"Storming mob repulsed at Putnam County Jail," 100 years ago today

Mark the centennial of Sheriff Peter Hagan, Florida's greatest cop, performing Florida's greatest single act of policing.

On March 2, 1923, just after 1 a.m., a Gainesville lynch mob arrived in Palatka to attack the Putnam County jail. I would bet my house that this mob included some of the same men who wiped out Rosewood three months earlier; but I don't know that with certainty.

The mob had come to abduct and murder a black man named Arthur Johnson, who was accused of killing a white road crew worker in downtown Gainesville. The two men had quarreled when the black man did not defer to the white man as they bumped into each other on a sidewalk. The accused killer was taken to Palatka, a northeast Florida town on the St. Johns River, for his own safety.

Putnam County Sheriff Peter Monroe Hagan met the mob at the front door. What happened next is a singular, largely unknown, moment in American history. I know of no historical act by any elected official that so completely unifies personal, physical, moral, professional, and political courage.

Brought down his pistol like a hammer on government-by-lynch mob

This is how I dramatized the moment at the jail door in my book Age of Barbarity: the Forgotten Fight for the Soul of Florida. Every moment of this, except some of the dialogue, is documented in contemporary sources, like newspapers.

Hagan pulled the chain on the bedside lamp, and the room went very dark and quiet. The window near [Hagan's terminally ill daughter] Gertrude's bed opened onto a cool, early spring Florida night. Nothing was stirring. After a while, Gertrude finally fell asleep, and Hagan walked across the hallway to his bedroom. He climbed into bed beside his wife, Sallie, about 12:30 a.m., a reasonable time for him. He'd be up by 4:30.

Much sooner than that, about 1:15, Hagan awoke at the sound of sharp banging on the outside door downstairs. He sat bolt upright in bed, listening to the impatient, incessant raps on the door. He jumped out of bed and grabbed the loaded pistol in the top drawer of his dresser in one hand and a loaded shotgun leaned against the wall in the other.

"Stay here," he told Sallie, who was also awake now, sitting up in her nightgown. On his way to the stairs, he stuck his head into Gertrude's dark room.

"Daddy?"

"Stay here, sweetheart. Don't get up."

Hagan moved quickly down the stairs to door, where the staccato knocking continued. He did not see Sallie follow behind him. Hagan set down the shotgun to the right of the door.

"Who's there," he called. No answer, but the knocking stopped. Hagan took a deep breath, slid back the bolt on the door and opened it.

Out of the night, a half dozen men with guns leveled them at his face. Another 10 or so stood behind. Hagan saw a large rope.

Instantly, the sheriff brought his pistol down like a hammer on the forehead of the man closest to him. The click of metal against skin-coated bone reported like a shot. The man crumpled. Hagan darted and spun to the left of the threshold as he slammed the door back shut. He jammed the bolt back into place with his left hand.

Just as he spun away from the door, gunfire exploded through the wood, and the room filled with sound and kinetic debris. Splinters flew from the door, mixing with an odd cloud of dark particles. With his back to the wall, Hagan for the first time saw his wife on the stairs. Inches from her face, plaster spray leapt from the wall and coated her right cheek in white flakes and dust.

"Go back," Hagan shouted, noticing a surge of pressure, but not quite pain, in his left hand. Eleanor turned and raced back upstairs. Hagan glanced to his hand and saw that a portion was missing, opposite his thumb, where a bullet had blown off a bit of meat from the thick part below his pinkie. Ragged, raw flesh roughly outlined the indention it left. Blood trickled to his wrist and dropped on the floor.

"Brown," Hagan shouted for his deputy. "Goddammit Brown. The mob is here. Get down here. I'm shot."

Outside, Hagan heard gunfire continue, but the foyer no longer seemed alive with projectiles and debris. Hagan thought he heard glass shatter upstairs. "Gertrude," he shouted. "Get away from the window."

No answer but gunfire. "Brown," he growled again.

He finally heard the heavy steps of his deputy on the hallway. He raced down the steps, nearly falling, as he contorted himself and ducked to make a hard target for the men he couldn't see outside.

"Sheriff, I think they're retreating. They shot at me twice when I looked out the window, and then a bunch of 'em were just shooting in the air, trying to scare people away, I think."

"What about my family?"

"I think they're fine. They shot into Gertrude's room, but missed her. I checked when I was coming."

This was the first time in Jim Crow Florida history that a white law enforcement officer violently repulsed a lynch mob looking to murder a black prisoner. Prior to this moment, Florida law enforcement either led, assisted, or maybe tried to talk mobs out of violence. But they did not repulse them. Hagan was the first; and he risked the most.

He gave birth to the professional law enforcement custom that eventually did what words and abstract law could not: end lynch mobs as a routine governing force in Florida.

Duty and shame

Hagan put his body and his family between the mob and his prisoner because American law and morality told him that was his professional duty. And he took it seriously. By doing so, Hagan made himself deeply vulnerable to violence and voters alike.

He did not think of it this way, but repulsing the mob was a profoundly political act. Doing his job was a profoundly political act.

It is the most radical example I have ever studied of a person of official power doing a job with no regard to keeping his job or power — not to mention his life. It is without question Florida's bravest, most righteous act of state-sanctioned violence ever leveled against its citizens.

That is probably true for the US, too. Prove me wrong. The righteous police warriors of January 6th and the Capitol Lynch Mob are the only examples I can think of who compare.

Alas, you will not find Peter Hagan or that 1923 moment at the jail memorialized anywhere except my book, Age of Barbarity, and some newspaper clippings from the day. Peter Hagan's grave in Palatka's Peniel Cemetery is the shape — and half the size — of a typical doormat. You will miss it if you don't look very, very closely for it. See below.

Excavating Hagan even a little from Florida's all-consuming historical muck is my proudest and potentially only lasting accomplishment as a writer and amateur historian.

But you will not find the name Peter Hagan within a Florida education History or Civics standard, although no greater Floridian has ever lived.

I’ve adapted this commemoration from an article I wrote about Florida history standards in advance of the 2020 election. But I don’t want to pollute today’s Centennial celebration of Sheriff Peter Hagan’s stand at the Putnam County Jail by injecting willfully-ignorant education gangsters like Ron DeSantis, Richard Corcoran, or Manny Diaz into it beyond just these few brief paragraphs.

“Are you allowed to teach this profound event in Florida schools?” is a question too stupid to ask. So I won’t. I’ll just note that I already have, many times — and will again. The gangsters can do very little about that.

They can do even less about what you choose to read here — or anywhere else. They can’t stop kids or adults from choosing to learn who they are and from whence they came. Stories compel their own existence, independent of any permission, which is why book-banning never works. The best stories, like Peter Hagan’s, demand telling and hearing even after a century of practiced forgetting.

Florida’s governing gangsters and their dark souls would benefit from reading this story. Sheriff Peter Hagan provides the object lesson in what it means for a politician to use official power in the service of public duty and abstract ideas, like justice and due process. He endured deep political punishment and personal consequences for doing so.

This includes his complete erasure from what we remember as a state. But he — and the public — won in the end.

Peter Hagan is the politician and public figure I use to shame myself when I need shaming. More than a few elected gangsters and useless, semi-official hangers-on could use some shame in this state.

Consequences define bravery

I wrote this in Age of Barbarity.

When the mob reared up against Pete Hagan in 1923, rather than surrender to the guns trained on his face, he cracked his pistol stock off the nearest vigilante. Without hesitation. I am in awe of that instinct. I don’t pretend to know how one develops or inherits it.

The sound of righteous violence echoing off that man’s skull is the sound of a great, unknown American making his country’s pretensions real. It was the sound of victory at a time when victories over the mob came all too infrequently. But it came with consequences.

Let's take a look at those consequences, chronologically:

The attack wounded Hagan in his hand — and nearly killed his family. But a few weeks later, in April 1923, a Bradford County jury took just 35 minutes to acquit four men tried in the attack. My great grandfather was part of the unsuccessful prosecution team.

In June 1923, Arthur Johnson, the black man Hagan protected from the mob, was tried and convicted of murder. Johnson was later executed, in what may have been the final Florida execution not carried out at the state prison on Starke. But the trial that Hagan bled to secure for Johnson became very, very important to defeating the Klan a few years later. You can read about that in my book.

On July 12, 1923, Hagan's daughter Gertrude died of a long disease, just a few months after the vigilantes shot into her room at the sheriff's residence in the jail.

On or about February 16, 1924, uniformed Ku Klux Klansmen, including the Gainesville mayor and former police chief, abducted Father John Conoley, founder of the University of Florida's Catholic Center and leader of its drama club, from his church in Gainesville. They beat and castrated him and took him to Palatka. There they dropped him on the steps of the St. Monica's Catholic church parsonage, a few blocks away from the jail.

On February 21, 1924, the Klan held a large parade in Palatka that streamed immediately in front of St. Monica's. The pastor of the First Baptist Church in Jacksonville was the Klan's featured speaker.

The next day, on February 22, one of Hagan's deputies, Israel Fennell, declared that he was challenging Sheriff Peter Hagan in the upcoming Democratic primary election. Fennell's brother Lewis (former Gainesville police chief) is thought to have taken part in the Conoley attack and mutilation.

Not long after Fennell announced his candidacy, Hagan declared in an incredibly brave and direct public statement that he did not and would not belong to the Klan. It's important to remember that the Klan in 1924 was at the peak of its governing power in Florida. It was popular and drew membership from the mainstream civic and religious institutions of the day. I sometimes call it a combination of Hezbollah and Kiwanis. Here's Hagan's statement:

I have recently been asked repeatedly if I am a member of the Ku Klux Klan. To this question I answer, no. I believe I know many members of the Putnam County Klan, and I know them to be good men individually. I do not believe any of them would stoop to organized crime or mob tactics. I am not, and would not be a member, however, of any organization which appears to differ in policies from those who do not belong to its ranks, for the reason that as Sheriff I believe it to be my duty to be perfectly free to serve all the of the people and not an organized part of them; I wish to feel perfectly free to perform my duties without obligations to any order, however high the ideals of such order may be. I have no personal quarrel with the Klan; many of its members are my friends whom I respect and honor, but as Sheriff, I am free, and will remain free to administer the law impartially to all.

In addition, I feel that no that no public servant has the right to ride into office by the hidden help of any secret organization. In my first campaign [in 1916] for Sheriff, I was confronted with the organized opposition of the so-called “Guardians of Liberty,” [an anti-Catholic precursor of the post World War I "revival" Klan] many of its members I knew, almost all of whom now greatly regret their error in becoming members of an organization that proved so injurious to Florida as that one did. Opposed as I was to that order, and knowing its members as I did, yet there is no man who can truthfully say such members did not receive the same treatment from my office as did all others. I cannot control secret organizations and I neither assist or interfere with them so long as their works do not violate the law.

On April 4, 1924, a man named R.J. Hancock entered the race for sheriff, apparently smelling Hagan's vulnerability.

In June of 1924, the good people of Putnam County threw Sheriff Peter Hagan out of office and replaced him with Hancock.

Over the next four years, the Sheriff's Office in Putnam County became a thoroughly criminal enterprise. It openly tolerated and often assisted as drunken vigilante mobs in Putnam County imposed a reign of terror. They attacked and whipped drinkers (yes, drunk mobs punished drinkers); women who were thought promiscuous; black citizens who were considered too defiant; and even a "Greek" man thought to be interested in white women. As many as 80 of these non-fatal lynchings occurred. Hancock's chief deputy, Walter Ivan Minton, who was also a Kludd (chaplain) in the Klan, oversaw many of the attacks. He was referred to as the "whipping boss." At least four people were murdered in connection with these "morality" attacks — two white, two black.

With Hagan sidelined, a multi-racial coalition fought a desperate and dangerous resistance. Women were particular heroes. A white woman named Pearle Casad, who was whipped by a mob on very thin suspicion of promiscuity, was the first person to testify in a doomed state's attorney investigation that hauled in the entirety of Putnam County's law enforcement apparatus. A black woman named Mary Jane Lawson — and close friend of Mary McLeod Bethune — treated victims in her hospital and got information out to the Chicago Defender about the chaos.

The multiracial, anti-woman aspects of these attacks slowly turned part of the Putnam population against Hancock. And in 1926, Gov. John Martin of Florida briefly intervened to threaten martial law in Putnam. But it wasn't until former Sheriff Hagan returned to challenge Hancock and narrowly defeated him in the election of 1928 that the Putnam and Florida Klan was largely defeated. It took popular politics, backed by force, to barely reject the Klan and mob rule as a mainstream political governing force. They forced it to become a potent secretive terrorism force.

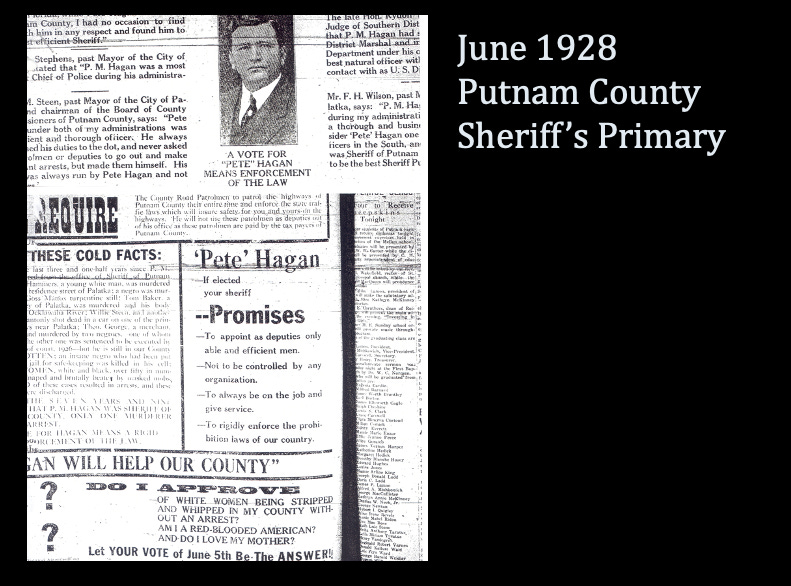

In that 1928 campaign, Hagan did not back up an inch from his record of protecting everyone in his county. He did not apologize for repulsing a mob or repudiating the Klan. He did not "run as a moderate," whatever the hell that means. This incredible newspaper ad sums up his campaign. It is my all-time favorite piece of electioneering.

Under the "Read these cold facts" portion, Hagan honored the victims of the mobs — black or white, man or woman. And then he created this tagline:

Do I approve of white women being stripped and whipped in my county without an arrest?

Am I red-blooded American?

And do I love my mother?

What have you done with your life?

Just two years later, in 1930, Hagan dropped dead of what was most likely a brain aneurysm. He died broke, buried beneath a tiny, nearly anonymous gravesite. The much larger stones of his wife and daughter tower over the flat marker.

And that, dear reader, was just the cliff notes story of Peter Hagan's life and consequences as an elected sheriff.

Peter Hagan risked everything to unify American ideals with action. American Florida did not thank him for it. Rather, American Florida punished him for it in almost every way possible — with his family, his blood, his job, even the record of his very existence.

In absorbing that punishment, and coming back for more, he taught us that the size of greatness can sometimes be measured by the size of the consequences that swallow you and the void they leave behind.

If you're an elected official, a "public servant," or just a person, how do you stack up?

What have you done with your life and whatever power is available to you?

Thanks for doing this research and sharing it. Great information and message.

Thank you for sharing this wonderful history. I’m sure it will give many of us the strength to endure, resist and even seek the good of the current controlling regime of Florida . You are an inspiration