Sundays with self-sovereignty: “Feme soles” in the time of coverture

Today's chapter of "A Man or a Mother," the story of the Kate Walton, Zelma Cason, Marjorie Rawlings "invasion of privacy" lawsuit, contemplates Florida's "lonely goddesses" of WWII.

I’m serializing a section from my book-in-progress — A Man or a Mother: Kate Walton, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and the fight for self-sovereignty in American Florida, one chapter at a time, on Sundays.

The section is called “Self-sovereignty and invasion (1933-1942).” This is the second Sunday. You can access the first week here and again at the end of this chapter. Here is a trailer of sorts I wrote for the overall book. (All of this is copyrighted, by the way; or so I declare.)

This week’s chapter has no sex scenes. Sorry, not sorry. It is entirely SFW, — with one tiny, buried, mild curse word exception.

I do appreciate the fascinating exchange I had about last week’s randily fictional portrayal of real war zone honeymooners (which will make more sense in the context of the full book) with an accomplished — and disapproving — fellow historian/reader.

Our email chat reinforced points I’m trying to make about narration. And that exchange will find its way, anonymously, into the final book.

Today, I’m particularly eager for lawyers/legal historians to read. I’m describing some fairly complex historical legal concepts — entertainingly, I hope — and would welcome any corrections if I don’t quote nail something.

Here we go.

“Feme Soles” in the time of coverture

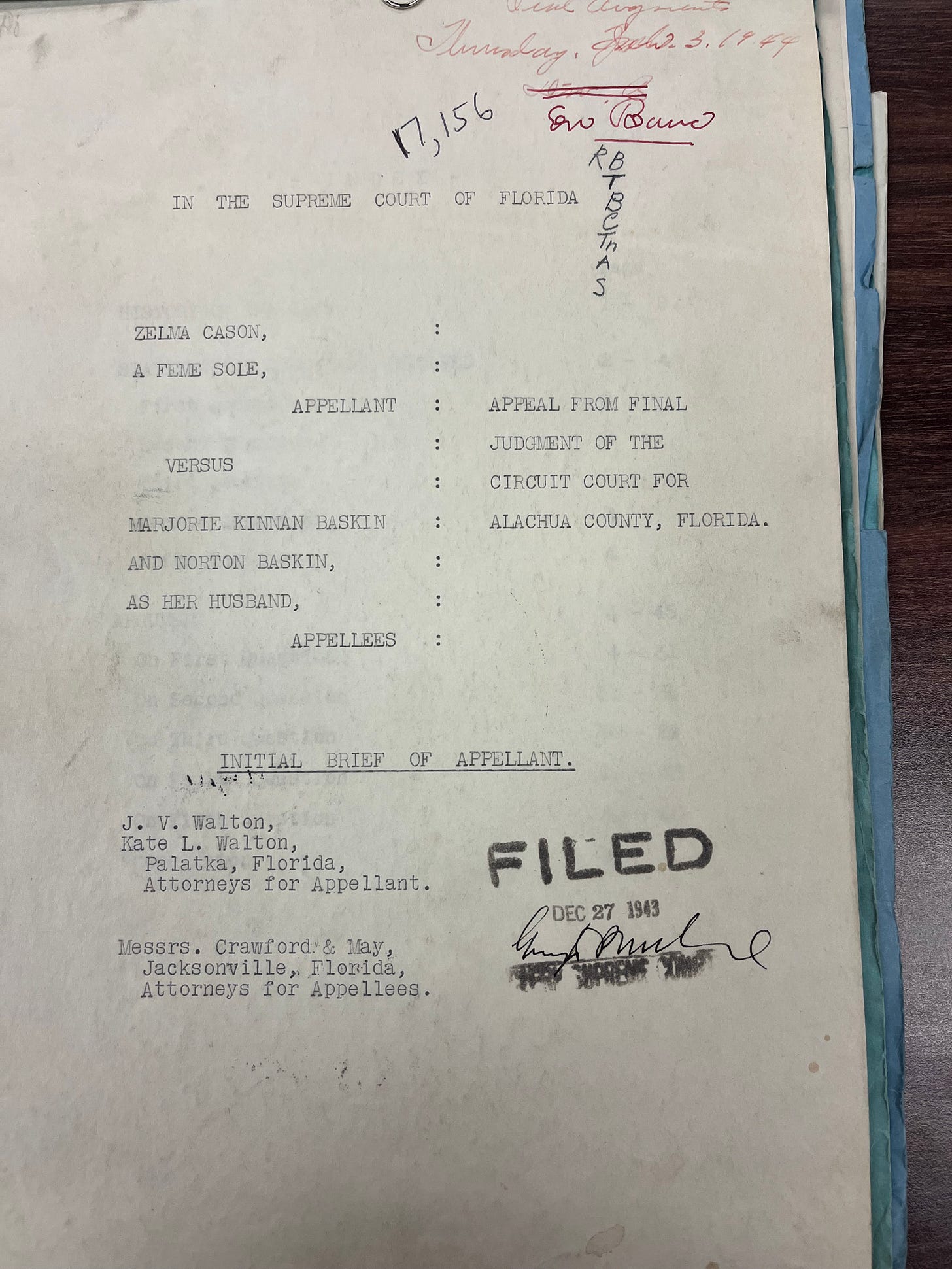

The official title of Zelma’s lawsuit, launched on January 8, 1943, reads as follows:

Zelma Cason, a feme sole

vs.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Norton Baskin, as her husband

The “feme sole” and “as her husband” addendum reflect a longstanding common law concept called “coverture,” which made a wife an extension of her husband in public and legal matters. The specifics are ably stated below in a Florida State University law review paper, written by Shawn M. Wilson in 1997.

At common law, a woman’s legal identity merged with that of her husband; she could not own property, enter into contracts, or receive credit as an individual. This condition, known as coverture, created a need for the doctrine of necessaries because a married woman was dependent upon her husband for maintenance and support. By prohibiting women from obtaining necessaries, the law forced women to look to the bounty of their husbands for food, shelter, clothing, and medical services.

Coverture was still in effect in Florida when Zelma Cason, an unmarried woman, filed her lawsuit against Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Baskin in February 1943.

But within months, in June 1943, the Florida Legislature ended coverture as a legal restriction for married women, who were given the right and/or obligation of acting as individuals in business and legal matters.

Far more than most women of the day, the combatants of the Cross Creek case had lived as “feme soles” long before the legal abolition of coverture made it official. But until the 1942 publication of Cross Creek, each pursued independent journeys to self-sovereignty without much interaction. Kate Walton went to law school and then into her father’s practice. Zelma Cason went to work through the New Deal.

Marjorie’s journey to fame and self-sovereignty is most well-known and iconic. You can read about it in a number of places. I recommend Ann McCutchan’s The Life She Wished to Live, an otherwise authoritative 2023 biography that, fortuitously for me, doesn’t spend much time on the Cross Creek case.

In very condensed form, Marjorie’s post-divorce feme sole journey went like this: after reasonable success with her early stories and novels, she hit huge in 1938 with The Yearling, a “boy book” that really wasn’t. She won the Pulitzer Prize. She sold movie rights for $30,000. She became genuinely famous and reasonably wealthy. Thus, Marjorie became Marjorie for the American reading public in 1938.

We’ll refer back to those journeys from time-to-time, particularly when they intersect with testimony or legal argument or narrative theme. But you’re reading a biography of the Cross Creek case – not of Kate Walton, Marjorie Rawlings, or Zelma Cason. So we won’t dwell long in the 1930s, despite its formative significance to each woman.

***

The 1943 repeal of coverture freed Marjorie’s new husband, Norton Baskin, from any technical liability for his wife’s behavior. The Florida Supreme Court, in its final ruling on the case, stated:

The husband was merely a formal party defendant, a formality later rendered unnecessary by the adoption of Chapter 21932, Laws of 1943, F.S.A. 708.08 to 708.10.

Jury instructions for the trial specifically directed that the jurors could not find Norton guilty. However, as I understand the “doctrine of necessaries” that remained in place, Norton would have remained on the hook for financing a verdict if Marjorie couldn’t pay.

But Marjorie could pay.

Marjorie’s official answer to lawsuit interrogatories said she made roughly $70,000 off Cross Creek between its 1942 publication and February 1, 1946. In a 1945 letter, she gave her lawyer Phil May a written accounting of her total book earnings:

Over the 12 years since my first book, (this is just between you and me) I estimate that roughly $200,000 was paid me, and after my modest living expenses over those twelve years, and the income tax, I have myself saved almost exactly $100,000, and while that seems like a great deal of money to me, it is not a high figure in relation to the sales of the books.

Marjorie also made $30,000 for the film rights of The Yearling. I’m not sure if she’s including that in her $200,000 figure. Adjusted for inflation to 2023 dollars, Marjorie’s $200,000-ish comes to more than $3 million over 12 years – for an average of $250,000 per year. But most of that came in just a few years after 1938’s publication of The Yearling and 1942’s publication of Cross Creek.

These cold figures help underscore the personal lethality of the lawsuit she faced. Marjorie had no author’s insurance. If she lost the $100,000 verdict Zelma demanded, she lost her savings and her hard won financial independence and mild wealth. She would lose herself in many of the ways most important to her.

Kate Walton was trying to take away Marjorie’s own self-sovereignty as punishment for her invasion of Zelma’s. It’s important to remember that from Marjorie’s point-of-view when considering the appropriate balance of invasion and punishment – and in judging Marjorie’s reaction to it.

What Marjorie would lose was existentially disproportionate to what she took from Zelma. But that’s the whole point of punitive damages.

***

Zelma, as a “feme sole,” had been earning her own money regularly since 1933, thanks to necessity and the first 100 days of FDR’s New Deal. Here is Zelma’s journey to independence, encapsulated in a trial exchange with J.V. Walton:

J.V.: Then other than this casual census taking at so much a head, the first time you were really employed, went to work for money, was in 1933?

Zelma: 1933

Q: Did you go to work then from choice?

A: Because I had to; to support my mother.

Q; You do it, and assist in supporting your mother; do you?

A: I support her and maintain the home.

Q: Now, what has been your employment – what was the position you took in 1933, of employment?

A: I ran a small ERA Nursery School first in Island Grove; I was with Mosquito Control under ERA; and after the nursery school was closed I became what is known as a “Case Aid” under ERA.

Q: What were the duties of a Case Aid?

A: Investigation and certification.

Q: Investigation under the direction of some …?

A: Supervisor and director.

Q: Were there many other persons employed as Case Aids, in doing that line of work?

A: There was. In this country there was about twelve at that time.

Q: After that, what did you do?

A: I went to work with the State Welfare Board.

Q: In what kind of a position?

A: Visitor.

Q: Just what is a visitor and what are the duties of a visitor?

A: To investigate, write a record, and certify.

Q: To what?

A: Old age assistance, aid to the blind, and aid to dependent children, and service cases.

Q: How long did that employment last?

A: Over a period of ten years.

Q: And you are in that work now?

A: I am.

Census records show Zelma made roughly $1,800 in 1940. If you call that an average salary for her, Zelma made about $21,000 over the same 12 years that saw Marjorie earn $200,000. At the time of the trial, Zelma’s yearly income had grown to $170 per month -- $2,040 per year.

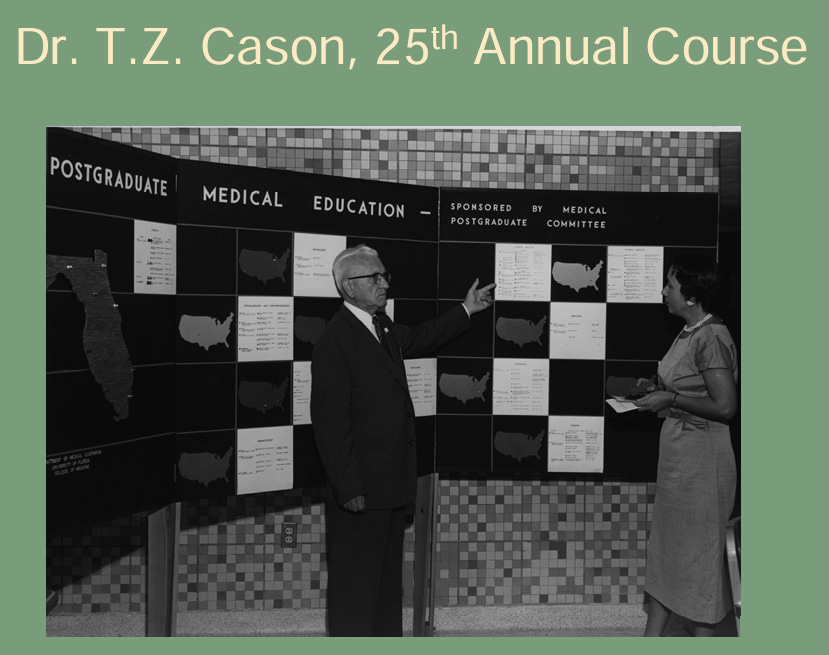

Zelma’s independence emerged from the need to care for her mother personally and financially. That need itself becomes almost shocking when one considers that Zelma’s brother, Dr. Turner Ziegler (T.Z.) Cason, was arguably the most influential and prominent physician in Florida from the 1920s to the 1950s.

This exchange between Zelma on cross examination by Phil May is, frankly, hard to believe:

Q: I believe you testified on your direct examination that you had to support your mother.

Zelma: I do now. That’s the reason I went to work.

Q: Does your brother, Dr. T.Z. Cason, of the Riverside Hospital, in Jacksonville, assist any in the support of your mother?

Zelma: He does not.

T.Z. Cason co-founded Riverside Hospital in Jacksonville in 1921, which would become the first hospital in Florida to perform X-rays, electrocardiograms, and blood chemistry test.

As elite Florida women with resources, Marjorie and Kate Walton both spent time in Riverside Hospital with ailments that became fundamental characters in the story of the case.

In Kate Walton’s case, Dr. Cason was so interested in her particular unknown condition, and showed it so often to medical trainees, that she threatened – apparently tongue-in-cheekly – to sue him for invasion of privacy, long before the Cross Creek case ever came to be. That’s how Kate came to connect with Zelma, through Dr. Cason, Marjorie came to believe. That story may be largely apocryphal; but Marjorie believed it enough to investigate it after she heard it from someone.

***

It makes sense that Dr. Cason would fixate on an unusual case for the benefit of students or trainees. There is little doubt he was the most consequential medical educator of his time.

He was also a genuine force for integration in medical training, long before the 1960s Civil Rights movement, as documented in a 2006 presentation by Sarah Vinson, with the University of Florida’s College of Medicine.

In 1933, the Florida Medical Association appointed a committee, with Cason as the chair, to organize a week-long graduate course for physicians.

In a letter to a Virginia doctor seeking advice on integrating the course, Dr. Cason describes the short course prior to integration:

“The first three years this course was held in conjunction with the University of Florida and held at Gainesville in university buildings. The question of offering some form of graduate education for Negroes was discussed but because of our affiliation with the University of Florida and the fact that it was held at the University precluded any attempt to invite the Negroes to attend this course. After four years affiliation we mutually severed our association and since we have been cooperating with the State Board of Health.”

In 1940, Dr. Cason invited black physicians to attend part of the week-long course for white physicians. Vinson writes:

[Dr. Cason] expressed “a personal desire to try this out.” He went on to say, “If it works successfully I am in hopes that the committee will next year approve inviting the Negroes to attend the Short Course as given the white physicians and on the same terms.”

The partial integration succeeded, leading to full integration of the course, under segregated social conditions, in 1941, just before the publication of Cross Creek and the emergence of Zelma’s lawsuit.

T.Z. Cason remained head of the Department of Medicine at the University of Florida Graduate School until the College of Medicine was founded in 1956. And he served as the FMA’s chair of the Postgraduate Education Committee for 27 years.

All of that makes his failure, refusal, or inability to help Zelma care for their mother jarring to read from 70 years in the future – especially if it meant no financial support. It’s the opposite of coverture, which did not apply to brothers and sisters.

But that did not stop Marjorie from imagining that Dr. Cason could play a coverture-adjacent role in the life of his sister. She unapologetically sought to use the eminent Dr. Cason to control Zelma at two of the most crucial moments of their relationship.

Marjorie’s meddling with Dr. Cason in her relationship with Zelma was the trigger for a friendship-ending 1931 post office parking lot confrontation, in which Zelma melted down on Marjorie. Marjorie acknowledged this in her “my dear foolish Zelma” letter from 1933, in which she wrote:

I wonder if it has ever occurred to you that the comment I made to your brother that made you so angry is a true one, and that for your own good you should stop and think about it instead of being furious at me? It was no tale-telling behind your back on my part — merely my answer to Turner’s remark that he couldn’t understand why Clara had it in for you so.

Your “vicious little tongue,” for which you “needed to be spanked” is your worst – your only — enemy.

Marjorie reiterated it at trial, during her testimony:

I remember I was very much disturbed, naturally, by her request or demand that I break my friendships and I remember that I asked her mother and her brother to use their influence with her, show her that she was being unreasonable in that request. My memory of it is that I saw them at separate times, but I could not be certain of that.

Moreover, T.Z. Cason, beyond his general institutional state prominence, had a profound personal impact on Marjorie Rawlings.

On June 17, 1938, Marjorie told her editor Max Perkins that Dr. T.Z. Cason likely saved her life by talking her out of a rather barbaric intestinal surgery with a 40 percent mortality rate. Note the bold:

Well I got out of a devil of a mess by the skin of my teeth. I can’t be positive of being through with it, but a reprieve is something. The three musketeers who are like brothers to me, got together and practically refused to allow me to go ahead with the operation without a corroborative diagnosis. I put up a fight, for the X-rays looked incontrovertible, and if I don’t make up my mind quickly and stick to a decision, I suffer too much in vacillating. But I gave in a the last minute and they took me to Jacksonville, where the head of a fine private hospital, also a friend, put me through everything again….

…It seems the mortality for that particular operation is 40%. Even if it is necessary, the Jacksonville man said there was no one in Florida competent to do it …

The Jacksonville doctor friend said the Tampa surgeon had made utterly inadequate preparations. The restricted diet should come first in my case, and in second place my blood should have been typed and two donors ready the moment the operation was done, as transfusions are invariably necessary. So with the mortality so high even when a top-notch man does it, I can see that the Tampa man was going at it blindly, and the Jacksonville man was probably right, when he dismissed me yesterday, saying, “If you’d done it, you’d have been cavorting with the angels just about now.”

Later, Marjorie will begin to suspect the same Dr. T.Z. Cason — who likely saved her life — of instigating the Cross Creek lawsuit through his influence over Zelma.

And she would actively seek to “blackmail” T.Z. Cason — who likely saved her life — into forcing Zelma, the “feme sole,” to drop her suit through some act of unofficial coverture.

***

In an earlier chapter, I noted that Peggy Whitman Prenshaw, a noted scholar of southern literature and an admirer of Marjorie, wrote this about her:

“… what Rawlings most deeply resented and found personally debilitating – and fought against all her life – was the powerlessness of the average woman, the powerlessness of even exceptional women in her society.”

I think many modern devotees of Marjorie want to believe this is true. But it’s just not supported by the record. Marjorie’s actual behavior as a writer, businesswoman, employer, and friend refutes this notion thoroughly.

Zora Neale Hurston knew – and considered Marjorie’s low-grade misogyny personally validating. Consider this from a 1948 letter, in which she half-suggested killing Zelma.

Please tell her that yes, the Baskins and I are very close and warm. I consider that a triumph because the justly celebrated Marjorie K.R. does not usually take to women. I could have saved all kinds of trouble if she had let me just plain kill that poor white trash that she took up so much time with …

We’ll come back to Zora and Marjorie and the power/admiration dynamic between them in a later chapter.

Consider also how Marjorie treated and talked about her maids, including the very much not average Idella Thompson Parker. Marjorie did not think of – or seek to protect – her “perfect maid” in a sisterly way, as we’ll also see later.

Sure, one could dismiss that as a function of race. But most of Marjorie’s intimate relationships with white women also imploded, or were toxic, or defined by a loyalty that ran in one direction. Marjorie found it quite easy to abandon loyal friends, of any sex or race, coldly at her whim.

And the way she wrote about women to men is quite often viciously sexualized and judgmental under the guise of disinterested objectivity.

In a letter to Max Perkins in May 1938, Marjorie wrote perhaps the most Marjorie thing ever, in part, about Dr. T.Z. Cason and their shared understanding of women. Note the part in bold:

I have been most unhappy about my seeming—perhaps actual—impertinence in commenting on your personal matters. My comment was really an impersonal and abstract thing. I see such a thing, aside from my interest in your mental welfare, from a detached and clinical viewpoint. I had never thought that I had any gift for understanding complex people, or civilized ones, but I have come to believe that I do have a certain clarity of insight into the relations between men and women.

I have a friend who is a leading Florida physician and head of a large private hospital, who goes in for the psychology of such relations, and he insists that some day I must write about the things I know along this line. The subject does not appeal to me, but perhaps it will before I am done.

He is writing a book on the subject, and is using an essay I read to a group of men, “Letter to a Lady,” which dealt with one phase of the thing i.e. the jealous, female-spider-like possessiveness of the inferior female who tries to absorb a superior male—and, nine times out of ten, succeeds. So please consider me in this respect a casual analyst, and not an intruder.

A more accurate version of Prenshaw’s quote would be:

What Marjorie Rawlings most deeply resented and found personally debilitating – and fought against all her life – was the powerlessness of the average Marjorie Rawlings.

The Waltons – particularly Kate Walton – worked hard in litigation to amplify that idea.

As an “exceptional” woman, they argued, a woman of wealth, fame, and possessed of the power of narration, Marjorie was all too happy to invade the privacy of an “average” woman – Zelma – that she considered “inferior.”

They had a good case on the wealth scoreboard: famous $200K-plus author to $21K-plus New Deal social worker gives off a David and Goliath vibe.

But portraying Zelma Cason as the archetype of an “average” woman was fundamentally bullshit, as virtually everyone in Alachua and Marion Counties knew.

Consider this cross-examination exchange about Cason family prominence:

Q: Was there any other family in Island Grove that was more prominent than the Cason’s?

Zelma: I would not say. I could not answer that at all.

Q: Isn’t it a fact, Miss Cason, that the Cason family were sort of leaders of the community of Island Grove?

[J.V. Walton objected to both of those questions; Judge Murphree overruled both objections.]

Zelma: I would not know.

Q: You lived in the community; didn’t you?

Zelma: I did, but there was a number of families there.

Q: Was there any other family -- ? How many families were there that had college students in the family?

Zelma: I could not answer that. I know of one, the Shaw’s. That is the only one I think of, but there was others.

Zelma didn’t come from an average family; she didn’t have an average education; she certainly didn’t project an average personality or influence on her surroundings. Her social worker salary couldn’t match Marjorie’s income, but it exceeded most of her neighbors, according to Census records.

Zelma had many rocks in her citizenship slingshot and did not fear to fire them at whatever Goliath she saw before her in her community. She was politically active, socially assertive, and professionally and personally connected. That’s all well-established through Zelma’s grudging answers to her cross-examination.

That doesn’t mean Marjorie didn’t invade Zelma’s privacy in the personal, intimate, painful quality of Marjorie’s sexualized description.

But it does suggest the much-loathed (by Kate Walton) trial Judge John Murphree did the plaintiffs a great favor with his pre-trial 1945 ruling that Zelma’s community prominence and many acts of public citizenship did not make her a “public personage.”

By underselling Zelma, a far-from-“average” feme sole, the judge Kate Walton would resent for her entire life kept their case alive at its birth.

***

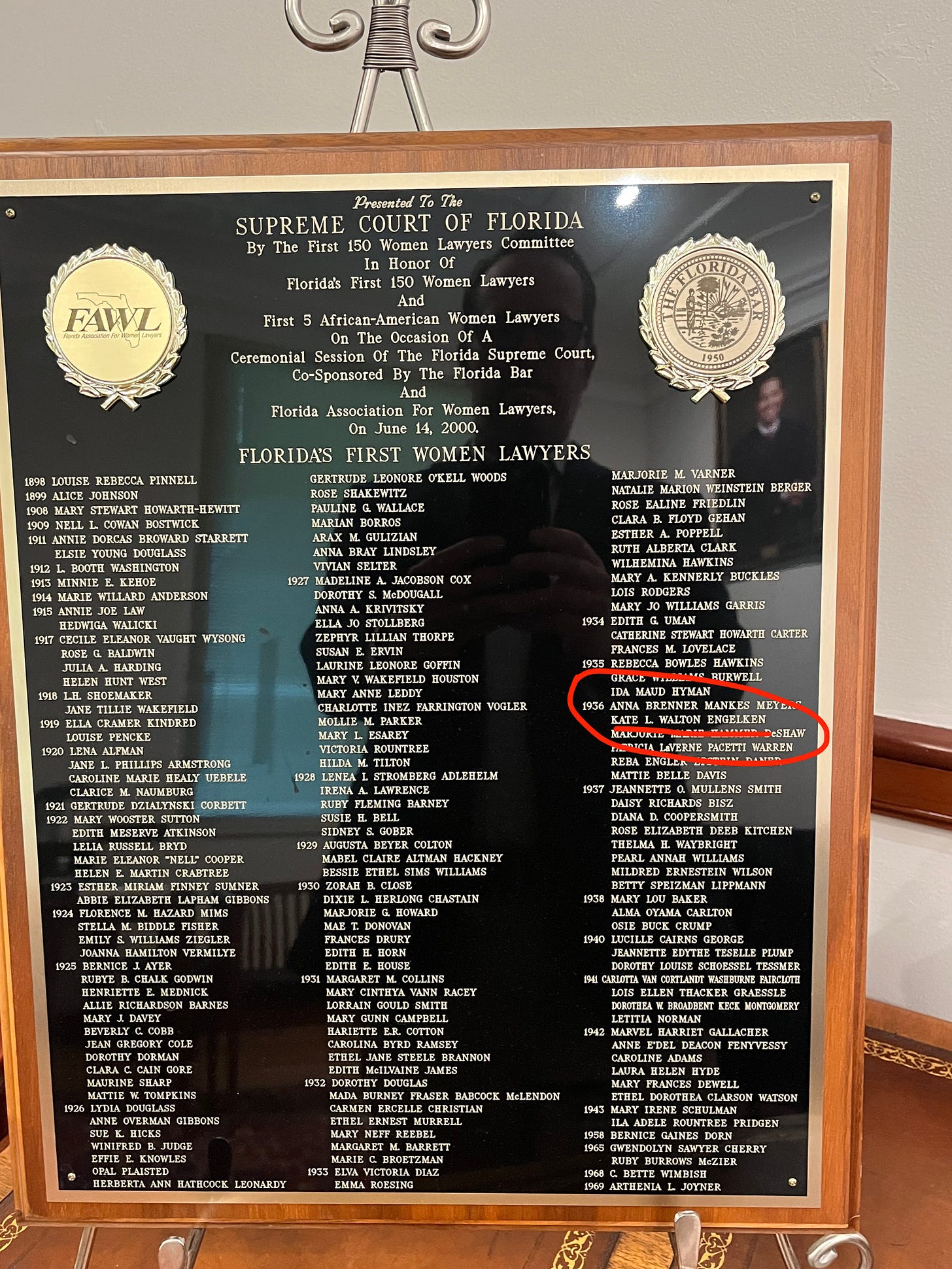

And speaking of far-from-average, on February 3rd, 1936, Kate Lee Walton joined 38 other students in graduating from the University of Florida in a “mid-year” ceremony.

Every other name – except two Marions – cited in the Tampa Tribune article announcing the commencement is clearly male. Kate earned and received a Legum Baccalaureus (LLB), which is an undergraduate legal degree that long entitled its recipient to practice law upon passing the Bar exam. Among the 39 UF graduated were about a dozen LLBs and one Juris Doctor. It’s not clear to me that Kate’s degree was any less strenuous than a JD. And later in life, when the LLB went away, she’d be awarded a JD under what seems like a grandfather clause.

About two weeks later, on February 19th, 1936, Kate Lee Walton became the 124th woman admitted to practice law in the state of Florida by its Board of Law Examiners.

In 2000, the Florida Bar published a booklet commemorating the first 150. I’ve reviewed the biographies of those pioneering women. I find that from among them all, Kate Walton:

Became the first true trial lawyer and adversarial legal advocate – as opposed to a non-adversarial specialist in areas like real estate or probate.

Performed more significant legal work than any Florida woman who came before her.

Inspired fear and respect from opposing counsel like no Florida woman before her.

You, the reader, should mistrust these conclusions I’ve formed about my beloved aunt because of how much I enjoy writing them. Indeed, here’s a fascinating off-key note from Kate’s bio in the Bar publication:

Interestingly, she received her best grades in such in such esoteric subjects as Roman law and admiralty, but received only average grades in areas in which she would excel in her practice – criminal law and trial practice.

But there is a massive difference between studying litigation and litigating; and perhaps we can learn an educational lesson here about how a curious, active, liberal arts mind can elevate into meaningful action the abstract study and short-term memorization of professional tenets.

Consider the words of prominent lawyer and family friend Harold Henderson, who saw all of Kate’s career coming before it ever happened. Here’s the full recommendation letter he wrote for Kate to the State Board of Law Examiners on January 21, 1936:

Dear sir:

It is with pleasure that I received your communication of the 20th inst. with reference to the application of Miss Kate L. Walton of Palatka to practice law in this State. It gives me infinitely more pleasure and satisfaction to give you this testimonial as to her character and fitness. It is unnecessary for me to comment on her character as it is blameless. She could hardly be otherwise being the daughter of Hon J.V. and Mrs. Sophie Walton. She possesses as good blood as there is anywhere.

I have perhaps as intimate a knowledge of the applicant as any other attorney (excepting her very able father) because of my intimate associations with her family. She is possessed of a most precocious intellect. She has a peculiarly analytical mind. Her reading has been more than general, and her knowledge of literature and of the classics is wide and extensive. My own son who was with her in law school has time and again told me how he marveled at her grasp of things and natural acuity. I believe she was the most precocious child I have ever known.

I am also going to take the liberty of observing that she has a personality and individuality which should take her far. She has the capacity to read character like a book, I never saw anyone who could detect a sham, or what her father and I commonly call a “four-flusher” quicker than she. She also possesses the rarest gift of humor. I personally know that she not only has mastered the fundamentals of the law but is conversant with its history, its traditions, and the reasons for it.

I would just as leave right now have her look up authorities and brief an important case for me as anyone.

I have never written a recommendation which has given me more pleasure that to write this humble testimonial of my appreciation of one of my most valued friends.

Henderson forwarded his recommendation letter to Kate with another letter addressed to her:

Now Katie, there is one peculiarity about writing recommendations in your behalf; -- that is to say, namely, to wit – one does not have to tell a lie. Not even a white one.

Now I want you to understand that if it were absolutely necessary I might even do this for you. Daniel Webster once shocked John C. Calhoun by admitting that under certain circumstances he might even perjure himself but he would do it like a gentleman. It would be only super-erogation for me to say that you have my good wishes for success, etc. I consider you grand success right now. In fact, you have always been a success.

I happened to be born with one of those temperaments which seem to keep me in perpetual litigation. I am apt to need a lawyer any time. Your father has ably performed this function in Florida and if I should get dissatisfied with him, it is a comfort to know I may employ you.

Everybody deserves somebody who believes in them in life like Harold Henderson believed in Kate Walton.

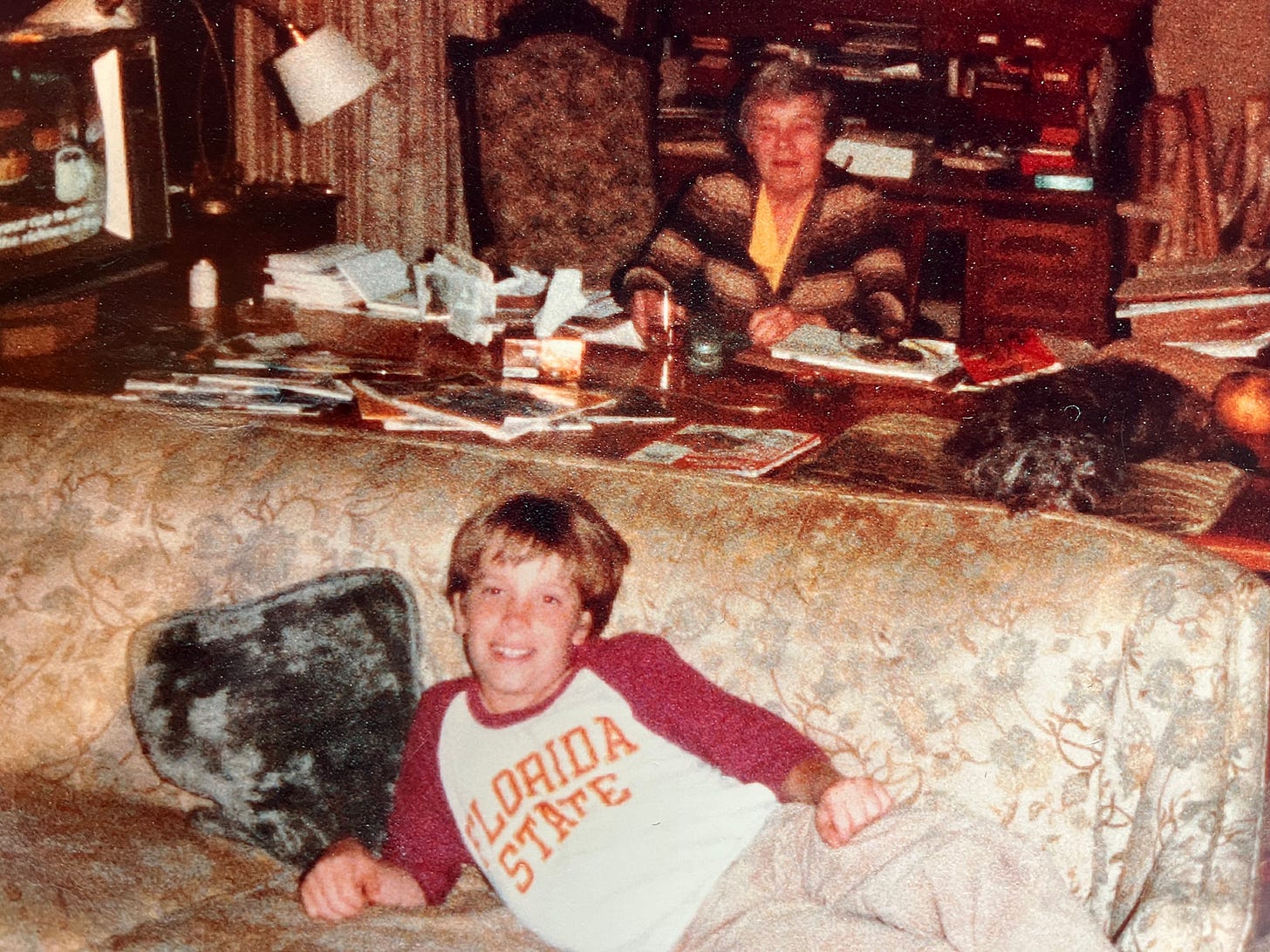

For me, for the first decade of my conscious life, that person was Kate Walton herself. She would tell me: “You’re the king of my heart.” As a little boy, she would kiss me at red lights to make them change to green while we waited in her ugly black AMC Pacer, which looked like a rolling tick.

And yet, for every loving word I can quote, every poem she recited to me, every memory I have of her home, for her desk at which I sit right now, I have virtually nothing in her own words to describe her own life as a feme sole and “grand success” before the start of World War II and the Cross Creek trial.

Instead, I have people talking about her or to her.

I have Kate Walton as images bounced off other people. These reflections say nothing about suitors or dates or parties or sex. They betray no intimate longings beyond driving an ambulance in wartime Europe.

But my grandmother Lois did say something very near the end of her life, in 2009, about the dynamic in the Walton household, where there were four daughters (Sophie, Kate, Mary, and Lois, in descending age) and no sons.

Mary thought that Sophie had kind of overshadowed Katie, and she loved Katie better than she loved Sophie. I thought Sophie was the most beautiful thing I ever saw in my life. She had a lot of evening dresses and all that kind of thing. And loved for mother to sew for her. She was pretty; she had a good figure. She was real popular and went to dances… Things were really very different then, the way that people did, chaperones and things like that.

I guess what I was trying to say was, Katie, I think always felt like Daddy had wanted her to be a boy.

I asked: Kate specifically? Or J.V. just wanted to have a boy?

Wanted to have a boy. But wanted to have her for a boy.

And I have a strange draft of an article or paper, which seems to have been written at the outset of World War II. It’s undated and untitled; and I can’t even be 100 percent certain that Kate Walton wrote it. But she almost certainly did – well before the Cross Creek case. I found it among her letters from Gray and Henderson and others. It sounds like her:

An individual is a lonely god who likes neither his loneliness nor the limitations imposed upon him by his physical structure in its relation to his environment. He can walk, he can run, but he’d like to travel faster; he can swim but he wants to fly – and he doesn’t like the loneliness. He is a little afraid of the peopled dark; a little awed by the vast immensity of the universe. Group living is the answer – first the couple; then the family; then the tribe or clan; then the city; then the state; then the nation; and now races and the union of nations and soon the world.

With each new complexity of grouping men gained in strength, in skills, in comfort. The ingenuity of one benefited all; the strength of all served the purposes of each; man learned to fly – what was impossible for one was easy for many who worked together. And the loneliness was pushed back a little.

We’re going to come back to this 6-page draft of a white paper – or whatever it was – on the balance of loneliness and sovereignty, of the individual and of the group. It’s spectacular – and challenging. Within it, Kate Walton, assuming it’s her, uses the term and concept “self-sovereignty” seemingly well before she adapted it to her written litigation in the invasion of privacy case.

For now, we should understand that a “feme sole” in the time of coverture was a distinct type of individual. And consider that Marjorie wrote this to surrogate daughter/protege Julia Scribner on Nov. 11, 1942.

And as you grow older, you will learn what is perhaps the greatest tragedy of human life that we are each of us unutterably lonely, and no friendship, no passion, no marriage, ever joined any one of us so completely and permanently to another human being that we can avoid that loneliness. The stupid never feel it to begin with period those of us cursed with the search for perfection do—and we never find it…

…I have had much more than my share of love in my life, more men who loved me than is really decent, and looking back on them it seems that if I could combine this from one, that from another, this from one way of life, something else from another way of life, I would have that completion that all of us who are sensitive long for. I have never found it. I am forced to the conclusion that we must accept the loneliness and learn to take from life what is good and right for each of us, and to be very grateful for moments of completion, and for anything that approximates it.

How does the meaning and character and feeling of self-sovereignty change if we make this edit to Kate’s opening sentences?

An individual is a lonely god who likes neither her loneliness nor the limitations imposed upon her by her physical structure in its relation to her environment. She can walk, she can run, but she’d like to travel faster; she can swim but she wants to fly – and she doesn’t like the loneliness.

See you next Sunday. Here again is last week.