Sundays with "A Man or a Mother:" The spider, the daughter, the maid, and the husband

This week's chapter looks at the multi-racial found family Marjorie Rawlings spun into her life, almost like prey, as Pearl Harbor and the Cross Creek lawsuit approached.

I’m serializing a section from my book-in-progress — A Man or a Mother: Kate Walton, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and the fight for self-sovereignty in American Florida, one chapter at a time, on Sundays. The section is called “Self-sovereignty and invasion (1933-1942).” This is the third Sunday. Here are the two chapters I’ve published so far and a trailer of sorts for the book as a whole. (All of this is copyrighted, by the way; or so I declare.)

Trailer: Introducing A Man or a Mother

Today’s chapter looks at how Marjorie became Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Baskin — and absorbed two very different and very similar young woman into her life, at roughly the same time.

Zelma Cason had been sisterless Marjorie’s first sister of found family when she moved to Florida as a little known newspaper writer of poems for “housewives” in 1928. By 1940, Marjorie was one of the most famous people in Florida. She had long cast Zelma and others aside; and she was lonely in her fame. She set about creating a new found family, just in time for war on two fronts to disrupt it.

Warning: I quote Marjorie using some ugly racial slurs in this chapter. It’s a major part of her character, as is her general, but soft, sympathy for civil rights and reputation as a racial liberal in her time and home. Today, Marjorie’s language makes a few places in this article NSFW.

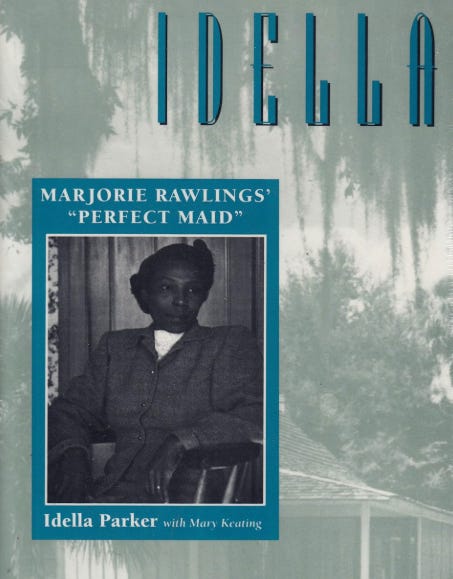

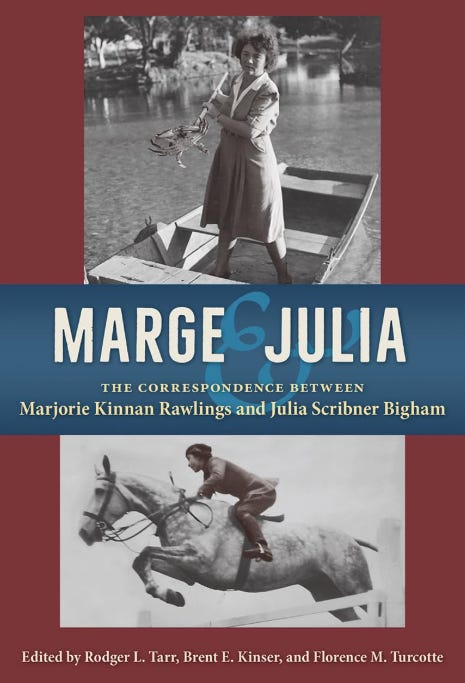

This chapter draws heavily from Marge and Julia (edited by my buddy Flo Turcotte, Rodger Tarr, and Brent Kinser) and Idella, the self-titled autobiography of Idella Parker Thompson.

Julia Scribner was an unmarried 21-year-old white heiress from New York; and Idella Thompson was a 26-year-old unmarried black maid from tiny Reddick, Florida. They both began to experience Marjorie Rawlings and Cross Creek intimately in 1940.

Other than sex and age and marital status, they were abstract opposites in the reductive American status imagination.

But when you forget that; when you screen out the immutable sense of social and racial essence hardwired into Marjorie’s processing of them; when Marjorie just relates what she likes and admires about them as young women in her company, the commonalities of Idella Thompson Parker and Julia Scribner explode off whatever type of page holds their descriptions.

So do the diametrically opposite and similarly claustrophobic prisons of a talented young American woman’s existence – from which Marjorie offered both of them a very conditional measure of parole.

Here is Marjorie writing to Julia, the daughter of her publisher, Charles Scribner, in 1940 and then in 1943:

We have so many tastes in common that I think you would like my quiet life—and there are some awfully nice day-trips we could make—Bok Tower, Silver Springs, and any other places that may appeal to you.

***

How I wish you were my daughter! You are exactly what I should choose if I could have a daughter, and I would be the right sort of mother for one like you.

And here is how Marjorie described Idella in 1942, in the “Black Shadows” chapter of Cross Creek:

There came to me, in answer to prayer, a reward for my sufferings, the perfect maid. She is well trained, as good a cook as I, well educated, with almost my own tastes in literature and movies. She loves the country, she loves my dog, she dislikes liquor, and has no interest in men. The Lord taketh away but the Lord also definitely giveth. Blessed be the name of the Lord.

I find it very difficult to discern what Marjorie considered the difference between a perfect maid and perfect daughter, other than race. Julia and Idella could be sisters.

And yet, of course, they couldn’t.

In the last chapter, I quoted Marjorie warning Max Perkins of “the jealous, female-spider-like possessiveness of the inferior female who tries to absorb a superior male—and, nine times out of ten, succeeds.”

Marjorie, never lacking for projection, spun Julia and Idella into her life, almost like prey, at about the same time.

At age 43, she wanted the perfect daughter and perfect maid. Julia and Idella offered her both, for many of the same reasons. And they would both love and sour on their spider, for many of the same reasons. Some were emotionally complex, and some, quite visceral and immediate. For instance, Marjorie almost killed both Julia and Idella in different drunk driving accidents without a hint of remorse.

The surrogate daughter and “perfect maid” met and knew each other.

But the only record I know of their interactions comes from Idella’s deeply compelling, self-titled late-life autobiography published in 1992.

Idella recounted the first time she met Julia, when Marjorie, who was ill, sent Idella to pick up Julia for one of her visits from the train station in Gainesville. She gave her a casually humiliating order to call out for “Miss Julia” randomly when the train arrived. Idella writes:

Finally a sophisticated young woman with close-cropped blonde hair got off the train, and said, “I’m Julia,” and I was saved from further embarrassment. She wore a double-breasted tweed pants suit, and she looked like a college student, so young…

… Many years later, recalling this incident, I thought to myself, now why didn’t we make a sign with Miss Julia’s name on it, and I could have held it up, and not had to yell like that? But at the time it never occurred to me to question anything I was told to do. That’s just how things were.

Julia Scribner came to visit many times after that, and she was a very nice young lady. I was always pleased when Mrs. Rawlings would tell me that we were going to have a visit from Miss Julia.

How I wish we had correspondence between Julia and Idella that might explain Idella’s purposefully-expressed affection for her fellow 20-something attached to the great woman.

When Marjorie got hammered and passed out – not unusual – did Idella and Julia sit on her porch in the dark and share their lives with each other? As friends? As equals? Both seem curious and internally open and yet socially cloistered enough to identify each other as kindred spirits trapped in different worlds. That could have happened.

What would these two “nice young ladies” say to each other in confidence?

I entertained the idea of fictionalizing a conversation between them; but it would just be what I want to happen, untethered to any hint of evidence beyond my wishful inference.

I’m stuck instead with grumpy Marjorie, struggling to structure early drafts of Cross Creek, describing Idella to Julia in a November 1940 letter, when the mother-daughter and “perfect maid” vibes were still very new.

The only bright spot is my new darky maid, who is too good to be true. Think the Lord is holding her like a carrot in front of my nose, to lure me into a sense of comfort and security, and plans to snatch her away just as I settle down in peace…

…Idella, the new nigger, has a sister at the colored normal school in St. Augustine, and I had her down to keep Idella company. She thanked me for a pleasant week-end and said fervently, “Anything to get away from the campus.” Idella has been reading my books and is enthusiastic. Don’t know whether to salve my pride by believing she’s just diplomatic, or whether to accept the fact that I have found the group audience I write for.

***

You get a sense of coverture in how Marjorie brought both young women to Cross Creek – of mobilizing benevolent, yet vaguely sinister authority beyond the capacity of their agency to question.

Julia came first.

She and Marjorie met in December 1939 at the Scribner estate in New York, during a celebratory post-The Yearling visit. They seemed to connect immediately – the childless 43-year Pulitzer Prize winning author and the sensitive, lonely, 21-year-old sophisticate aesthete beginning to question the values inherent in her parents’ wealth. (Again, the Trio mother-daughter vibe is unmistakable.)

This is from Marjorie’s second letter ever to Julia, from February 1940, a couple months after she met Julia for the first time at the Scribner’s “Dew Hollow” estate in New York. Note the bold.

Dear Julia:

I sounded out your father on the idea of your driving down with them when they go to Palm Beach and spending a week with me. I was delighted when he wrote that he was sure you would like to come. So I’m writing you direct—and hope nothing will happen to prevent your coming.

Thus, after one family hangout, and two letters, Julia came to spend two weeks at Cross Creek with Marjorie while her parents toured other parts of Florida.

Upon leaving, she wrote this on a train in what appears to be the first letter she ever sent to Marjorie, who she called “Mrs. Rawlings.”

There is a great deal I would like to say here, but I only seem able to curse and “blunder around” in my head and not a single coherent sentence leaks down from my brain to my hand. I am so very grateful and gratitude seems a particularly difficult thing to express.

Oh Hell with my inarticulateness …

… I would like to tell you in poised but glowing prose how very happy I was with you, (and I don’t mean just “having a good time”), how much I miss you and how lonely I am when I think of something I would like to talk to you about or see something I think you would enjoy, and most of all, how proud I am of your friendship.

They were quickly filling some very deep mutual need.

Now here is Idella, in her autobiography, describing her first meeting with Marjorie. in the summer or fall of 1940. That’s when Marjorie essentially stole her away from another potential employer through a quirk of the local domestic worker grapevine.

[Marjorie] began talking very fast, the way I soon learned she spoke when she intended to get what she wanted.

“They tell me you’re looking for work as a cook?”

I replied quickly, “Oh yes, ma’am.”

“That’s good. Can you cook?”

“Oh yes, ma’am, I’m a good cook.” I was nodding enthusiastically now. By this time she had her checkbook out and was beginning to write quickly as she talked, asking me to spell my name.

As she wrote, she rattled on, fast as you please, “Now I have to go up to New York and Maryland for a few weeks, but this check will bind us. Do you know where Island Grove is? Cross Creek is about five miles outside Island Grove.”

By this time she had the check all made out, and she handed it to me. I looked at it a gave it a start, because I saw the name on the check was not Camp at all, it was Rawlings.

“Oh no, ma’am,” I said in a loud voice, “I’m to work for Mrs. Camp. She lives in Ocala, not Island Grove.” I tried to hand the check back to her, but she just waved it away.

I continued my protest, “But I’m to work in Ocala for Mrs. Camp.”

Mrs. Rawlings looked up with a mischievous smile in her blue-gray eyes and said, “Oh no, Idella, you don’t want to work for Mrs. Camp. She’s hard to get along with.”

***

The richness of Idella Thompson Parker’s American Florida story before she came to Cross Creek would have made a great book if Marjorie could have ever conceived of a black woman – even a “perfect maid” – serving as the lead character in her own story. She absolutely could not. No black character in any of Marjorie’s work demonstrates agency or an imaginative inner life.

She would never have considered building a novel around a black protagonist.

And that’s probably for the best – when we consider the characterizations and tropes of the “Black Shadows” chapter in Cross Creek.

Indeed, Marjorie should have been proud that Idella claimed to like her books.

I consider Idella a far more valuable book about Florida than Cross Creek. Better is a more complex question; but Idella fills the giant racial agency hole in Marjorie’s “interpretation” of Florida life – backwoods cracker and otherwise – with efficient, honest, and magnanimous memoir.

It’s infinitely more human and honest, not hung up on its self-conscious “interpretation.” It manages to achieve that authenticity without resorting to cheap tricks like phonetic mutilation of speech. The autobiographical narrator of Idella is far more comfortable with herself than the narrator of Cross Creek or Blood of my Blood. And Idella is more revelatory and moving than both because if it.

Idella makes clear that “21-year-old white heiress” summarized Julia Scribner’s resume of life in 1940 far more completely than “26-year-old black maid” did for the quite well- educated Idella Thompson’s.

I’m going to risk a few additional brief excerpts from Idella to underscore this education:

Although she was good at many things, Mama had little formal schooling, yet she taught all her children that education was all-important education was all-important. Because she made us so firm in that belief, all her children strove to get a good education and better themselves.

My sisters Thelma and Eliza became schoolteachers, Dorothy became a nurse, and Hettie was a teacher of nursing. My only brother, Edward Milton, called “E.M.,” was studying to be a mortician before he was called into World War II and killed in action.

To send a black child to school in those days cost money. Not much money, but often more than we had. One year, in order to pay the school fees, Mama pawned the only thing her own mother left her, a gold piece. She got two dollars for it, enough to pay for school.

She had several months to pay the local pawnbroker back and reclaim the gold piece, but somehow she just never had enough money to do it. When she was finally able to scrap the two dollars together, the pawnbroker refused to take the money and wouldn’t give the gold piece back.

I came home that day to find Mama standing at a window, staring out and crying. Mama was a big, strong woman who seldom cried, and it broke my heart to see her weeping so. She didn’t want to tell me what was wrong, but I got the story of the gold piece out of her bit by bit. That’s when I made up my mind to go to work and help out, so Mama would never have to cry like that again. I got me a job within a week, washing dishes at Miss Alice Dupree’s boardinghouse in Reddick. I was thirteen.

While working, Idella walked to school for the three months per year it was open for black children. She excelled – and found herself briefly under the tutelage of Mary McLeod Bethune as teenager.

I finished eighth grade at our local school, which was called Mount Zion, and I attended Fessenden Academy in Martin for one year afterward. I was an A student, excelled at basketball and baseball, and I was often the teacher’s helper. The following year, 1929, I was sent off to Daytona Beach to attend Bethune-Cookman, which was a high school in those days. Mrs. Mary McLeod Bethune, a remarkable lady who knew every child by name, ran the school with a rod of iron, tempered with love and understanding. I did well there, but I was sickly, and after a few months I had to be sent home.

I was quick at my lessons, and I loved to read. At home I made my three younger sisters and my brother play school, a game in which I was always the teacher. I began to think that I would like to teach young children, so I went up to Gainesville in 1929 and took the teacher’s exam. There were three grades of certification, and I came away with a beginning teacher, or “third grade,” certificate. I was sixteen.

The reality of teaching in a tightly supervised, Jim Crow system did not meet Idella’s romanticized notions – an experience with which so many teachers of so many eras, including our own, can relate.

To tell the truth, the work was not what I thought it would be. We were watched carefully by supervisors like Peter Brown who rode from school to school on horseback. It seemed to me they meddled a lot more than they needed to, not only in children’s learning, but in the teachers’ personal lives. They even went so far as to tell teachers where they could go after school hours, and where not. I decided teaching was not for me and did not return to it until many years later.

Having left teaching, Idella turned to domestic work – which was about all that was available to a black woman in 1933.

In those days if there was no work, you had to go find some or starve. It was common for black people to travel up and down Florida to find work. Some followed the crops, picking as the crops ripened. Others worked for rich white folks at the fancy seaside resorts.

Papa went to the resorts to work for several years. He would travel south to Fort Myers or Palmetto and work as a busboy during the winter season, then come back to Reddick to build boxes and sharecrop when the resort season was over.

Idella convinced her mother to let her travel to West Palm Beach, where she found a measure of independence and happiness – first working in a boarding house and then with living with “a nice white family” for five years.

I loved West Palm Beach, loved being independent, and I had a fine room in a grand house to live in. I had many friends and an active church life there. It was a good life.

A shitty man wrecked the good life for her – and sent her home.

He was handsome and fun, and she seemed wonderful at first, but in time Joe’s attentions became abusive, and his presence in my life was disturbing. He began turning up at the Bowens’ home and making scenes, so bad that after a while it was clear that the only way to get away from him was to leave West Palm Beach. Reluctantly, I left the Bowens and went home to Mama.

Remember, Idella “has no interest in men,” if one believes the narrator of Cross Creek.

That’s quite an “interpretation,” as Marjorie would say.

You might also call it another blithely false, intensely lazy public description of the sexual behavior or identity of a woman with whom she supposedly shared intimate affection –published for the purpose of paid entertainment.

Idella’s “interest in men” is the entire reason the supposedly sexless “perfect maid” had to leave her beloved oasis of West Palm Beach to slum it with the country sophisticate.

Amusingly, when it came to Idella, Marjorie eventually copped to her “ignorance” – in maybe the most insulting and possible way.

Well, my God, I just don't know nothin’ about nobody. Of course, why I should ever expect even the most demure negro woman of 28 to be a virgin, I don't know. Anyway, I thought Idella was. A few days ago, she told me she had been married in West Palm Beach, and one reason she came up here was because she wanted to get entirely away from him. I asked what was the matter with him, and she said, “a little of everything.”

Do you ever feel overcome with ignorance? At the moment, I don't know what anything is about. I should set up in business to write about human nature! Yeah me and who else. Anyway, I can write just to spite other ignorant people.

Idella explains the pain – and potential danger – of this retreat from glamorous West Palm Beach versus to Marjorie’s backwoods wonderland in Marion County. Idella’s mother literally thought Idella was risking her life to accept Marjorie’s “job offer.”

“You know you can’t work in no Island Grove, child. They’ll kill you!”

I knew what Mama was talking about. I’d been hearing stories about how sometimes colored folks mysteriously disappeared in Island Grove ever since I was a child, and those scary tales came rushing into my mind. Island Grove was a white man’s town, a place where colored people were not welcome. We all feared Island Grove, that cold fear we all had of whites in those days. Mama was fearful for my safety, of what might happen to me if I so much as set foot in Island Grove. I was fearful of what might happen if I didn’t take the job after Mrs. Rawlings had paid me in advance.

***

Marjorie married Norton Baskin on Oct. 27, 1941 – within a year of absorbing Julia and then Idella into her intimate life.

By that time, if we believe what Marjorie told Julia, she had been “hot on [Norton’s] trail for eight years” – or literally since her divorce from Charles in 1933.

Yet, in 1944, Marjorie also told Julia the following, while her still new husband Norton was off serving as a combat medic in Burma in 1944:

The one man I was in love with, whose work seemed valuable to me, was married and conditions were such that I was the first to admit that he could not become unmarried, to marry me.

That man was not Norton Baskin.

Marjorie’s biographer Anne McCutchan and the editors of her letters to Julia make a convincing case that it was Major Otto Lange, a graduate of West Point, an Army commander, and ROTC instructor of the University of Florida.

Lange was married; and it seems pretty clear he and Marjorie had a rather steamy affair – born of shared enthusiasm for hunting and fishing. Lange called Marjorie “Diana,” after the Roman goddess of the hunt.

Lange’s letters circa 1935 and 1936, recounted by McCutchan, sound awfully smitten.

“What a joy and a relief these days together are to me,” Lange wrote in one note. “I hope you get as much pleasure and happiness out of them.” In another letter to Marjorie, recounting a rainy business trip from Jacksonville to Gainesville, he asked, “Did you feel me thinking of you riding through the storm on the train last night?”

And then they come to sound like basically everybody else who ever got into an intimate – sexual or otherwise – relationship with Marjorie. This is also from 1936, as documented by biographer McCutchan.

[Lange] wrote to Marjorie that she had “convinced me that I must be the mean, selfish, stuffy character you have so often charged me with being. I simply am not in your class and cannot measure up to what you require in a man, to give him your real respect and regard.” He followed this letter with another note, presumably a reply to one of hers. He had missed her, but he begged her not to write “one of your vitriolic and abusive letters; to begin with, I shall never read any letter from you again, and in spite of it I would still be very much attached to Diana.”

Again, Lange is “the one man I was in love with,” as the married-to-Norton Marjorie wrote to Julia 10 years later.

I don’t know if Lange and Norton were aware of each other as rival suitors – or if Norton even was one – in the mid ‘30s. But if Marjorie was truly hot on Norton’s trail while carrying on with a married man she actually loved, one has to admire Marjorie’s shambolic intimate energy, at least.

By 1938, she was identifying Norton to Max Perkins as her emergency contact. And shortly after, Norton and his buddies – “the three musketeers who are like brothers to me,” as Marjorie told Max – convinced her to consult with Zelma Cason’s brother about the dangerous surgery.

In 1939, at the peak of her Yearling fame and success, Marjorie wrote to Norton lamenting his unwillingness to marry her – partly because she loved him, but mostly because the individual is a lonely god, as Kate Walton might say:

So: what did I want? Frankly, marriage. You did not. You said once that you did. You said once also that you had nothing to offer me. Let me try to give you my idea of marriage. I am not concerned with the legal or social of ethical aspect of it. It is just that I am convinced that the greatest good can be had of life when a man and a woman who love each other and are happy in each other’s company, live it together.

I loathe living alone. I need more solitude, more privacy, than most women, but even I can get all I want in the course of a day. My work does not satisfy me as the end and aim of my life. It is something I have to do, but it does not fill and complete my life. Neither am I satisfied with what might be called weekend love, romantic and charming as it really is. I want the quiet satisfaction of living with a man I enjoy…

…I am torn most of the time between my real love for you, and my desire for a type of man and woman life that I think is impossible for us. If I could accept loneliness and just go ahead and enjoy you when we are together, as you enjoy such as arrangement all would be well. If I could make up my mind to break with you entirely and set out on a deliberate and somehow shameful manhunt, I would not be so tormented.

In June 1940, as Julia was rapidly becoming the daughter Marjorie never had and the Germans were overrunning the French, Marjorie and Norton were still in the will-they or won’t-they phase of courtship (which was more like systemic hooking up).

They had a big fight; and Marjorie wrote this on June 12, 1940:

The terrible things you said, that all I wanted was a man—did you say “a little man”—to dance attendance—must have come from a profound mistrust and resentment of me. It explains the wall I often feel you put up against me—the withdrawal—the lack of any desire or need to be with me as much as I like to be with you—which haven’t fitted in with the affection I know you have had for me. I have wanted something so much closer than you have wanted and have had an awful struggle to accept the fact that what meant closeness to me, meant something irksome and “regimented” to you.

I have great respect for and understanding of, a self-respecting man’s need of freedom, and have tried my very best not to let my loneliness make unreasonable demands on you. I am sorrier than I can tell you, that you have interpreted my pleasure in being with you, as only the vanity of a predatory and arrogant woman That you are both wrong and unjust doesn’t help the situation at all, for there is nothing more I can do about it.

“’A little man’ to dance attendance” sounds very much like Lange’s “I simply am not in your class and cannot measure up to what you require in a man, to give him your real respect and regard.”

Moreover, punctuating that despairing apology to boyfriend Norton with …

That you are both wrong and unjust doesn’t help the situation at all, for there is nothing more I can do about it …

… is vintage Marjorie.

And then of course, they got married less than 18 months later, in fall of 1941.

The whole thing is quite rom-com-y, up to and including what seems like a final break-up letter Marjorie wrote in September 1941:

I have no intention of making any mystery of what I am feeling. The street was simply no place to have it out. And I don’t think it can be had out in any case.

You gave me a first class shock when you turned on me after my sputtering and said that you hated people who had fits. Your face was appalling. You really hated me. You changed instantly from my sweet Norton to someone with whom I could not possibly be close. And since you are capable of feeling that toward me either.

I make no excuses for my “fits.” I am ashamed of them. But I exercise as much control as possible for me, and when I make a trivial fuss, as in that case, or really boil over, I simply cannot help it. My temperament is what it is, volatile and high-strung—and you may use any other adjectives you want to. My virtues—if any—come from exactly the same temperament as my faults, and each is a part of the other. I couldn’t write books, I couldn’t have a warmly emotional nature, if I were a placid pond. A man who is right for me would never be upset by any fits, and certainly would not hate me for them.

Shortly thereafter, they became engaged and eloped in essentially one motion.

***

What happened between that September 1941 break-up letter and the late October 1941 wedding?

Marjorie traveled to New York for consultation with a Dr. Dana Atchley – a sort of doctor to the stars for famous artistic women.

This seems to be the determining factor in creating Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Baskin.

Part psychoanalysis, part literal gut check (Marjorie’s intestines rarely stopped screaming at her), part visit with Julia, this trip coincided with submission to Max Perkins of the first draft of Cross Creek.

And Atchley basically instructed Marjorie to marry Norton – if Norton would do it – on any terms. Here’s how she described it Norton:

Had a long session with Dr. Atchley yesterday, and he identified the cause and source of my unreasonable rages—which I told him about—so simply that I can’t see why I couldn’t have figured it out for myself. But he said that an outside, disinterested, objective point-of-view is absolutely necessary—no one can get the perspective on his own picture for himself. The rages, as I suspected, have nothing to do with you…

… I presented my immediate problems to Dr. Atchley—principally our considering the matter of marriage, and the way I am torn at the thought of giving up the Creek way of life—wanting to be fair to you, and not wanting to worry if it would mean I went on rebelling…

… [Dr. Atchley] said laughingly, “What the hell are you waiting for?” He said I needed exactly what you are, as I described you. I didn’t go into any great detail, of course, but I had to tell him about you, as I feel at a crossroads in my life.

I gave him an outline of my life, and the things that I could identify as having disturbed me. He clarified so many things for me… and so I’m giving you the chance either to run like everything or propose to me! My heart ached a little about the telephone and cottage business—I thought what a wonderful time for you to suggest the other alternative—of your really taking me under your wing, permanently.

So you think things out from you point-of-view, decide what you really want, and we’ll figure from there.

Norton, for his part, answered that he’d been ready for marriage for a long time:

As you know, I have been ready and willing for some time but want you to be sure that it is what you want. I don’t mean that I want you to assume the responsibility for its success because I realize the necessity for adjustments and understanding … I had long ago decided that any adjustments I would have to make would be a thousand times worthwhile. Nothing would make me happier than to be married to you and I sincerely think that it will work out fine.

This seems like quite a turnabout for Norton since 1939, when Marjorie lamented his unwillingness to marry.

But I don’t think that’s right.

Rather, I think Norton understood that he and Marjorie were anchored by place more than almost any North Florida couple imaginable in 1941. Place, as we’ve discussed, defined and limited Marjorie’s work. Without it, who was she artistically? Her extended universe is even more tightly bounded than Faulkner’s Yoknapotawpa.

Faulkner – when he chose to – could leave rural Mississippi altogether and produce towering works like his 1932 World War I story “Turnabout.” And even his Mississippi work consistently transcends Mississippi. “The Bear” is about much more than Mississippi.

Marjorie never proved that she could leave Cross Creek or the Ocala National Forest to create art that stood up with South Moon Under and The Yearling.

At the same time, Norton was a hotel and restaurant manager in the St. Augustine/Crescent Beach/Marineland area of Northeast Florida. The in-person demands of his career would not allow him to move to Cross Creek and live with Marjorie; and he seems to have needed and/or enjoyed the gladhanding and socializing that came with his work.

So I think we come back to a question I asked earlier: what’s the difference between marriage and intimate friendship?

Considering “the matter of marriage” likely came down to how Norton and Marjorie both defined it. Could it be a moveable feast, as Hemingway might have said? I think Norton always thought so; it took Marjorie – I loathe living alone – much longer to come around to a marriage undefined by a shared home.

I suspect Norton told Marjorie early on that he could not give up his entire career – and probably sense of manhood – to move to Cross Creek. And he wouldn’t ask her to give up Cross Creek, as both way of life and creative inspiration.

I suspect he was always happy to get married to just codify legally what they were already doing, a friends-with-benefits weekend romance of sorts. Dr. Atchley and the New York visit seem to have convinced Marjorie that was enough

Moreover, at exactly this time, Marjorie and Norton were building a sort of neutral, shared part-time home – the Castle Warden Hotel in St. Augustine. Marjorie helped Norton buy and renovate the downtown St. Augustine landmark – better known today as the Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum.

Marjorie had ended her short-lived September break-up letter with a reference to the Castle Warden “business deal.”

Your charm is devastating, as nobody knows better than you, and I don’t know whether I am permanently immune. In any case, I want to say that regardless of our future personal relations, the hotel deal is still a business deal.

Within six weeks of that letter, they got married abruptly and unceremoniously at a courthouse in St. Augustine. Marjorie didn’t even tell Julia, with whom she had spent much time during the Dr. Atchley trip. Julia was playfully aghast.

Dearest Mrs. Baskin!

You old closed-mouthed so-and-so – you might have warned me that you were going to take the plunge at once so that I could have marshalled telegrams and wedding presents etc. I was, or am, caught absolutely with my pants down. Someone told me they had read it in the paper. I didn’t even see it myself – you know I only read drama and music news.

***

Sarojini Naidu – the Indian poet, independence leader, and first female president of the Indian National Congress – once quipped about Gandhi: “It costs a lot of money to keep this man in poverty.”

(In all her writing, Marjorie herself seems to have mentioned important world-figure Gandhi only once, in a letter: “I was somehow much amused to read in the paper that poor old Mahatmas [cq] Gandhi, along with his other ills, has hookworm.”)

Likewise, it took much urbane company and skilled servant coddling to keep Marjorie a rugged individualist interpreter of the Florida backwoods.

It took much found family.

By December 1941, Marjorie’s second – and socially upgraded – Florida family was fully in place – daughter, husband, perfect maid.

And I suspect Sunday, Dec. 7, the day Castle Warden opened to the public with a swanky cocktail reception, dawned as one of the best, most contented days of Marjorie’s life. It did not last.

War, in multiple forms, would dominate the next seven years.

I need to re-read Idella's memoir.