Crystal Lake campus in the event of a mass shooting attempt. I'd want school and community input first; but it's worth considering. That's a non-systemic possibility; but not every security benefit has to be systemic.

And that leads me to something else we might explore.

Rather than school personnel, what if we thought about looking for volunteers who live in close proximity to schools? Think of it as a volunteer fire department for mass shooting response, a mass shooting militia. The sheriff could administer it through the same level of training and background scrutiny the Sentinels receive.

That may be completely unworkable and unwise. I can think of a number of potential problems. And maybe we're better off thinking of it as more of a citizens patrol, where we rotate volunteers on a day-to-day basis to walk the school perimeter. Maybe we don't arm them; and we just have regular citizen patrols that report as a potential early warning.

Again, I'm not here to jam any of these measures down anybody's throat. These may be stupid and even deadly in execution. But I think they could be worth at least gaming out in a community that doesn't have a ton of consensus on this entire fraught issue -- beyond the fact that everybody will blame somebody for the next one.

What if, instead, we could get to a somewhat common definition of what security means and how to provide it? That would be a breakthrough for our community beyond just schools.

And of course, all of these thoughts are narrowly tailored around meeting violence with violence -- the "last resort." They are a small subset of my school safety vision.

I want us to focus the vast majority of resources and time and focus on the humanity of our kids, as I laid out in the comprehensive plan essay at this link.

Sheriff Judd is crucial

Wherever we end up, Sheriff Judd is going to be a vital player -- by virtue of his elected role as the country's top law enforcement officer and through his unique talent for public communication.

I think we can all agree that Sheriff Judd is a very powerful and persuasive man -- much more powerful than me.

If he had demanded full funding from Rick Scott, Richard Corcoran, Joe Negron, and NRA lobbyist Marion Hammer (who is like a fourth branch of government), we would probably have full state funding now for resource officers in all elementary and middle schools. But he didn't. And we don't.

It was a missed opportunity. It should be noted. It's left us with a law we have to break in order to implement it in the way he wants. And so breaking it, I believe, by virtue of statistical analysis, will prove deadly to some number of kids.

But Sheriff Judd is still an incredibly important player. We need him.

And we all need to figure out how to work together as responsible, collaborative public officials to balance safety and security with the richness of experience that public schooling, at its best, can provide.