The expendable soldiers of the 1918 pandemic call out to the expendable soldiers of 2020

One of the important subplots of my book Age of Barbarity: the Forgotten Fight for the Soul of Florida is the story of black soldiers in World War I, specifically from Palatka, Florida. Their experience intersected crucially with the earliest moments of the deadliest outbreak of the 1918 flu pandemic.

They almost certainly helped spread the so-called "second wave" through their induction and movements in August and September 1918.

I've put together a modified excerpt about this from my book. It combines material from chapters into a streamlined narrative. It's unfootnoted here because footnotes don't translate over easily into this format; but all of this is documented in the book itself.

I think the story will speak for itself in the era of COVID; and I hope it will make people think about what we mean when we say facile things like: "We're all in this together." We are not. We should be; but we're not. And we never have been.

One day, maybe, when I'm long gone...anyway, that's what I'm fighting for.

These soldiers of 1918 were conscripted into a war on behalf of a country that despised them with the hope of earning a full citizenship that did not come. And then they were viciously punished after the war for believing that serving in the U.S. military had earned them anything at all. It's a terrible national crime; one of our worst. And that's why it's largely unknown. It shook me to learn about it and face it, as someone who unquestionably benefitted from the social structures that allowed it across time.

Today, America is conscripting into a "war" a lot of Americans they didn't realize they were risking the lives to keep households stocked with Fruity Pebbles and pizza -- or, more acutely, fighting to provide care or comfort to our parents and grandparents in nursing homes. They all seem equally as expendable to American power today as the soldiers in my excerpt were. American power certainly seems to consider the residents and staff of Highlands Lake Center expendable.

Friday, the Florida Department of Health's most recent reporting on nursing homes and assisted living facilities in the state shows Highlands Lake Center has had a total of 84 residents and staff test positive for the disease and another 12 -- all residents -- have died.

You can expect COVID to do this to nursing home after nursing home, one-by-one, in the weeks and months to come. You'll have to ask yourself if you think the pace and severity will be impacted by "re-opening," whatever that silly word means.

But as you read my story of the expendable soldiers of Palatka, FL -- and the US -- remember the old saying about history rhyming. And think about how easily the Federal Reserve and federal government could make COVID conscription unnecessary if it wanted to. It's a political choice, just like spending $4.5 trillion to sustain the private wealth of American society's powerful is political choice, not an economic one.

So yes, I'd like very much like to be in it together one day. It's the core of my political project, I would say. But we'll never get there by lying to ourselves and each other.

Every day in this era is a good day to be honest about the wide differences in human experience of power and sacrifice and patriotism.

In that spirit, ask yourself today what lessons of 2020 will cry out to the human crisis of 2122. And what hand will you have in writing them?

Here's the article:

-----------------------------------------

My best analysis of military service cards finds that at least 243 black men of Putnam County served in World War I. That's very nearly half of the 514 total Putnam soldiers, sailors, and Marines that I identified.

When the U.S entered the war in 1917; there were a handful of seasoned, effective all-black combat units. I'm not going to tell their story here. Some deployed; and some didn't, for various political and historical reasons. They're are vital stories that you should know. One of them, the Harlem Hellfighters of the 369th Infantry Regiment was probably the single finest American unit in the war. They're reasonably well-known today. The soldiers I'm about to discuss aren't known at all unless you've read my book.

It wasn't until May 16, 1918, more than a year after formally joining the war, that the United States formulated a clear vision for mobilizing black soldiers drafted into the WWI Army. It came from a War Department memo produced by Col. Col. E.D. Anderson, a top operational planner with the War Department, who was in charge of call-up logistics for Florida. Anderson called this memo "Disposal of the Colored Drafted Men."

This memo largely reflected the white conventional wisdom developed in the early experiences in the war and how the Army should apply it moving forward.

Col. Anderson estimated that the Army would draft 270,000 black men between June 1, 1918, and June 30, 1919, roughly one-seventh of the total number of draftees. Anderson expressed the nub of the military’s thinking on black soldiers.

Only a small part of these 270,000 men can be used for combatant troops. It is the policy to select those colored men of the best physical stamina, highest education and mental development for combatant troops, and there is every reason to believe that these specially selected men, the cream of the colored draft, will make first class fighting troops. After this cream has been skimmed off, there remains a large percentage of colored men of the ignorant illiterate day laborer class.

These men have not, in a large percent of the cases, the physical stamina to withstand the hardships and exposure of hard field service, especially the damp cold winters of France. The poorer class of backwoods negro has not the mental stamina and moral sturdiness to put him in the line against opposing German troops who consist of men of high average education and thoroughly trained...

...It is recommended that these colored drafted men be organized in reserve labor battalions, put to work at useful constructive labor that furthers the prosecution of the war and that when the time comes for sending Quartermaster labor or Engineer Service Battalions overseas, that the men physically qualified be selected from the Reserve Labor Battalions and the required number of labor or Engineer Battalions be formed just as needed for overseas service. In this way, the colored drafted men would be performing useful work that furthers our interest in prosecuting the War from the date they are drafted. White men released by them from day labor work would be free to spend their entire time being instructed for combatant service.

Also the colored men instead of laying around camps accomplishing nothing of value, getting sicker and sicker and in trouble generally, are kept out of trouble by being kept busy at useful work and there is a chance for recommendation of the colored men as the Medical Department can be working on them in the meanwhile, curing them of venerial disease and other diseases and putting them in shape. This will be the first time in their lives that 9 our of 10 negroes ever had any discipline, instruction, or medical treatment, or lived under sanitary conditions and they should improve greatly and at the same time, they will be doing useful work and releasing men for training in combatant service.

Leaving Florida for the pandemic

By August 4, 1918, up to 200 conscripted black soldiers were ready to leave Palatka for induction and training. But this time, the war was in its endgame as the Anglo-French allies, newly refreshed by US power, were pushing the Germans backward in brutal fighting.

The Palatka Times-Herald reported:

The largest increment of colored drafted men for army service from Putnam County will leave Palatka Sunday afternoon at 5 o'clock for Camp Devens, Mass. In this last order, every colored man of draft age in Class 1 has been called, so it is expected that from 150-200 will make the trip from here...

The colored people of the city are planning to give the departing men a good send off, as has been done on previous occasions. This will be the largest detachment to leave the city, and the occasion will be one of general interest.

The call-up of 150-200 men accounted for the largest chunk of soldiers of any race mustered into service at one time from Palatka; but it certainly did not receive the most press or attention. That blurb is all.

By contrast, an earlier send off of 18 white soldiers in September of 1917 produced a detailed and loving account from the same Times-Herald. This group included a soldier named Amos Mack, who I created a fictional persona for in my book. I imagined that he was a logger who hopped a log raft from a camp and reported to the Draft Board, as ordered, on Saturday, Aug. 3, 1918. They shipped out the next day by train for Camp Devens in Massachusetts.

Outbreak

As the men of Aug. 4 rolled north toward Massachusetts, with a “rousing sendoff” lingering in their ears, other characters in my book and Florida's forgotten historical memory converged with them.

After arriving at Devens, those men would share space—within the confines of segregation—with Father John Conoley. The assertive Catholic convert priest, who had been living with the bishop in St. Augustine, volunteered to serve as a chaplain on Aug. 7, 1918. He was assigned to Camp Devens, where he tended to souls and later organized white men into theatrical groups for recreation. Conoley and the Palatka men seem to have entered Camp Devens at essentially the same time.

[After the war, Conoley founded the Catholic campus ministry at the University of Florida. In 1924, uniformed Ku Klux Klan members, including the mayor of Gainesville, abducted Conoley from his church, sexually mutilated him, and dropped him on the parsonage steps of St. Monica's Catholic Church in downtown Palatka, where I was baptized. But that's another story.]

A deadly new arrival soon joined Conoley and the Palatka solders at Camp Devens.

The second wave

The lethal influenza strain of the fall of 1918 -- called the "Second Wave" in many accounts, including the CDC's timeline -- developed from a milder springtime form transported to the trenches and camps of Europe.

It bounced back via boat to the U.S. and other countries. Navy Surgeon General William Braisted traced the arrival of the pandemic flu in the U.S. to August 27, 1918, at Commonwealth Pier in Boston. It hit Camp Devens on Sept. 8. Within a week, it had sickened several thousand troops. Unlike the earlier outbreak of "Spanish" flu in the spring of 1918, this mutated version killed. So within little more than a month of arrival at Camp Devens, Father John Conoley would have found himself attending to a sea of dying men.

The New York Times reported the Devens outbreak on Sept. 15.

The development of 8,000 cases of influenza among the soldiers at Camp Devens led to the sending of a request today to the Surgeon General's office at Washington to detail forty more nurses and ten additional medical officers to the cantonment at once. Three nurses at the base hospital are suffering from the disease. There has been but one death among the soldiers, and that was due to pneumonia, resulting from the influenza.

Lt. Col. McCormack, the Divisional Surgeon, said that with the reasonable care the disease would run itself out. He said the cantonment would not be placed under quarantine because it had been decided at Washington that this would not stop the spread of influenza.

A team of epidemiologists sent to Devens eventually did recommend a quarantine and travel ban for Camp Devens. However, before that could happen, a number of troops left the base for their embarkation point at Camp Upton, Long Island.

It's likely that included a number of the men who had left Palatka on August 4.

Amos Mack's service card, and the cards of several other men, indicate they were assigned briefly to a training battalion at Devens upon arrival at some point in the first week of August. Most likely, they were put straight to work "at useful constructive labor," as Col. Anderson had envisioned.

The Army formally assigned Mack to the 546th Engineer Service Battalion on Aug. 26, the day before the flu arrived at Commonwealth pier. By comparison, white troops training for combat at Camp Devens would receive 14 weeks of training.

Mack's record show he served overseas starting on Sept. 25. It took about two weeks to cross the Atlantic on a troop ship. I can't precisely establish Mack's movements during this time, but every logistical circumstance points to his leaving Camp Devens—along with a number of other Palatka men—just after the flu arrived and before any significant protective measures could be taken.

He may have sailed on the President Grant, the troop transport ship that carried 5,000 black troops to Europe during September, about half of whom came down with the flu during the voyage. At least 97 died and were buried at sea. Many of those who survived, perhaps including Amos Mack, were assigned to unload the bodies not dropped in the ocean on the crossing. The outbreak on the President Grantwas the worst of any troop transport.

While the men of Devens helped spread the pandemic flu in the U.S., it was already raging through the trenches and camps along the fronts in Europe.

"Our Colored Patriots"

Just before the "second wave" pandemic exploded, Palatka held a Liberty Loan parade in its downtown on Sept. 29. It took on the air of celebration as much as exhortation. The Allies were winning.

Windows along the Lemon Street painted up with with patriotic murals bearing titles like “The Knitters for the Allies” and “No Man’s Land” and "Uncle Sam and His Backers."

My great great grandmother, Kate Walton, had overseen the Tableaux Committee that commissioned the window paintings. Her son J.V. Walton, a prominent Palatka lawyer and my great grandfather, held a position on the Putnam County draft board, determining which men had to go an which were too infirm to serve.

The parade, full of attractions making patriotic puns out of the word “bond,” moved along Lemon Street past enthusiastic crowds lining the streets. They cheered or looked on solemnly, as floats with names like "The Bond that Binds Old Putnam" and "Liberty Forever" and "Bonds are our Bullets" rolled. The parade consisted of 19 units, all of which received notice in the next edition of the PalatkaTimes-Herald.

That included the parade's penultimate float, exhibit number 18. It celebrated "Our Colored Patriots." In truth, I have no clear idea what form this took. Paper machier replicas of black people? White people in black face? Actual black Palatkans? I don't know.

But if actual black soldiers and civic leaders road on the float or marched in the parade, as the flu undoubtedly spread quietly around them, these "Colored Patriots" were stalked all night long by the late addition final float. Exhibit 19 of that Liberty Loan Parade was the first Putnam County mass appearance of the Ku Klux Klan.

Although Florida’s new Klansmen had planned to march in this parade for a while, one of the kleagles only formally declared entry the day before. That made the marching men in their pristine robes “the surprise of the evening” as one newspaper put it.

Death in October: names and lives

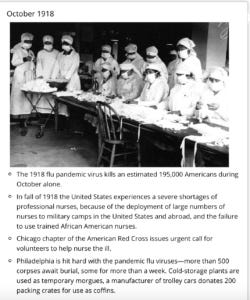

The CDC says the Pandemic killed 195,000 Americans in October 1918 alone.

It seems to have claimed its first Palatka soldier on Sept. 20. Lucius Campbell, who left Palatka with Mack and the others on August 4, succumbed to lobar pneumonia, a common endstate of the flu, at a Pioneer Infantry camp, just more than a month after his induction. He had arrived in Europe on Sept. 4, on an earlier deployment than Amos Mack. The Pioneer infantry units, which saw some actual fighting near the end of the war, were considered somewhat more elite than Amos Mack’s straight labor battalions.

Campbell's death marked the fifth for Putnam County in 16 months of war effort. In the next 31 days, at least eight more Putnam servicemen would die, mostly because of the virulent sickness that destroyed lungs with the efficiency of gas.

On Sept. 25, Clemon Robinson, also part of the Aug. 4 call-up, died of pneumonia, likely at Camp Devens. There's no evidence he ever left the country. September 25, 1918, also marked the birth of J.V. Walton’s youngest child, Lois, his fourth daughter—and my grandmother.

John Caine, a white man, died next, on Oct. 5. Pneumonia. Four days earlier, he'd been promoted to private, first class at his headquarters unit in France.

The next day, Oct. 6, the troop ship Otranto, carrying about 1,000 soldiers to Scotland, collided with the HMS Kashmir near the Bay of Machir. It ran aground and broke apart, killing more than 400 men, including Burroughs Blackmon, of Pomona Park, a village south of Palatka.

A number of the Otrantomen are buried in a military cemetery near the town of Kilchoman, overlooking Machir Bay and the American monument on the Mull of Oa. I don't know if Blackmon is among them.

The Otranto and the President Grantwere the two deadliest troop crossings of the war.

On Oct. 8 and 9th, the flu and its pneumonia killed Andrew Reid and Eugene Russell, both black men. Both hailed from East Palatka. Both men were inducted on Sept. 26. Neither man ever escaped Camp Johnston in Jacksonville, where they were sent from Palatka. In signing off on their induction, in the teeth of the pandemic, J.V. Walton and the rest of the important men on the Putnam County draft board authored their death warrants. Reid lasted 13 days in the army; Russell made it a whole two weeks. [Several men on that draft board, including my great grandfather, went on to play pivotal, at times heroic, roles in defeating the Ku Klux Klan as a popular 1920s governing force in Florida.]

Willie George died on Oct. 14. Pneumonia. He served in the same 546th Labor Battalion as Amos Mack. They traveled to Devens together and crossed the Atlantic together. Like Blackmon, George hailed from the hamlet of Pomona.

Two days later, lobar pneumonia killed Josei Weston, who enlisted in 1916 and had risen to Sgt. Major, senior grade. He had served in combat overseas since February of 1918. He survived the intense fighting of the late summer, only to succumb to the filth it carried with it.

Finally, on October 21, Fernando Meyer of Palatka, who served with the famously mobile Sixth Infantry, was killed in action, probably in support of the second phase of the decisive Meuse-Argonne offensive. However, I can't find any account of his death other than a date on his service card. He was at least the third Putnam man killed in actual combat—and the eighth to die between late September and late October.

Amos Mack managed to evade the microbial bullets whizzing past his body and chopping down his comrades during that month of death. But he was exhausted.

Among many other brutal duties, the Amos Macks of the war buried or burned flu-ravaged corpses, chopped forests of wood, built cantonments, quarried stone, worked under shellfire to repair roads while singing, and unloaded troop and supply ships with names likeLeviathan. I don't know what this Amos Mack actually did. Pick a job. But you can bet he was formally commanded by white work gang bosses who felt contempt for him and that he generally worked hardest for the black corporals that provided the actual leadership on the ground.

And at all times, the Army did what it could to prevent him from mingling with French women. Indeed, an official liaison document between the American and French commands urged the French government to impress upon its people the importance of segregating black soldiers and refraining from lavish praise of their performance. It asked French authorities "not to spoil the negroes."

Some time in mid to late October, the real Amos Mack, not my imaginary avatar, finally ran out of luck, and the pandemic Influenza entered his body. At this point, he could only hope that the flu would not become full pneumonia. If it did, doctors could do nothing for him.

Maybe he was cutting wood at 4:30 a.m. somewhere when he started to feel the fever spike, and his axe began to swing less swiftly. Eventually, the man working closest to him might have noticed the ashen pallor of his face and backed away.

He might have barked to whomever was in charge. "Boss, Mack's getting the flu. Get him off this line."

By the time he dropped the axe and made his way to whatever field hospital/morgue-in-waiting the Army had established for his unit, the fever would have hit 104 or 105. The doctors would have looked at his color and listened to his breathing and known he was doomed. They didn't need to see the pneumonia mucus coating his lungs, or the blood vessels beginning to pop. The evidence of hemorrhage would soon appear in the mess he coughed up. They would have looked at each other, doctor and patient, and known.

"Lie down, boy," the white doctor might have said.

Sacrifices betrayed

Accounts of the war and the flu are replete with incidences of the substandard, indifferent treatment provided to black soldiers, which is hardly surprising. There's no way of knowing if Mack received palliative care or kindness of any sort as he drowned in his own snot and blood. I hope he did.

In any event, it ended for him, bewilderingly far from the St. Johns River, on October 28. Two weeks before the Armistice. Amos Mack became the last Putnam man to die before the fighting stopped, but not the last to die in the war effort. War-related death, black and white, would continue for months.

Amos Mack and the hundreds of thousands of other black soldiers of Great War, did the work that made the war effort possible. They died for it, often horribly. Forget spoiling them. No one has ever really thanked them. Vietnam has a wall. Those Palatka men of the Great War have an undated forgotten plaque. And they won.

Amos Mack seems to have left no children. Whatever he bequeathed went to his sister, Retter, and to a country readying to punish his race for thinking its patriotic sacrifice in World War I had earned it anything.

My book is about how that vicious mini civil war across Florida unfolded in the aftermath of World War I.

Victory and Loyalty

After blowing its whistles, opening up its pistols to the sky, and unwisely reopening flu-shuttered public buildings to celebrate the Armistice, Palatka began to look forward to Thanksgiving and Christmas, the first since 1914 without a war raging in Europe.

And for a brief moment, a few months at most, one could sense the possibilities of a new country in Palatka. We know that Putnam County's soldiers, black and white, took part in a two-day celebration in Palatka, which appears to have included an integrated parade of uniformed veterans on April 26, a Saturday night.

The Palatka Times-Heraldran a sweet invitation to all the county soldiers, black and white, urging them to attend, whether they had uniforms or not. That may have been a nod to black soldiers who served as workers in the U.S. and sometimes toiled in the standard blue overalls of the laborer.

The committee is anxious to have all the boys in line and in uniforms, if possible, and in behalf of the committee I take this opportunity of specially requesting YOUR presence at this time, and if you have no uniform we want you just the same.

Immediately upon arrival in town, the white boys will report to Lt. R.I. Earnest Jr., at Headquarters, (304 Lemon Street) and the colored boys to Lt. G.F. Ellison at Mellon’s School House (105 South 8thStreet) who will register them and furnish each boy with the name and address of the person who will entertain them while here.

Supper will be provided at 5:30 p.m. for the white boys at the Woman’s Club, and for the colored boys at Mellon’s School House.

The Parade will start promptly at seven o’clock and will be under the direction of Major F.E. Jenkins, who will appoint commanding officers.

Everything will be provided for the comfort and pleasure of “our boys” and there will be no charge while you are with us.”

The sincerity of the occasion is palpable. Accounts of the event suggest that black and white soldiers marched in the same parade, although that’s never really spelled out. And perhaps more importantly, although the dinners occurred in segregated facilities, there is no hint of condescension to the service of the black soldiers or even a distinction between their sacrifices and those of white soldiers. That’s very rare in the accounts I’ve read within white newspapers.

The tone of the invitation was bolstered in the Times-Heraldby a huge, detailed, multi-column encomium to the service of black soldiers generally in the war.

Negro Troops’ Bravery Appreciated by Nation

Negro soldiers made a record as fighters in this war as they did in the Spanish American and civil wars. Fighting for the first time on the soil of the world’s most famous battlefields—Europe—and for the first time brought into direct comparison with the best soldiers of Germany, Great Britain, and France, they showed themselves able to hold their own where the tests of courage, endurance, and aggressiveness were most severe.

Colored troops fought valiantly at Chateau-Thierry, Soissons, on the Vesle, in Champagne, in the Argonne, and in the final attacks in the Metz region…

But it didn't last.

The Red Summer of 1919, the bloody Election of 1920, (which should be a Florida and U.S. history standard, but, of course isn't. See about that here.) the incompatibility of full, righteous black political and economic citizenship with what white American power expected was too much.

You should know about 1918-1921; it's a fundamental turning point for the worse in the history of the country. It breaks my heart -- and motivates me.

A monument to The Great War and the Pandemic

By Armistice Day 1921, white Americans in Palatka were erasing black war veterans from the consciousness of the city, as defined by how its white newspapers reported its celebrations. The 1921 ceremony was particularly special in Putnam County. It marked the unveiling of a bronze monument to the county’s dead from World War I.

Although not touted as such, it was also a monument to the 1918 pandemic, which killed a large portion of the names on the bronze.

Gov. Cary Hardee and Florida Speaker of the House Frank Jennings attended the bunting-strewn festivities and gave speeches. A poster/advertisement for the day billed the ceremony as the “Most Attractive Patriotic Program Arranged Anywhere in the State…” and the monument as “One of the Handsomest Monuments to World War Heroes Ever Erected In the State.”

And if patriotism wasn’t enough to gather a crowd, organizers planned a “splendid musical program”, “Football and Battle Royal at Ball Park”, and to raffle off a “Handsome Dodge Touring Car” to lucky winner.

“Joy will be unconfined,” gushed the ad.

Palatka winter resident James R. Mellon, of the Pittsburgh Mellons, donated the monument—just as he later donated land for a new high school and built Palatka’s library. It became the first monument to populate the lawn of the Putnam County courthouse. It’s quite simple and striking even today, with the names of the war dead “cast in immutable letters” into the bronze.

They include all Putnam County black men known to have died in the war effort. But I only know that because I can read them off the bronze plaque and check them against service records.

The newspapers did not list the names; and the act of honoring of Putnam’s war dead for posterity was an entirely white affair, if we judge by the reports of the white newspapers. Nowhere amid the many parade floats, speakers, or onlookers detailed in the accounts does one encounter any record of black participation in the event. No “colored patriots” float, no schoolchildren singing from the colored school. Nothing. Absence. The absence is so noticeable that one wonders how the names of black soldiers even found their way to the bronze.

Today, a life-sized bronze Johnny Reb Confederate statue, built atop a stone pedestal, towers over the center of Putnam County courthouse grounds. It was erected in 1924, three years after the Great War monument.

Yet, it completely overshadows the memorials to the dead of other more recent wars. It is the centerpiece of Putnam's County's temple of law.

It is so much the centerpiece that I couldn't find a single image of the Putnam County Courthouse that actually includes the centerpiece Confederate monument and the much smaller World War I monument, which was there first. In the picture above, it's somewhere off to the front and right. Next time I'm in Palatka, I'll get a photo of it.

A poem carved into the side of Confederate stone honors “the heroism, fortitude, and glory of the men who wore the gray in the sixties”and “their love of country, devotion to principle, and fidelity to the cause they believed was right.”

Back in the late 1990s, as a rookie reporter for the Palatka Daily News, I sat in my little newspaper cubicle thinking up stories with which to meet my daily quota and debating with myself whether to make a stink over the monument and its implications.

I decided not to because I was smug and young and self-satisfied and intellectually lazy.

After all, the Confederate monument was there first, I told myself. Of course the people of the day would want to honor their dead in a powerful way. Why try to revise history? Why dredge up old animosities?

Had I bothered to actually look closely at the monument, or research it even a touch, I might have learned how distorted my own narrative was. I might have pointed out to the public that Putnam’s monument rose six decades after the fall of the Confederacy and three years after the much smaller and less prominent Great War monument. I might have learned that my aunt Susie Lee Walton likely wrote the poem carved into the granite.

Today, the Confederate monument so completely dominates all other courthouse monuments—and so commands the attention of any visitor—that it’s difficult to conceive that it came after the World War I plaque. And it wasn’t just the black men on the bronze whose stories were swallowed by the Lost Cause. More than half the names on the Great War memorial belong to white men. The dashing Confederate figure towers over them, too. Examine Palatka’s World War I plaque today, and you won’t even find the date of its dedication.

I had to look it up in old newspapers.