Invasion of privacy, part 2: Kate Walton's notion of "individual sovereignty" rejects 6-week forced birth - and much more

My beloved great aunt, the "mannish" mother of Florida's right to privacy, had much larger moral ideas in 1943 than "informational solitude."

See Part 1 below. It’s my account of last week’s Supreme Court hearing on whether Florida’s constitutional amendment guaranteeing a right to privacy protects women from forced birth.

Images may cause this article which is part 2, to truncate in email. Click through to the actual site if you need to.

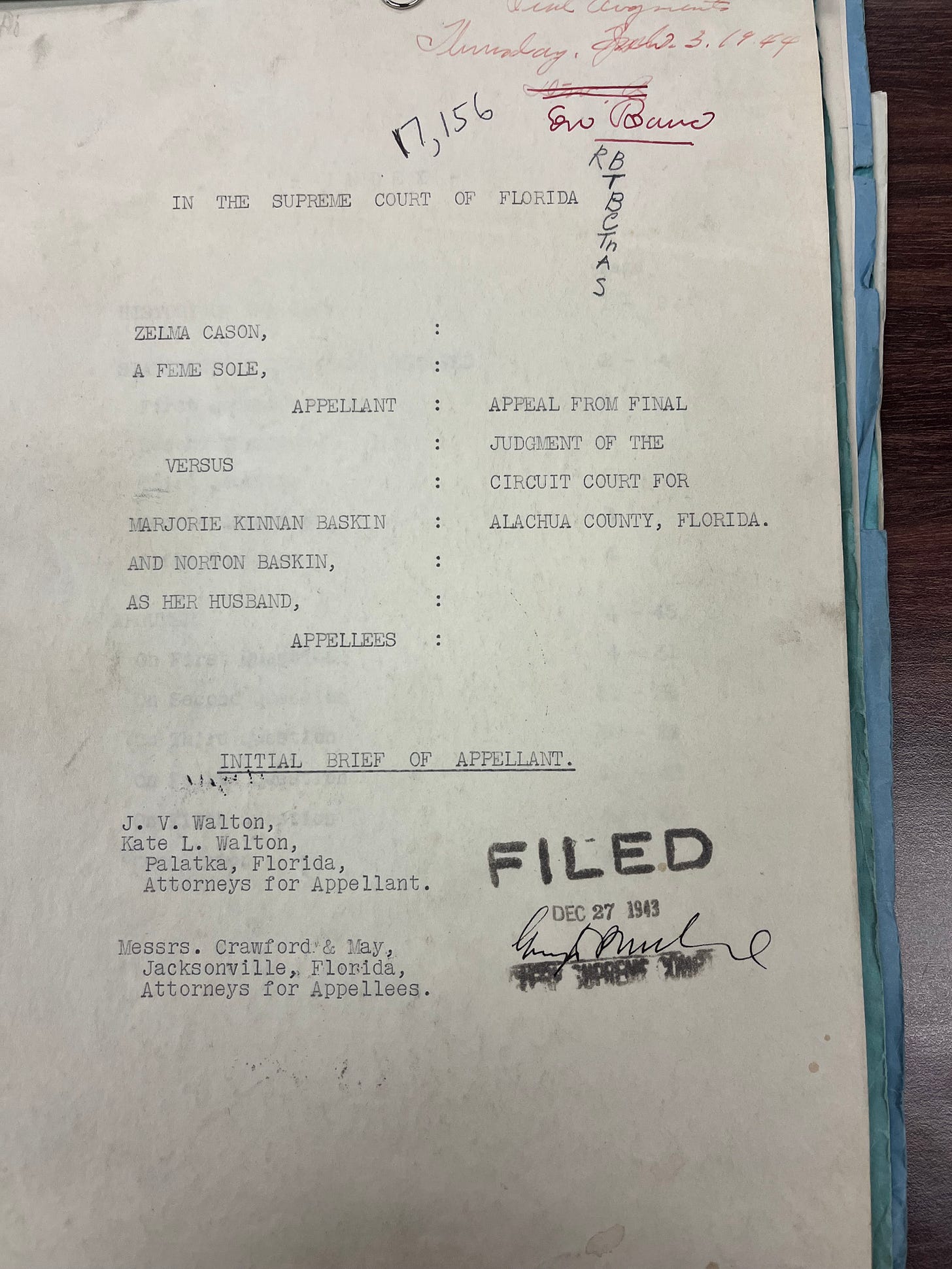

On December 27, 1943, Kate and J.V. Walton — my great aunt and great grandfather —filed this brief with the Supreme Court of Florida. It would lead to the establishment of an enforceable right to privacy in Florida’s common law — which is the body of civil law not explicitly spelled out in statute, but created by judicial precedent.

The case is known as Cason vs. Baskin, in which Zelma Cason sued famous Florida writer Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Baskin for her sexually-charged portrayal of Cason in the quasi auto-biographical book Cross Creek. I’m writing a book about the case. Here is a fun trailer of sorts about my book.

Zelma Cason did not give Marjorie Rawlings permission to publish a description of her using her real name; and she objected to the intimate and presumptuous callousness with which Marjorie described her. Kate and J.V. Walton took up her case as the plaintiff’s lawyers. They alleged both libel and something new for Florida — invasion of privacy. The concept of an enforceable right to privacy came from a legal paper published by future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and his law partner Samuel Warren in 1890.

Kate Walton’s brief urged the Florida Supreme Court to recognize a state right to privacy for the first time. It appealed a lower court’s dismissal of her case and aimed to establish invasion of privacy as cause of action in state civil court.

Despite J.V. Walton’s name coming first on this brief, Kate Walton did almost all the actual work and writing — as she did for virtually every aspect of Cason v. Baskin, except for the 1946 trial questioning and argument.

While the cause of action grew from a very specific act of unwanted publicity, Kate Walton’s theory of “privacy” was far far broader than “informational solitude,” a term we’ll come back to in a moment.

“Individual sovereignty”

Kate Walton opened the argument portion of brief by explicitly connecting the right to privacy to the expansive moral purpose of World War II, which was raging at the time she wrote and filed the 1943 brief.

As an unmarried woman in her late 20s, Kate had desperately tried to join the formal American war effort — as a lawyer, ambulance driver, or anything, really. She was rebuffed at every turn, mostly by men telling her she needed to help take care of her extended family at home.

It’s silly to say to say Marjorie was Germany to Zelma’s Poland for Kate Walton; but it’s impossible to overstate, in my view, how much she saw Zelma’s defense against invasion as an act of moral, wartime patriotism on behalf of vulnerable individuals abused by power.

Repelling Marjorie Rawlings was the next best thing she could do to strike a blow at Hitler. Note the part in bold in this excerpt — and the emphasis on “individual sovereignty” and “personal freedom.”

It is peculiarly fitting that the right of privacy should have been first recognized and integrated as an actionable right under the common law in the United States, for this right is a necessary corollary from the principles of individual sovereignty and of maximum personal freedom under laws which are corner stones of our theory of government; and it is not inappropriate that this cause should come before this Court in a year of war when the very status of man is in issue, for it is with the dignity of man as a free-willed individual that the law of privacy concerns itself, and, in the last analysis, we were constrained to wage this war, not for numbered freedoms, not to assert the superiority of one form of government over another, but by an urgent need to maintain our concept of the equality of man and of his status as a free individual.

She went on to say the following about how Marjorie Rawlings abused her power as a famous writer to violate Zelma Cason’s personal sovereignty, which is something different and broader than mere protection from publicity.

An individual may not use another so. The self-evident truth that "all men are created equal” forbids it. Men are equal under laws and are equal in quality of individual rights. Each man is absolute sovereign in his own individuality and personality. This is the dearest tenet of free-willed man.

What truly drove Kate Walton, legally and morally, was Marjorie Rawlings’ invasion of Zelma Cason’s personal sovereignty. “Privacy” was the legal concept available to her; but Kate Walton saw Cason v. Baskin as a case about the aggressive, predatory behavior of power — much more so than a case about media or information.

A man or a mother

When I refer to Marjorie’s description of Zelma as “sexually-charged,” I’m using the word “sex” in three ways — actual sex, sexuality, and what we would call “gender” today.

Marjorie publicly assessed Zelma in each of those three dimensions of sex in just one paragraph in Cross Creek. She got even more detailed on the witness stand during the trial in her observations of Zelma’s sexual identity. Marjorie’s letters and general writing suggest she thought a lot about sex, in all its dimensions, which my book explores. But here is the actual, privacy-invading passage from Cross Creek:

Zelma is an ageless spinster resembling an angry and efficient canary. She manages her orange grove and as much of the village and country as needs management or will submit to it. I cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother. She combines the more violent characteristics of both and those who ask for or accept her manifold ministrations think nothing of being cursed loudly at the very instant of being tenderly fed, clothed, nursed or guided though their troubles.

Marjorie dropped that on Zelma — with whom she had endured a brutal, emotional, and unrepaired falling out about a decade earlier — in a best-selling the “Book-of-the Month Club” semi-autobiography. Zelma and Marjorie were not friends anymore when this was written and published. And yet, Marjorie seems to have expected Zelma’s gratitude for that portrayal — for that invasion of her personal sovereignty. Marjorie likely considered it a kind of peace offering.

But imagine yourself as the famously temperamental Zelma, defined for the world as neither man nor mother in 1942 by a one-time close friend you think betrayed you back in 1931. Would you be grateful this great woman included you like that as a funny anecdote in the story of her Florida life?

As if “man or a mother” and “spinster” weren’t blunt enough commentary on Zelma’s relationship to sex, Marjorie helpfully clarified further under oath during her trial. Note the part in bold:

As I said, I had to sit down and think, now how do you describe Zelma? What is she? She is not a married woman. I could not describe her as an old maid, because I think of an old maid as a woman who is not married because she has not had an opportunity. Zelma had always had admiration from men and opportunities to marry. So I thought “spinster” was the only term. I noticed the other day when Woodrow Wilson’s daughter died it described her as a “spinster.”

What do you think Marjorie is calling Zelma there? Frigid shrew? Lesbian? And yes, “lesbian” was very much in Marjorie’s personal vocabulary. She used it, with great disdain, in a 1943 letter (unrelated to the case) she wrote to her husband as the Cross Creek case was moving through the courts. She knew what she was implying when she said that to the jury.

The same species of ridicule and obloquy

Near the end of the 1943 Cross Creek brief, Kate Walton wrote what was obvious in its time.

The third and fourth sentences charge plaintiff with having the more violent characteristics of a man, and it should be borne in mind that a masculine woman is regarded with the same species of ridicule and obloquy that is bestowed upon an "effeminate" man. It is neither natural nor desirable for a woman to have “the more violent characteristics" of a man.

Like Zelma, Kate Walton was neither man nor mother in 1943 — nor would she ever become either. After the Cross Creek trial in 1946, the Miami Herald published a female college student’s eyewitness account. She wrote that Kate’s “general appearance was mannish, her countenance, resolute.”

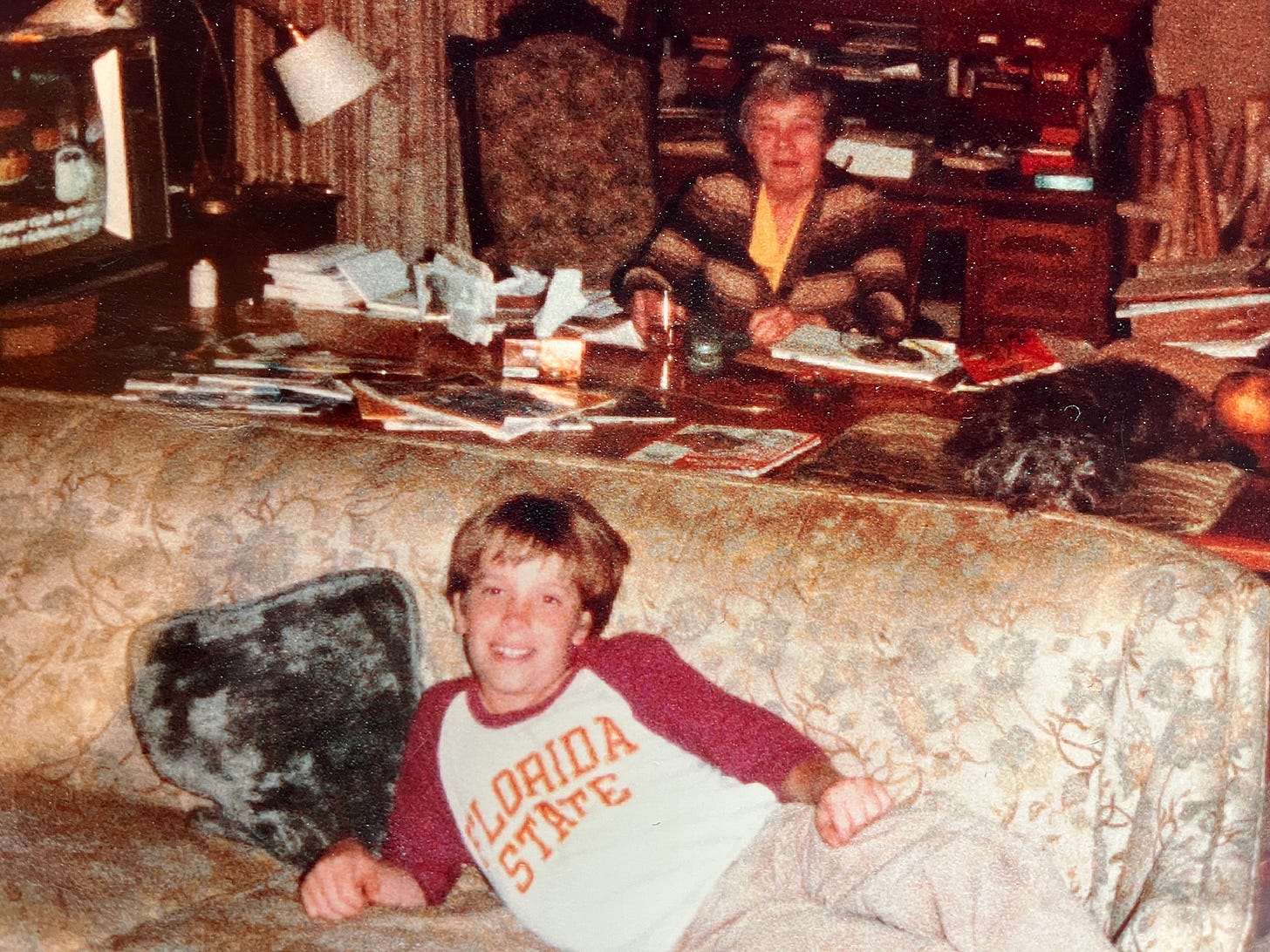

I knew and deeply loved my much older Aunt Katie as a little boy in late 1970s and early 1980s Palatka. Her unique, brusquely doting, “mannish” femininity was an irresistible part of it. I cherish every moment I spent with her catching cane-pole bream from her St. Johns river dock or picking her oranges or riding with her to pick up barbecue sandwiches from her local dive bar.

So I wasn’t surprised to read decades later that another woman described Kate’s general appearance as “mannish,” even when she was a younger woman. I’m sure she got that often — especially as one of the first killer female litigators in the state of Florida. Even her legal writing has a bit of a Hemingway stylistic vibe to it.

I was surprised by the undated photo of her as young woman I shared above.

It’s the only image or memory of her I have that conveys conventional femininity. I wish I knew the story behind it. Does it reflect a short-lived, conscious effort to conform to expectation for the sake of her professional ambition? Or is this pretty, at ease, 30-ish Kate Walton as authentic to her personhood as the mannish, pioneering lawyer others saw and the earthy, cigar-chomping, thunder goddess of niece and nephew-spoiling that I loved?

I only know that Kate Walton eventually married one of her father’s friends, a German emigre aristocrat 30 years older than her, not long after the Cross Creek case. She was widowed within a decade in her late 40s, before I was born. I won’t hazard any guess about her private, amorous life beyond that.

I’ve only hazarded this much for a specific reason — to provide context for this letter that J.V. Walton, Kate’s prominent father and Cross Creek co-counsel, wrote in January 1944. Note the bold:

When Miss Cason first came to us, I was quite hesitant in advising her to enter into litigation, but my daughter immediately formed a favorable impression of Miss Cason and readily appreciated how she felt; and as she looked into the law and discussed the case with me, I became equally interested. Now it is really something more than an ordinary lawsuit to us.

To comment in public at anytime on person’s masculinity or femininity remains a charged invasion of sorts today. Imagine it in 1943 — as the defining aspect of your sexual identity — shared casually with the world, as an object of fun, by the most famous woman in Florida.

Imagine the Miami Herald declaring you “mannish” for all its readers.

I submit to you that the personal sovereignty of women — the right of women to be who they are, sexually and otherwise, and then left in peace about it — was a crucial engine of Kate Walton’s battle for privacy and against invasion — right there with World War II.

So how do you think Kate Walton — the “mannish” mother of Florida’s right to privacy — would have reacted to the idea that every miscarriage is a potential crime scene requiring investigation? Do you think she would support a Jennifer Canady/Grady Judd pregnancy registry and tracking system?

Do you think she believed every woman’s relationship to sex and her body — in all its dimensions — should be dictated by state power?

“Informational solitude” vs “decisional autonomy”

The constrained right of privacy Kate Walton won for Floridians in the Cross Creek case did not affect what the government could do to its citizens. It was enforceable only against private acts using civil courts — where the “common law” most effectively dwells.

In 1980, 60 percent of Florida voters approved a privacy constitutional amendment, which expanded Cason v. Baskin protections against the private power of Marjorie Rawlings to the public power of the government.

Since then, legal precedent and adjacent referenda have held that the amendment protects a woman’s right to end a pregnancy in Florida and prevents the Legislature from making it illegal.

Last Friday, on Sept. 8, 2023, the Florida Supreme Court heard arguments questioning if the amendment does, in fact, protect women from forced birth the imposed by the Legislative and Executive branches of the state.

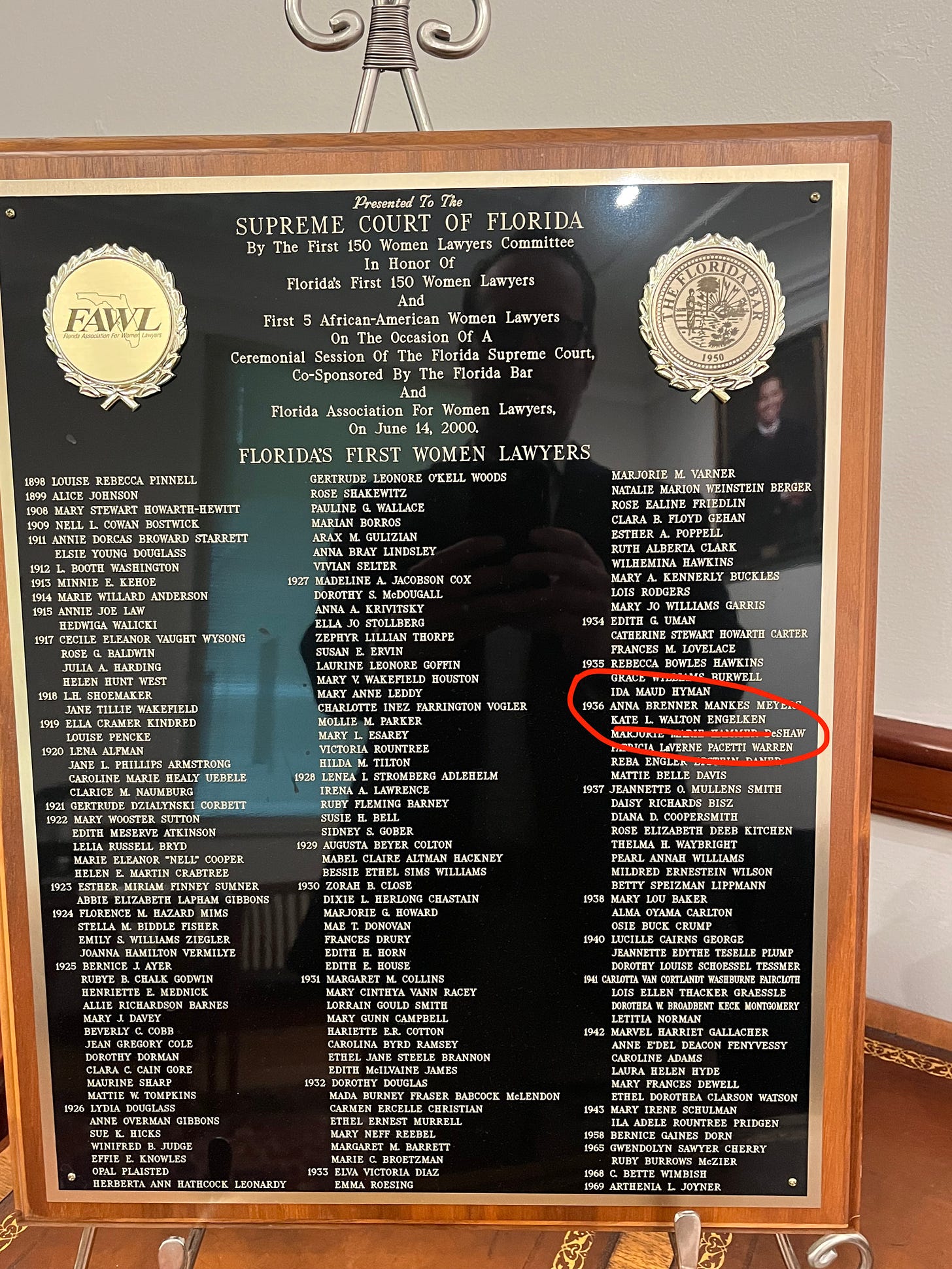

Fittingly, Kate Walton and Cason v Baskin were both on hand for the hearing. This plaque honoring the first 150 women lawyers of Florida stands on display in the “Lawyers Lounge” inside the court building, not far from the actual courtroom.

And lawyers for the state cited Cason vs. Baskin twice in their brief arguing that the constitutional amendment only protects “informational solitude.” Here’s the core of their overall argument. Note the parts in bold:

Those words, dating from Justice Brandeis in 1890 to the Tampa Tribune in 1980, protected informational solitude, not decisional autonomy. That, after all, is how most ordinary people understand “privacy,” not in the specialized sense of the word—favored by the cognoscenti steeped in Roe and its progeny—that includes all manner of personal decisions. It was, in fact, not lost on Section 23’s framers that activists might misappropriate those words to constitutionalize controversial issues like intimate relations and drug use. They thus took care to explain that decisional autonomy was “not what they had in mind at all.” App. 6. Section 23’s goal instead was to keep “Big Brother” in check.

This is silly.

Ordinary people do not think of privacy as defined by media. After all, a “privacy” fence does not protect a homeowner from reporters. It protects private acts from the prying eyes of anyone who might want to intrude on the personal decisions you make in your own home. Indeed, many invasions of “privacy” are already criminalized — stalking, peeping toms, etc.

Moreover, Brandeis and Warren’s seminal paper assumes an already existing right of physical privacy defined by the sovereignty of one’s home. They were expanding privacy protection beyond the home to abstract notions of the self.

The common law has always recognized a man’s house as his castle, impregnable, often, even to its own officers engaged in the execution of its commands. Shall the courts thus close the front entrance to constituted authority, and open wide the back door to idle or prurient curiosity.

There is no question to me that Kate Walton started her expansion of the Brandeis/ Warren privacy argument with “informational solitude” because that was the nature of the sovereignty invasion before her. But she did not intend legal personal sovereignty to end with constraint on media power. She intended it as a check on all abusive and intrusive power on behalf of the people most vulnerable to it.

She intended to make one’s castle portable.

Feel the indignation of this again:

An individual may not use another so. The self-evident truth that "all men are created equal” forbids it. Men are equal under laws and are equal in quality of individual rights. Each man is absolute sovereign in his own individuality and personality. This is the dearest tenet of free-willed man.

That is not about narrow standards and practices of publishing.

Of course, this discussion is all largely academic. The abstract legal debates of forced birth are meaningless. The quest for forced birth has always been about power, not law or “life.” Thus, the outcome of last week’s hearing is a foregone conclusion. The Florida Supreme Court has corrupted itself too far to stop now. A dictatorship that blinks dies. I don’t think they’ll blink.

Six week forced birth is coming — against the will of 75 percent of Floridians, according to polls. Its implementation will create an invasion of privacy of unparalleled brutality for all Florida women.

And today, as I noted in part 1, the former “pro-lifers” are terrified of that.

They’re terrified of taking any personal or moral responsibility for the brutal and deadly forced birth power they’ve won by corrupting the courts. That’s a pretty dark irony.

Kate Walton would have deep contempt for their moral cowardice — which she did not share. She never feared or ran away from the behavioral and professional requirements of her “beliefs.”

The civilized substitute for the horsewhip

Pro-lifers fear both the visceral brutality of carrying out mass forced birth and the personal humiliation of openly retreating from it back to moral and legal sanity. That’s why they’re hiding.

Unlike them, Kate Walton never ducked the implications of her beliefs about personal sovereignty.

She understood clearly what bringing an invasion of privacy claim against Marjorie Rawlings required her to do: inflict sustained pain on the most famous woman and culturally powerful person in Florida in the mid-1940s.

The fortunes of the case swung back and forth radically between 1943 and 1948. Zelma and Kate lost, then won, then lost, then won, then lost again — sort of. It finally ended in a rather bloody draw that wounded everybody involved in it. In the end, the Supreme Court ruled that Marjorie invaded Zelma’s privacy, but that Zelma was only entitled to $1 plus court costs in damages. Everybody thought they lost.

But Marjorie and her Florida fans lost the worst.

Marjorie lost on the principle, which was crushing to her. But even more than that, Kate Walton’s unrelenting willingness to inflict public pain on Marjorie through law and argument essentially drove her from Florida and ended her career as a successful writer.

It’s entirely appropriate to question whether that sentence fits the crime. I’m not sure it does. But proportion was not the point. Deterrence was.

One cannot argue this focused pain did not have a clear deterrent purpose and effect. It proved that the unjust invasions of power could be made to hurt powerful individuals themselves, personally. If nothing else, writers across the state and country learned to think twice about using an old frenemy’s name in gratuitously personal ways for money.

For example, here is Kate Walton, still fighting in 1948 for a reconsideration of damages, explaining to the Supreme Court the value of pain in deterring power and discouraging invasion. Notice how absent “informational solitude” is a limiting concept in stopping the invasion of “self-sovereignty.”

In holding that plaintiff suffered only nominal damage as a result of defendant’s tort on a finding that plaintiff had proved no loss of friends or respect in the community and no injury to character or reputation, the Court overlooked and failed to consider the nature of the injury for which redress is sought in an action of the right of privacy.

The primary injury is the derogation of the equality of the victim, the unjustifiable use by a tort feasor of the person or personality (or incidents or evidences thereof) of another to serve the purposes of the tort-feasor, without the consent and against the will of the victim.

An action for violation of the right of privacy, sometimes called the “civilized substitute for the horsewhip,” is necessarily punitive in its nature. It seeks redress for the inner feeling of outrage and humiliation caused a self-respecting person by the wrongful act of another using, exploiting or exposing the former, against his will; the compensable injury is subjective, is to the spirit, the dignity, the cherished self-sovereignty of the individual.

Does that concept and approach to confronting power sound familiar to anyone who has read my “citizenship writing” work of the last decade or so?

I did not set out to emulate my Aunt Katie’s approach to combatting power’s unjust invasions. But I have discovered, through the young woman who burns at the heart of the Cross Creek case, that I can locate my instincts and work in a small way within her tradition of moral thought and writing and behavior.

You can likely guess what that means to me.

The humblest as the greatest

As you can see, the Cross Creek case is far more relevant to the war over forced birth and personal sovereignty than most, if not all, Florida lawyers, historians, and citizens understand.

And I suspect that’s how I accidentally ended up attending last Friday’s Florida Supreme Court heard arguments in Tallahassee.

My Aunt Katie is famed among family and friends for what we’ve experienced as her transcendent powers and presence — both during her life and after her death. Thus, the string of personal coincidences that put me at the Supreme Court on Sept. 8 and helped me find Kate Walton’s still-existing, officially-filed 1943 Supreme Court brief (I’ve long had copies) make it hard for me to consider them coincidences.

You may think my perception absurd and laughable; but I don’t care what you think.

I do care what Aunt Katie thinks.

She never talked about the Cross Creek case because she largely considered it a painful failure. I wanted to understand why — and that meant getting close to her personhood as a younger woman in a way a worshipful little boy couldn’t with his beloved elderly playmate. So when I started this project years and years ago, I worried that her attachment to “privacy” might put me at odds with her spiritual presence.

I don’t worry about that anymore. I think I understand now what privacy and its invasion meant to her. And I have enough personal spiritual evidence to convince me that my Aunt Katie wants Kate Walton’s invasion of privacy story told. I think she may find it useful for advancing her cause from the great beyond.

And with that in mind, I think it’s best to give her the final word on that cause. This is from the 1947 brief that led the Florida Supreme Court to overturn the 1946 trial verdict and rule that Marjorie Rawlings invaded Zelma Cason’s privacy.

Counsel conceive that the concepts that all men are equal under the law, entitled to equal justice; and that the courts shall not respect persons in judgement, are not empty words to palliate the great mass of unimportant obscure men, but are the life, the reason for growth, the very essence of our democratic civilization and system of jurisprudence.

We think further that to impugn these concepts is not only to derrogate the principles of our government and of our system of jurisprudence but is to profane mankind, for not only were famous authors created in the image of Diety but each of us, the humblest as the greatest.

Excellent defense of privacy and a woman’s right to be free of governments invasion of her body. I did not realize you had a personal stake in being at the talk in Branscomb last night. I hope when your book is published you have a chance to speak in that and similar forums. This is very important work you are doing. I hope it is shared with a wide audience.

Bobby Baum