"Thin love ain't love at all," pt 1: Beloved's track through the trees

I don't remember every plot point of Beloved. But Sethe's sudden forest has never left me. Not in 33 years. How Toni Morrison's visceral reckoning gave me a lifelong gift.

I first read the passage that follows from Toni Morrison’s Beloved — now unavailable, at least temporarily, for any Polk County child to check out from school — when I was in high school. In this paperback, which I still own.

I think I was 17. Maybe 18.

The “bitch” referenced in the first sentence is Beloved herself, the titular ghost of Sethe’s daughter, who Sethe killed as a child rather than return her with a slavecatcher dubbed “Schoolteacher” to Sweet Home, the brutalizing plantation Sethe escaped. The ironies of that plot, with those character names, in this particular moment in time, seem a bit too perfectly constructed.

Beloved, as a work of art, is a visceral reckoning with the consequences and reasons for that act of maternal violence. It’s based on the true story of a fugitive slave named Margaret Garner, or so I recently read.

I had to refresh myself on some of Beloved’s plot details and background.

But I did not need to refresh myself on Sethe’s sudden forest — and her silent split from Paul D. It rocked me as a boy; and it still does so 33 years later, as a 50-year-old man who has now accumulated some living as a husband, father, and citizen; who is rushing, biologically-speaking, toward dotage and death; and who is very much aware I could say the unsayable and unretractable to someone I love.

“And right then a forest sprang up between them; trackless and quiet. “

I found new gorgeous daggers in these few hundred words this time. They comprise, I think, the single most memorably beautiful literary passage I have ever read:

“Your love is too thick,” he said, thinking, That bitch is looking at me; she is right over my head looking down through the floor at me.

“Too thick?”she said, thinking of the Clearing where Baby Suggs’ commands knocked the pods off horse chestnuts. “Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.”

“Yeah. It didn’t work, did it? Did it work?” he asked.

“It worked,” she said.

“How? Your boys gone you don’t know where. One girl dead, the other won’t leave the yard. How did it work?”

“They ain’t at Sweet Home. Schoolteacher ain’t got em.”

“Maybe there’s worse.”

“It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.”

“What you did was wrong, Sethe.”

“I should have gone on back there? Taken my babies back there?”

“There could have been a way. Some other way.”

‘What way?”

“You got two feet, Sethe, not four,” he said, and right then a forest sprang up between them; trackless and quiet.

Later he would wonder what made him say it. The calves of his youth? or the conviction that he was being observed through the ceiling? How fast he had moved from his shame to hers. From his cold-house secret straight to her too-thick love.

Meanwhile the forest was locking the distance between them, giving it shape and heft.

He did not put his hat on right away. First he fingered it, deciding how his going would be, how to make it an exit not an escape. And it was very important not to leave without looking. He stood up, turned and looked up the white stairs. She was there all right. Standing straight as a line with her back to him. He didn’t rush to the door. He moved slowly and when he got there he opened it before asking Sethe to put supper aside for him because he might be a little late getting back. Only then did he put on his hat.

Sweet, she thought. He must think I can’t bear to hear him say it. That after all I have told him and telling me how many feet I have, “goodbye” would break me to pieces. Ain’t that sweet.

“So long,” she murmured from the far side of the trees.

If you read that and sincerely perceive it as part of a pornographic or gross work of art, I pity you. Truly. I don’t know how to help you; and it’s not my place to help you, anyway. I won’t condescend to you like that. I just wish you peace. I’m not here to judge.

But Beloved did not excite or tempt me at 17 with the forbidden erotic possibilities of bestiality practiced by fictional slaves deprived of human intimacy by their owners. I don’t even remember any of those nuggets from the book and still can’t find them within its 320-plus pages. Paul D seems to reference it with his “shame” about “the calves of his youth” in that passage — “How fast he had moved from his shame to hers. From his cold-house secret straight to her too-thick love.”

The far side of the trees

And bestiality does seem an atmospheric part of the set-up for this breathtakingly efficient — 21-word — rendering of a tectonic human experience, which has stayed with me since I read it in 1989 or so.

“You got two feet, Sethe, not four,” he said, and right then a forest sprang up between them; trackless and quiet.

No, Beloved did not imprint fleeting references to desperate animal sex on me; it imprinted the silent impenetrable trees of Sethe’s sudden forest — the consequences of cruelty, the consequences of blithely smothering my shame with someone else’s.

Beloved did this without telling me it was doing it; and thus it was more effective, by vast miles, than any bullshit character education curriculum ever devised to bore children and indulge adults.

How often do men take out their shame on women? How often do humans do that to humans? What happens?

How is it borne? Good lord what an answer Sethe gives:

Sweet, she thought. He must think I can’t bear to hear him say it. That after all I have told him and telling me how many feet I have, “goodbye” would break me to pieces. Ain’t that sweet.

“So long,” she murmured from the far side of the trees.

What women can bear never ceases to humble me.

Billy Townsend: pornographer of bloodless Florida history words

The first two paragraphs of my own book Age of Barbarity: the Forgotten Fight for the Soul of Florida read like this:

Lewis Fennell raised the long curved castration knife to a point where everyone could see it. He’d kept it all these years, a memento of working the livestock on his family’s farm amid the lake hammocks straddling the Alachua-Putnam county line.

Seeing the blade, Father John Conoley pulled against the cords that lashed his hands and feet to the bedposts. And he began to scream as best he could through the gag shoved in his mouth and tightly bound around his head. Blood pinkened the light blonde hair that on most days contrasted with handsome flourish against his black cassock.

It goes downhill from there.

That opening scene becomes an extremely graphic, dramatized account of a real event — the Ku Klux Klan’s 1924 abduction and sexual mutilation of the priest who founded the Catholic presence at the University of Florida.

I’m sure the same people who say they consider Beloved pornography will say they consider my book pornography because of that scene. I, myself, sometimes warn folks about it. But I’ve never yet had someone object to its existence — much less find it pornographic or salacious. I did have the University Press of Florida tell me they couldn’t publish it. So I published it myself. I wanted people to engage vividly the stakes of life in the Florida’s “Age of Barbarity.”

Anyway, here’s a tip, book banners: you’ll find Age of Barbarity in a few Polk County classrooms. In addition to being pornography, book banners, it is the only comprehensive, dramatic history ever written of the rise and defeat of the powerful “revival” Florida Ku Klux Klan that emerged between World War I and the Great Depression. It carries some educational value.

I always donate a copy or two when teachers invite me to talk about it — or about my life as a writer, such as it is. Game on. Go find it, Hannah. And then have Grady Judd arrest me.

A more visceral reckoning than simple repetition of its name

Why did I feel a need to subject readers to the sadistic details of what sitting Gainesville Mayor George Seldon Waldo and former police chief Lewis Fennell — both active Klansmen in 1924 — did to Father John Conoley after they abducted him from his church in full Klan regalia?

I explain that in Age of Barbarity itself as soon as the scene is finished. Note the parts in bold.

If this scene reads like a moment from a neo-slasher movie like Saw or Hostel, it should. To slice into a man’s scrotum as some extra-legal punishment is to behave in the manner of Hollywood’s most sadistic torture porn serial killers. Castration, as a mechanical act on a man, deserves a more visceral reckoning than simple repetition of its name.

And yet, for many years, Father John Conoley’s story did not even merit that level of attention. The first public assertion that the current mayor and former police chief of Gainesville, acting as robed Klansmen, abducted and castrated Father John Conoley in early 1924 occurred almost 70 years after it happened. Historian Stephen Prescott’s account appeared in a 1992 edition of the Florida Historical Quarterly. As valuable a work of history as Prescott and his sources produced, the words abduction and castration and beating mark the limit of the description.

I’ve tried to imagine flayed flesh on the valuable abstractions that Prescott revealed because very little about the non-lethal lynching of John Conoley—and the era into which it neatly fit—is abstract to me.

…

Our key American institutions—including newspapers, universities, legislatures, police agencies, and churches—did little to combat it. In fact, they often justified and encouraged it. There is no evidence that any organization ever reported or protested Father Conoley’s abduction and mutilation to any other organization. No prosecutor ever sought justice for it. The Catholic Church never spoke of it; the records of its aftermath likely lie buried in some double secret Vatican vault.

Ultimately, no Klansman or vigilante of Putnam County or North Florida was ever punished for any act of violence in the 1920s. The only trial ended with a quick acquittal.

I suspect the hooded mutilators of Father John Conoley, if confronted today, would claim some gothic sense of duty drove them to embrace their sadism. Do not believe that. If we imagine what’s involved, physically and emotionally, in removing a man’s testicles against his will, it quickly becomes clear that it requires a special kind of person.

You have to like it.

That kind of man thrived in 1920s Florida. And he did not just brutalize priests. He drank while flogging drinkers. He stripped and whipped and raped women, black and white, whom he considered licentious. He murdered young men, black and white. And quite often, he wielded public office and economic power like weapons. Sometimes he wore hoods; at other times, he didn’t bother.

This man did not die out on his own or grow organically more civilized. His society often rewarded him for his brutality. He was not persuaded by appeals to reason or through measured debate. His conscience did not restrain him.

Instead, this man was stopped—against his will—by other men and women of courage and desperation, and, finally by the slimmest of popular majorities backed with force.

No one struck greater blows in that confrontation than the men and women, black and white, of Palatka, Florida. In the absence of law, it fell to individuals there to face down the mobs and create law.

We should all understand that Hannah Peterson and Steve Maxwell and Jimmy Nelson and the so-called County Citizens Defending Freedom are doing what they’re doing for a simple reason that has nothing to do with books: like Lewis Fennell, they’re doing it because they like it. It feels good. Any pain they can inflict on you excites them. It’s their pornography.

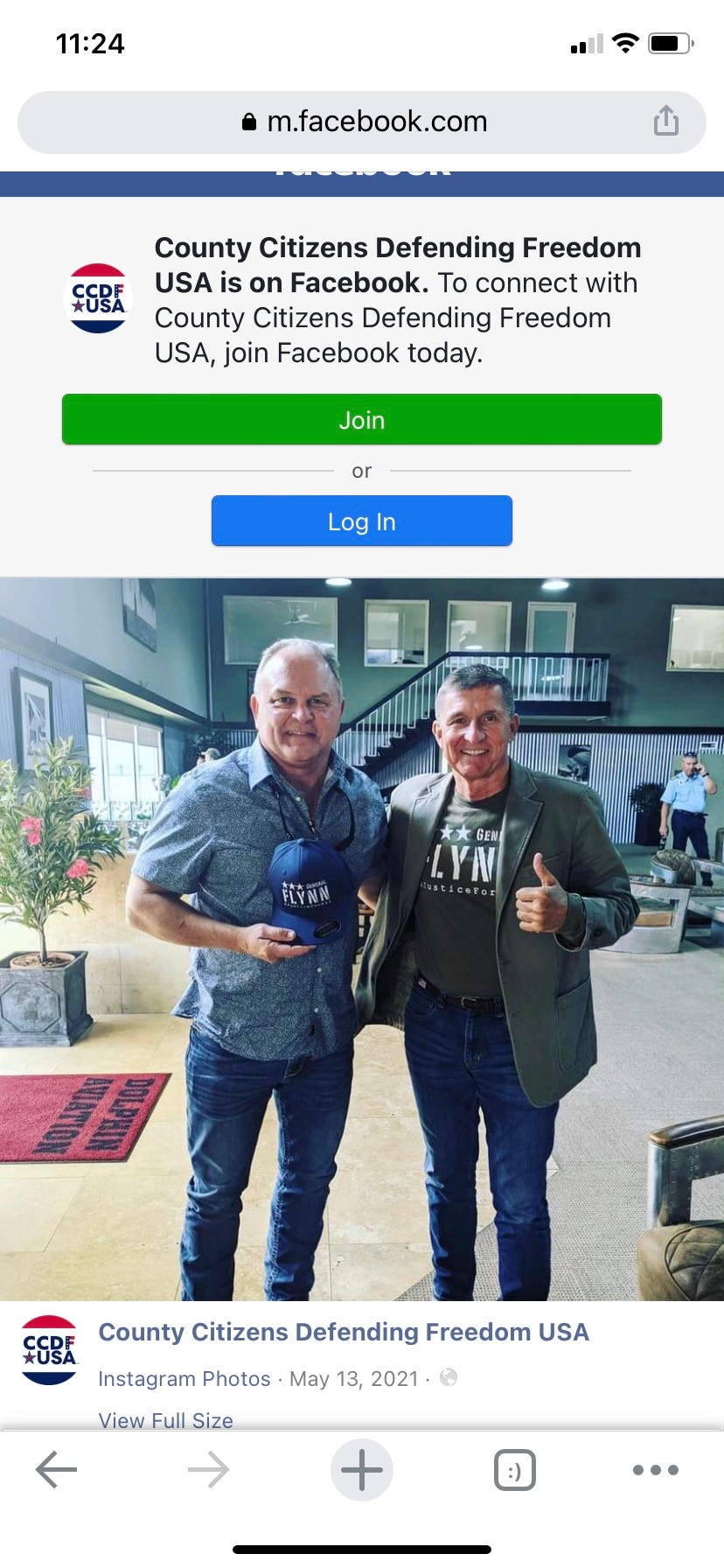

Trust me: if given enough leeway, they will make it to castration. They already celebrate the Capitol Lynch Mob and disgraced Gen. Michael Flynn, who would kill everybody he doesn’t like and seize the country by force if he could — who literally called on the military to overthrow that last election.

And they’re already obsessed with pornography and weird sex stuff.

There is no internal restraint or self-reflection contained in their assertion of power, as their lazy, dishonest, cut-and-paste attacks on literature and humans alike shows. Beloved is no different to them than accomplished charter school principal Donna Dunson or social conservative Christian Republican Mayor Bill Mutz. Or a lonely, vulnerable child portrayed sympathetically in banned book. We’re all libs now.

The name of the target doesn’t matter. They’ve tasted cruelty backed by impunity; and they like it. They live by no rules other than what they can get away with inflicting. They don’t want to share a community with us; they want to douse it with napalm and rule the toxic ashen goo left behind.

Confronting and describing the bloody historical details bound up in bloodless words has helped me understand this. It prepared me well for this era. It has shown me what makes the eternal Jimmy Nelsons and Steve Maxwells and Hannah Petersons tick — and the sense of entitlement to disrupt and dominate your life they’ve inherited.

That’s what literature — and art as a whole — does, too. It makes bloodless words or ideas live beyond the simple repetition of their names. It prepares you and arms you and comforts you.

That’s why it’s under attack.

Thank you for your thick love

I get a lot of “thick love.” Far more than I deserve, when compared to people who could use much more of it. My life has been filled with it. I hope I have given some of it back to the people in my life and community.

Much of that thickness is bound to literature. And I come back to a number of favorites pretty often.

And in that very moment, away behind in some courtyard of the city, a cock crowed. Shrill and clear he crowed, recking nothing of war nor of wizardry, welcoming only the morning that in the sky far above the shadows of death was coming with the dawn.

And as if in answer there came from far away another note. Horns, horns, horns, in dark Mindolluin’s sides they dimly echoed. Great horns of the north wildly blowing. Rohan had come at last.

I heard that first from my Dad’s mouth when was about 6 — and then read it again and again as I grew — before a film could compete with it. My kids heard it first from me.

“You have to mean it, Potter.” And:“Try for some remorse, Riddle,” I share with my daughter in a different generation of fantasy, even though she accuses me of skimming the books.

I read the atheist Camus animate the humanity of the austere, judgmental Catholic Father Paneloux in The Plague because of European Studies 100 at Amherst College. I did so under the demanding Germanic accent and guidance of Prof. Elizabeth Trahan.

They had already seen children die — for many months now death had shown no favoritism — but they had never yet watched a child’s agony minute by minute, as they had now been doing since daybreak. Needless to say, the pain inflicted on these innocent victims had always seemed to them to be what in fact it was: an abominable thing. But hitherto they had felt its abomination in, so to speak, an abstract way; they had never had to witness over so long a period the death throes of an innocent child. In the small face, rigid as a mask of grayish clay, slowly the lips parted and from them rose a long, incessant scream, hardly varying with his respiration, and filling the ward with a fierce, indignant protest, so little childish that it seemed like a collective voice issuing from all the sufferers there. Paneloux gazed down at the small mouth, fouled with the sores of the plague and pouring out the angry death-cry that has sounded through the ages of mankind. He sank on his knees, and all present found it natural to hear him in a voice hoarse but clearly audible across that nameless, never ending wail: “My God, spare this child!” But the wail continued without cease.

Professor Trahan would not remember my name or my existence if she’s still alive. But she loved thickly enough to embarrass us if we didn’t do the reading. And it was the best college class I ever took — the only A I ever really earned or give a shit about today. I read and wrote about The Plague again in March 2020, with great satisfaction and comfort.

I regularly fight through Intruder in the Dust’s 30-page-plus raggedly ephemeral portrait of the mass inner life of a Mississippi lynch mob collapsing under its own feckless wrongness — wrong, as in incorrectly roused by a white guy killing his brother and framing Lucas Beauchamp.

Yeah, this sequence contains the Confederate nostalgia Gettysburg passage Faulkner made famous — For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two o'clock on that July afternoon in 1863 …

But it ain’t really nostalgia.

And I don’t think many people who have read that quote, in isolation, understand it’s a tiny island of monumentism poking out of a massive eddying narrative river of shame and rationalization defined ultimately by this …

“They ran,” he said. “They reached the point where there was nothing left for them to do but admit they were wrong. So they ran home.”

And this…

What sets a man writhing sleepless in bed at night is not having injured his fellow so much as having been wrong; the mere injury he can efface by destroying the victim and the witness but the mistake is his and that is one of his cats which he always prefers to choke to death with butter.

And what, if anything, does a whole-town mob owe Lucas Beauchamp for its feckless wrongness — for coming so casually close to inflicting semi-official mutilation on a stubborn old man? With what butter will they choke him in penance? There is no answer; but there is debt and payment. Lucas insists on paying the indignant and shamed old lawyer who didn’t believe he was innocent — until a young nephew figured it out — and the book ends like this:

“Now what?” his uncle said. “What are you waiting for now?”

“My receipt,” Lucas said.

You could merge slavery’s Beloved and Jim Crow’s Intruder in the Dust — stylistically, historically, lyrically — and tell one unified story.

They shadow each other likes mimes. Just move Sweet Home to Yoknapatawpa and make Schoolteacher an ancestor Gowrie; or make Lucas Beauchamp into Sethe’s grandson. The stream of opposing consciousnesses could speak to each other intimately, within the same work of art, within the American forests of power and vulnerability and race and love and shame and time.

But they don’t. Not yet. They’re still parallel books, separated by dense trees. And the Gowries of the moment want to inflict pain on one consciousness because they can — because one consciousness wields more raw power in 2022 America. Every ban, every prohibition, every monument is an act of power — not taste, or aesthetic, or child-protection.

By contrast, reading and writing, with the sincere purpose of engaging human experience honestly, is a thick act of love, for oneself and for others. Thick love led me to both Beloved and Intruder in the Dust. It’s the reason I wrote my own books — the reason I write all of this stuff.

A girl I liked was reading Beloved in the same Palatka High School AP English class in which my dear Aunt Sophie introduced me to Zore Neale Hurston and James Baldwin. My family told me the root of the stories I chased down in Age of Barbarity. The dead people I met in books and newspapers and came to love who populate Age of Barbarity led me to Intruder in the Dust — because the Whiggish uncle lawyer reminded me of my great grandfather. And I guess the nephew reminded me of braver version of boyhood me.

Sethe does not remind me of my great great grandmother. I don’t inherit the residue of her consciousness. Instead, Toni Morrison gifted it to me on a page. I’m so grateful for that thick love. And I recognize the universality of Sweet, she thought. He must think I can’t bear to hear him say it.

That’s why Beloved will survive Hannah Peterson. That’s why Beloved will survive anything as long as it a matters to the consciousness of human beings.

It cuts tracks through the forests we grow between us.