My cousin Peter, the Black Confederate slave who was neither, part 1

This family story, a chapter from my in-progress book, is best way I can respond to Ron DeSantis' tired "slavery was VoTech" troll and the Nashville bro's thirsty-for-attention lynching song.

Here is Part 2 of Peter Vertrees’ story. But read Part 1 first.

As I’ve noted here before, I’m about halfway through writing A Man or a Mother: Kate Walton, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and the fight for self-sovereignty in American Florida. It’s my decade-in-the-making biography of the almost famous invasion of privacy lawsuit against iconic Florida writer Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.

My beloved great aunt Kate Walton, arguably Florida’s first true female litigator, who I knew and adored as a little boy, teamed with her prominent father Judge Vertrees (J.V.) Walton in 1942 to represent the plaintiff Zelma Cason. The case more or less ended in a draw. But Kate Walton established an enforceable right of privacy in Florida — and essentially killed Marjorie’s career as a Florida writer. What follows is part 1 of an extended chapter from the book that I’m very proud of. Its purpose in the book is to contextualize Kate and J.V. Walton a bit — to show readers the family mythologies and lies and beauties that shaped them.

But more importantly, this chapter stands alone as the story of Rev. Peter Vertrees, American and Tennessean. And it corrects some of the romantic historical slander laid upon him by Confederate nostalgists with his complex, tragic, and beautiful story. Jason Aldean is much too dumb to even sing a song somebody else writes about Peter Vertrees.

This may truncate just slightly in email. So click through if you need to.

Sons of the masters, mothers of the bound

Judge Vertrees (J.V.) Walton was my great grandfather. He was a lawyer named for a judge, but never a judge. His great grandfather on the Walton side — and then his sons — became very rich owners of 400 or more enslaved people in western Alabama, not terribly far from Selma, after migrating there from North Carolina in the first half of the 19th century.

It’s likely that they settled on land that Andrew Jackson and the United States of America took from factions of the Creek Nation.

Alabama empire

J.V.’s grandfather, John William Walton, inherited his slave empire from his father William in 1849 at age 32. He maintained and grew this enterprise of flesh until the Civil War. Just south of modern day Greenesboro, Alabama, you can drive for seven miles on Highway 25 and see nothing but one-time Walton family wealth on either side. Here’s part of it.

Evidence – unconfirmed family stories mostly – suggest John William Walton was an anti-secessionist who trained at least some of his slaves in skilled trades. He sold off his land and left Alabama under scalawaggish duress following the Civil War. Various oral and family histories say many of his former slaves followed him. The Walton family eventually settled outside Nashville, in Gallatin, Tennessee.

There his son, John Norfleet Walton, met Kate Lee Vertrees. They married and created Judge Vertrees Walton, my great grandfather.

Vague historical hints about John William Walton became treasured family mythology over time. Here is how my aunt Kate Walton, J.V. Walton’s daughter, wrote it out once:

John William Walton’s brother was a dealer in cotton who ran the blockade in a sloop during the war. JWW signed his bond and when his brother was finally caught, it ruined him. He signed a check for $7,500 to make the bond good for him on the little slave built desk in my bed room. This pretty well cleaned him out.

JWW was not a believer in slavery although he owned slaves. When he could teach them a trade that would enable them to earn a living, he would free them. This was done for the slave carpenter who built the little desk.

I love my Aunt Katie dearly; but she’s trafficking in nonsense here. The law of Alabama and its records are quite clear:

During the slavery era, slaveholder emancipations, whether by judicial decree or legislative act, were few and inconsequential, having no real impact on the institution of slavery or the slave population. Emancipations, although once permitted by the 1819 Constitution, virtually ceased by 1831 and were prohibited by act of the Alabama General Assembly in 1859, demonstrating the unyielding nature of slavery. Emancipations did not significantly moderate an institution which was lifetime and hereditary, and the legal system provided little recourse for slaves.

I’ve seen no evidence – nor any real suggestion – that John William Walton emancipated anyone he owned. No such anecdote shows up among Daniel Reese Farnell’s examination of emancipations in his excellent paper: “Alabama Courts and the Administration of Slavery, 1820-1860.”

It’s possible, but unlikely, that John William Walton trained and emancipated a slave or two before it became officially illegal to do so in 1859. It’s more likely he trained slaves, treated them decently, and perhaps allowed them to hire out their own labor.

But let’s be very very clear: there is no chance that John William Walton would have survived – legally, financially, or physically – if freeing his slaves when they could earn a living was actually a standing personal or business policy at scale. No chance.

If he tried to surrender much of his wealth and free my family’s 400 slaves before the war, the power of the state, acting with the force of law, would have violently stopped him. And most likely, his freedom-loving American neighbors would have killed everyone associated with him, slave and master alike. That’s the kind of legal and social system slavery demanded to maintain it as an economic system.

So I suspect John William Walton enjoyed his incredibly valuable inheritance as honorably as its nature allowed; and the vaguely known evidence suggests he did better than some, if not most.

Also, $7,500 did not “pretty well clean out” a family that owned 400 slaves, even through the dislocation of the Civil War and relocation from Alabama. Capital persisted across generations and found its way into the family land and homesteads I grew up enjoying in Palatka, Florida.

My family bought, inherited, and lived on our land legally and ethically, according to the laws of the United States of America and the state of Florida. But we did so with the enduring help of expropriated property; stolen labor; and plundered generational wealth — which was also expropriated, stolen, and plundered legally and ethically.

That’s the Walton story.

Jacob Vertrees’ all-powerful penis

The Vertrees family part starts with Jacob Vertrees, J.V. Walton’s great grandfather on the Vertrees side.

Like many masters, Jacob Vertrees chose to insert his gentleman’s penis and ejaculate into at least one property to which he or a relative held title. It is unclear if this property consented to the insertion of this master’s penis – or if property can grant sexual consent in any meaningful sense. Jacob impregnated that property, whose human name escapes any record I could find. This nameless female property gave birth to a boy named Booker Harding.

Booker Harding entered a relationship with a white woman named Polly Skaggs. I don’t know the circumstances of how that happened; but Polly Skaggs was said to be descended from Patrick Henry, of “Give Liberty or Give Me Death” fame. Unlike his father, it seems likely that Booker Harding received Polly Skaggs’ consent to human-to-human sex. As a result, she bore a son named Peter in 1840.

The pre-Civil War Kentucky courts required that Polly Skaggs surrender the miscegenated child she birthed before his 5th birthday. So she made a deal, turning the child over to the custody of his grandfather: Jacob Vertrees.

That’s right, only the very slaveowner – my great great great great grandfather – whose all-powerful penis and ejaculation created the family and legal crisis could resolve that crisis by assuming sovereignty over his grandson and ripping him away from mother and father.

In 1935, Marjorie Rawlings wrote this to her agent and friend Max Perkins:

I’d hate to estimate how many white men have had relations with negresses. Where do people think our rapidly increasing numbers of mulattoes have come from? The negro race is being absorbed so rapidly that a hundred years from now people will wonder why on earth there was talk, in our day, of the race problem in America.

“Relations” is another curious euphemism; and more than 85 years later, “talk of the race problem in America” persists, to say the least.

But Marjorie quite effectively punctures the tonal mythology of Kate Walton’s wishful thinking here. The temptations and prerogatives of total sovereignty and power over another human being – right down to the most intimate pleasure centers of the body – proved irresistible for legions of white men throughout American history.

As a child and young woman, Kate Walton’s grandmother and namesake – Kate Vertrees Walton – lived in household familiarity Peter Vertrees. She lived in constant awareness of the fruit of the master’s incentives and prerogatives and appetites.

That part seems never to have been communicated to my aunt Kate Walton in a way that she would write down as exculpatory myth.

“The date I have never known, the place I cannot remember and my father I never saw.”

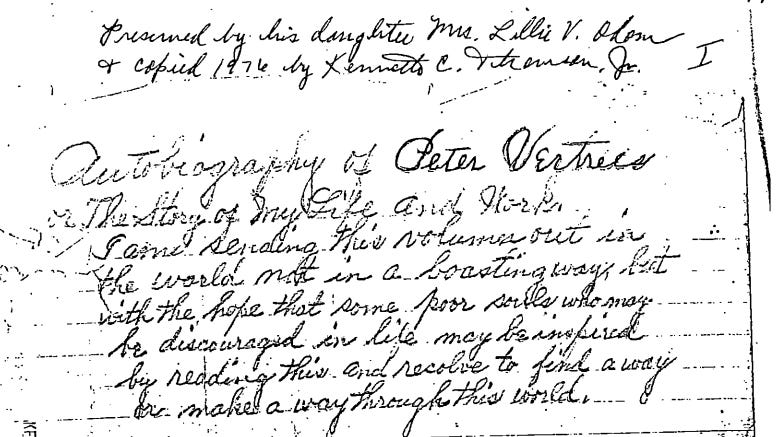

My distant black cousin Peter Vertrees wrote a terse and beautiful autobiography during his “declining years,” likely in the 1920s.

Today it resides with Western Kentucky University. Peter wrote it by hand, in immaculate script, on ruled paper, with scratch outs and edits and parentheticals and other imperfections of production. It appears that Peter, or family, underlined key passages and inserted little notes here and there. This intimacy of the script and edits only deepen the power of the narrative that flows through Peter’s disciplined and skilled written voice.

Here’s how it opens, with brackets indicating an inserted annotation:

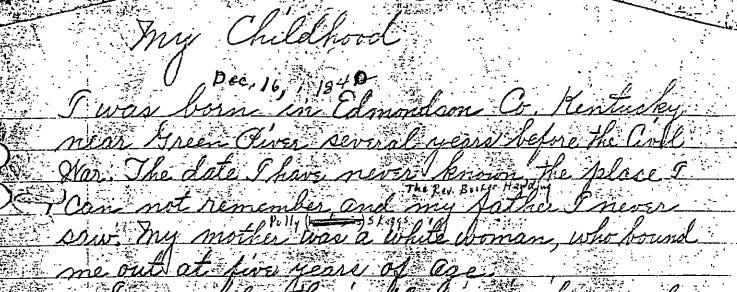

I was born in Edmonson Co. Kentucky near the Green River several years before the Civil War. The date I have never known, the place I cannot remember and my father [Booker Harding] I never saw. My mother [Polly Skaggs] was a white woman who bound me out at five years of age.

I remember the incident as if it was only yesterday. My mother got on a gray horse and put me on behind her and rode several miles through thick woods until she came to the home of Mr. Jacob and Mrs. Kitty Vertrees. We went in and Mother made her arrangements for me to stay though I did not know this until afterwards. Mother took me in her lap and I fell asleep; when I awoke Mother was gone, and I have never seen her from that day to this.

I cried so bitterly for mother. Mrs. Vertrees, whom I learned to call mother did everything she could to quiet me and make me satisfied. She gave me sugared biscuits and many other dainties relishing to child appetite.

Gradually I forgot to cry for my real mother and learned to love most dearly my fostered mother; for she was indeed the best woman I knew.

Peter was given the Vertrees name and raised in the Vertrees household in something very close to full family status.

Absolutely nothing Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings ever wrote matches the emotional power of the bond Peter describes sharing with Kitty Vertrees, who must have known she was caring for the miscegenated outcome of her husband’s sexual dominion over property.

From across generations, I wonder if Kitty – my great great great great grandmother – understood Jacob as unfaithful to her. Or did reproductive acts of sexual power with property fall into some other category of betrayal or acceptance? Did she perceive her husband as a philanderer? A rapist? Or just a man. Was intercourse with property a misdemeanor sexual sin best ignored, perhaps akin to masturbation?

I don’t know how to answer any of those questions.

It probably depends on how Kitty perceived the humanity of the property whose womb birthed Booker Harding – the man whose penis lacked the dominion to empower Polly Skaggs as Peter’s mother.

I don’t have Kitty’s words to tell me.

But I do know Peter’s account of how Kitty chose to love the living consequence of her husband’s behavior. I suspect it says much about her perceptions of humanity:

Day by day I became more pleased with my surroundings. Everybody was kind to me and seemed to be interested in me, and naturally I became interested in myself. Mother, as I called her, took all the pains in the world with me. Many cold winter nights has she gotten up from her bed and come to mine and felt of my feet and would tuck the cover about me so snugly until it was almost a matter of impossibility for me to get cold.

Kitty also animated Peter’s yearning to minister.

Mrs. Vertrees was a very devout Christian. She had her prayers three times a day regularly. She taught me to pray and inspired me very much by her devotion. She would make me sit down beside her and she would tell me that I was motherless and fatherless, but if I would love Jesus and be a good boy he would take care of me. She attended church…I would sit by her side during service and listen to the preacher. I said in my heart, “I’ll do that some day.” I would go home and take the trees, stumps, weeds, and flowers for my congregation. And I would preach to them and cry like a baby. My daily Christian training was kept up and day by day my little heart yearned for the true way and the noble things in life.

I’m reminded in this passage of John Lewis ministering to and baptizing chickens as a boy.

Jacob Vertrees also inserted his penis and ejaculated into Kitty often enough to help breed 11 more legally tidy white children, whose DNA was not a crime requiring erasure of the parents who created it.

The white Vertrees children – who would actually have been Peter’s uncles and aunts – appear to have welcomed their mixed race miscegenated half-brother/nephew.

In the Vertrees home, I spent many happy hours. The children were very nice and kind to me. They were all near about grown when I was bound to their parents. They did not mistreat me and did not allow anyone else to do so.

It’s unclear from his autobiography if either Peter or the “legitimate” Vertrees children knew they were related by blood. Peter never speaks of Jacob as his grandfather. And he never even clearly describes himself as belonging to any race, which, of course, he didn’t biologically. Instead, he occasionally identifies “white” or “colored” people as characters in telling his story; and his interactions with them suggest whether or not he is one of them.

Socially, Peter gradually became blacker and blacker over time though circumstance and choice – with perhaps the clearest declaration coming in an account of a Ku Klux Klan threat to his church.

This happened long after he left his second of Vertrees homes on friendly terms soon after the Civil War, as a free black man fully supportive of both his own enfranchisement and the Radical Republican aims of Reconstruction.

James Cunningham Vertrees: lawyer, judge, newsman, traitor

That second, post-Civil War Vertrees home belonged to Judge James Cunningham Vertrees, one of Jacob and Kitty’s 11 children. He was grandfather to Judge Vertrees (J.V) Walton, who was named for James Vertrees’ status as a judge. That makes Judge James Vertrees my great great great grandfather.

James Vertrees married Susan Catherine Lee in 1849. My family stories have always included a vague notion that we’re related to General Robert E. Lee, the most exalted of all self-consciously white southerners. I’ve never been able to pinpoint how; but if the connection exists, it almost certainly comes through Susan Lee Vertrees. She gave birth in 1853 to Kate Lee Vertrees, J.V. Walton’s mother, in Tennessee.

Shortly afterward, James Cunningham Vertrees and his family pioneered to the border of the Missouri and Kansas territories, just outside Kansas City. There, in 1855, James founded the “The Richfield Monitor” newspaper in Missouri City, which, today, is a decaying hamlet on the banks of the Missouri River.

The newspaperman later became judge of the Probate Court of Clay County, of which Liberty, Missouri, is the lovely county seat, located a few miles from Missouri City.

Judge James Vertrees was almost certainly a supporter of the pro-slavery side during the popular sovereignty, John Brown, “Bleeding Kansas” border war days that helped spark the Civil War. But I don’t know if he took active part in cross border raids or violence or election-rigging.

When the Civil War came in 1861, James joined up with as a lieutenant in a Confederate-aligned state militia infantry company. It appears that he took part in the Battle of Lexington, in which 12,000 Confederate-aligned state soldiers, led by General Sterling Price, laid siege to the town of Lexington in September of 1861 and forced the surrender of 3,500 Union troops stationed there.

The Union quickly struck back, retaking and holding most of Missouri for the duration of the war. This had consequences for James Cunningham Vertrees, as explained in a history of Clay County, Missouri:

Our citizens were greatly surprised on one Sunday early in December, 1861, to find a large body of soldiers under the command of Gen. B. M. Prentiss, of the regular United States army come into Liberty, where they remained until the Tuesday following. During their stay numbers of persons of Confederate proclivities were arrested and forced to take the oath of loyalty to the Federal government. When this general departed with his troops, returning to Leavenworth, he carried with him Judge James C. Vertrees, judge of the Probate Court, J. J . Moore, deputy sheriff, James H. Ford, constable, and about a dozen other prominent citizens.

And that’s where I lose track of James Vertrees, my great great great grandfather, until he plays a major role in the notable life of his blackening nephew Peter Vertrees after the Civil War.

Gallatin

I’ve known the surname Vertrees since boyhood, through family osmosis. But specific first names attached to it came much later, as I researched Age of Barbarity, my first book.

And Peter Vertrees, arguably the most famous Vertrees, entered my consciousness only very recently and by accident – on a fall 2019 side trip to Gallatin during a long-weekend of music and partying with my wife and visiting friends in Nashville and Chattanooga.

I was looking for the gravesite of John William Walton, who I knew was buried in Gallatin. Here’s his grave monument. It’s what you might expect from a wealthy slave-owner/industrialist.

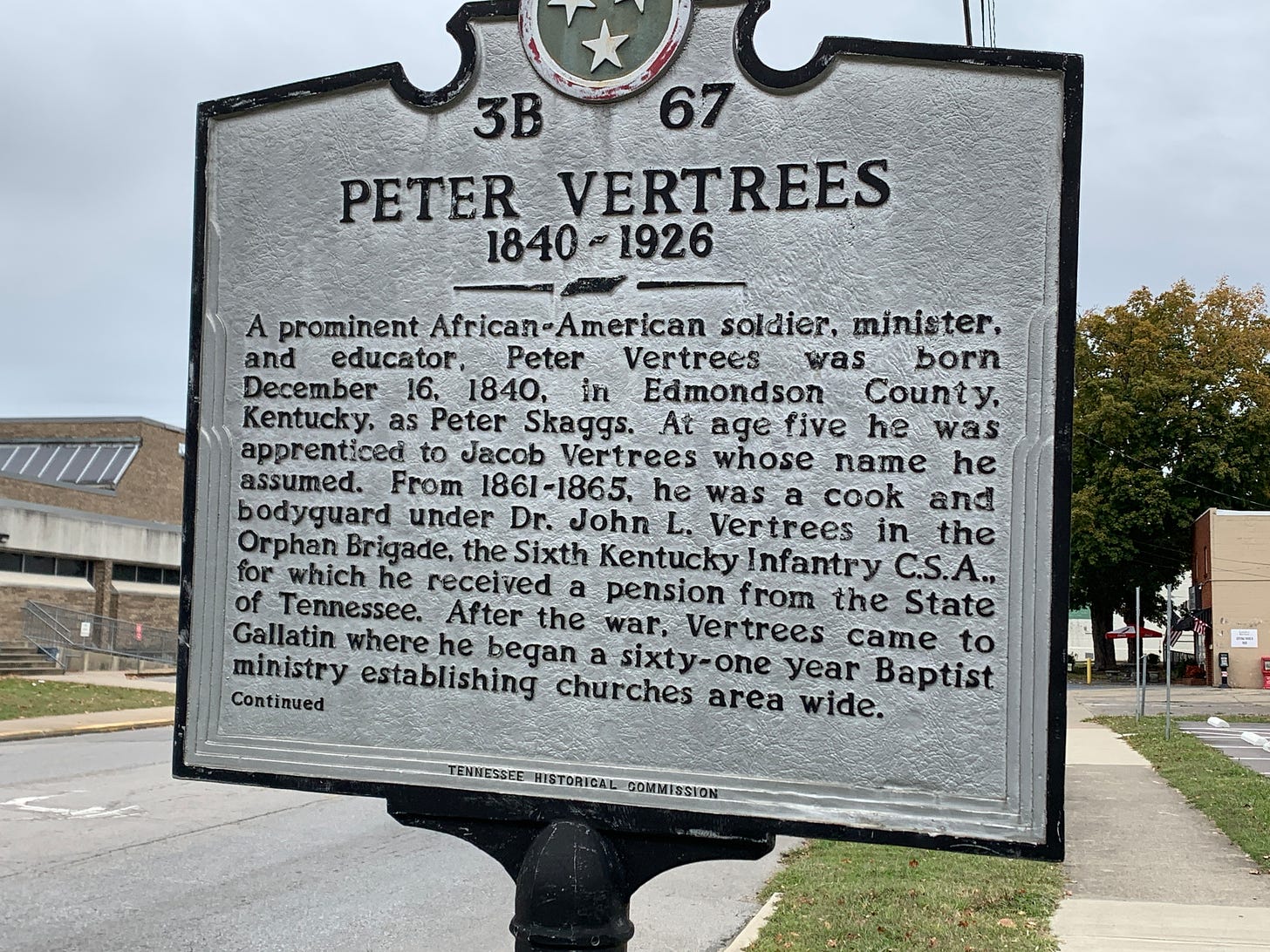

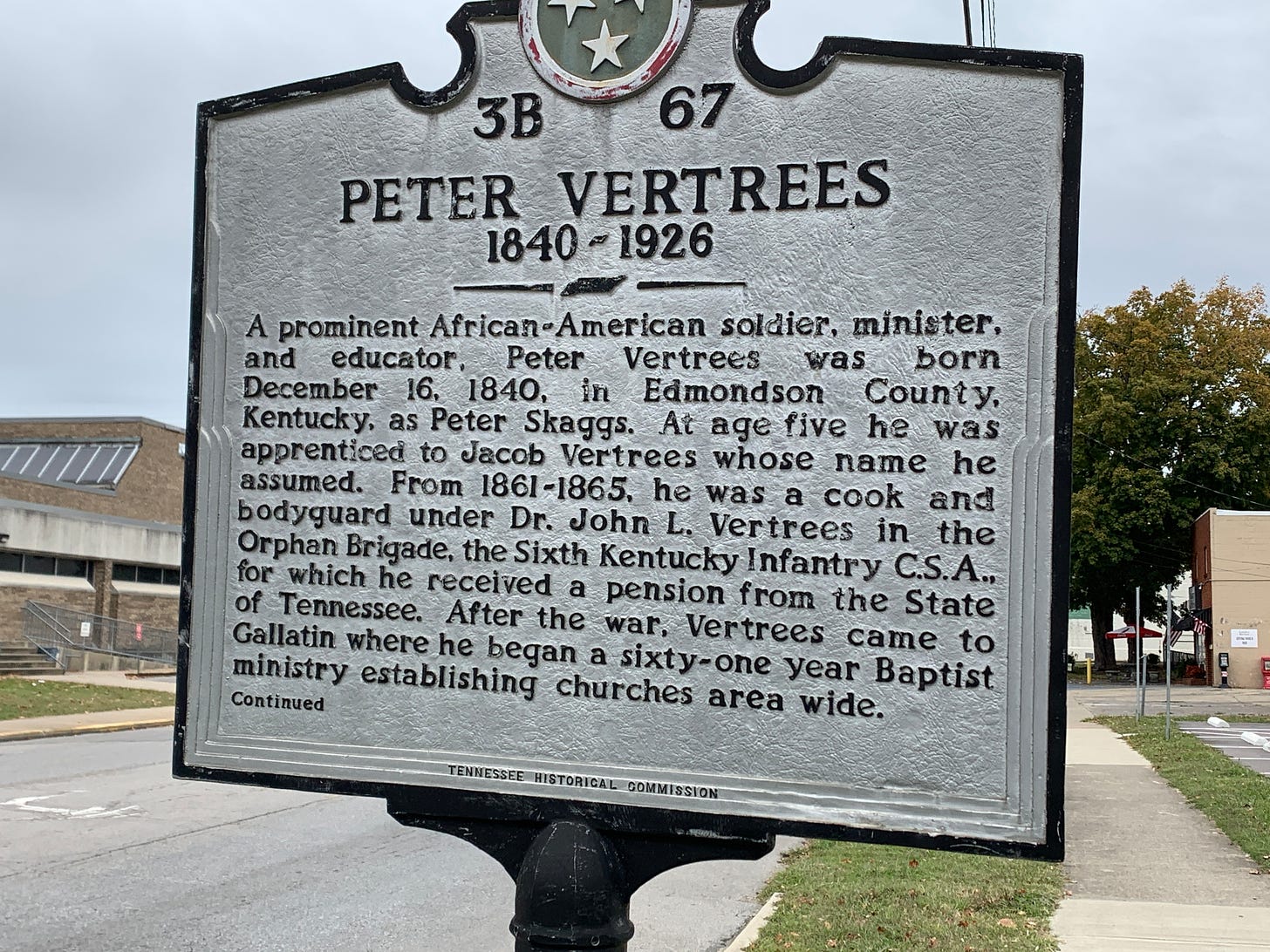

As we entered the town, I noticed a historical marker with “Vertrees” at the top. It reads like this:

A prominent African-American soldier, minister, and educator, Peter Vertrees was born December 16, 1840, in Edmondson County, Kentucky, as Peter Skaggs. At age five he was apprenticed to Jacob Vertrees whose name he assumed. From 1861-1865 he was a cook and bodyguard under Dr. John L. Vertrees in the Orphan Brigade, the Sixth Kentucky Infantry C.S.A., for which he received a pension from the State of Tennessee. After the war, Vertrees came to Gallatin where he began a sixty-one year Baptist ministry establishing churches area wide.

Dr. John Vertrees and James Vertrees were brothers, the biological children of Jacob and Kitty. That made them Peter’s biological uncles; but he experienced them like older half-brothers.

“I never was a soldier on the firing line.”

The Sixth Kentucky Infantry was often attached to the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Gen. John Breckenridge nicknamed it the Orphan Brigade because the U.S. Army had seized control of Kentucky, which never seceded from the Union anyway. The Confederate “orphans” could not go home.

The Orphan Brigade took part in basically every major battle of the western river theater, from Shiloh to Vicksburg to Chickamauga to the Chattanooga breakout at Missionary Ridge. Of that momentous macro military history, Peter wrote only this:

These days of bitter conflict made lasting impressions on my mind. Never can I forget Shiloh and Vicksburg.

As the marker and my subsequent research shows, Confederate nostalgists seem to have embraced the “Black Confederate” vibe that a surface look at Peter’s life gives off. And I suspect his Tennessee Confederate pension – rather than his works as a minister – gave marker makers their incentive to memorialize him.

The marker makers certainly did not memorialize Jacob Vertrees’ penis – only the unspoken grandfather’s benevolent offer of apprenticeship to young Peter. “Apprenticed” is an intriguing way to describe a grandparent’s relationship to his illegal grandchild.

Whatever the motives of the marker makers, to call Peter a “soldier” or “apprentice” is to vastly distort the meaning of those words.

Peter himself said, explicitly: “I never was a soldier on the firing line.” The only “combat” he described came near Vicksburg, when an ill-advised horseback ride to the Mississippi River to catch fish exposed Peter to a federal gunboat, which opened fire on him and missed. It’s hard to know what he saw at Shiloh or Chickamauga or Vicksburg that he could never forget because he did not describe it.

What he did describe, in extraordinary and emotional detail, is how his war experience became a personal spiritual quickening. Moreover, it becomes a historically significant firsthand account of a wider and well-documented Christian “awakening” within the demoralized Army of Tennessee after the disastrous defeat at Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge. “Emerging evangelist” best defines the role Peter saw for himself and described during the Civil War.

Indeed, the most personally traumatic and momentous event Peter describes during the entire war years isn’t battle or deprivation. It’s the far away death of Kitty Vertrees, the only woman he could call mother, and what it led him to:

These days of conflict made a very great change in me at first but proved helpful to me in the end. I learned to attend balls and drink and curse and gamble. This was decidedly against my training. About the second year after we left home the sad news came that Mrs. Vertrees was dead. I wept sorely for the [illegible] that my best earthly friend had gone from me. I remember some time after hearing of her death I was at a big ball away down in Georgia. I was on the floor trying to dance (never could dance, for I was too tall and awkward) when seemingly I heard Mrs. Vertrees call me. I left the floor and ran out of the room into the darkness of the night and wept as Peter did when he denied his Lord. I never attempted to dance again. The passing away of my best earthly friend caused me to seek that Friend of friends – Jesus Christ.

My first attempt was made at an outdoor service for white people. The minister called for those persons who wanted to know Jesus Christ to come forward. I went forward and knelt by a stump. When service closed the people went on away and thought nothing about me. This caused me to decide to never give up until I found the blessed Christ – the friend of sinners.

The next year 1863 I professed a life in Christ. I was all alone when God’s spirit was manifested in my heart. I was so happy that I ran to the trees and hugged them as a fond child would hug its mother. I was so filled with the Holy Ghost until my whole being seemed unnatural. I loved everybody and sympathized with every living thing so much that I would not kill the insects that crawled on the ground. I was baptized by the Chaplain in our company. Very soon I was [illegible] to become a preacher.

The reference to “white people” as his first audience is also the first racially aware reference Peter makes in his autobiography about anyone, including himself.

Above all, for Peter Vertrees, the war life provided a profound muse for religious experience and expression, triggered by the death of his beloved Kitty. He seems to have made himself into an informal chaplain, preaching and revivaling with soldiers and civilians alike, regardless of race, as an authority of the gospel and the emotions coursing out of it.

And we’re going to leave it there for part 1. Peter’s greatest war wound was Kitty. But his experience, in both the war and Reconstruction, anticipated so much of what we experience as a country today. Part 2 will lay that out and show how relevant Peter Vertrees, this most uniquely American of Americans, remains today.

Thanks for sharing.